This entry is from the lesson Teaching With Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca.

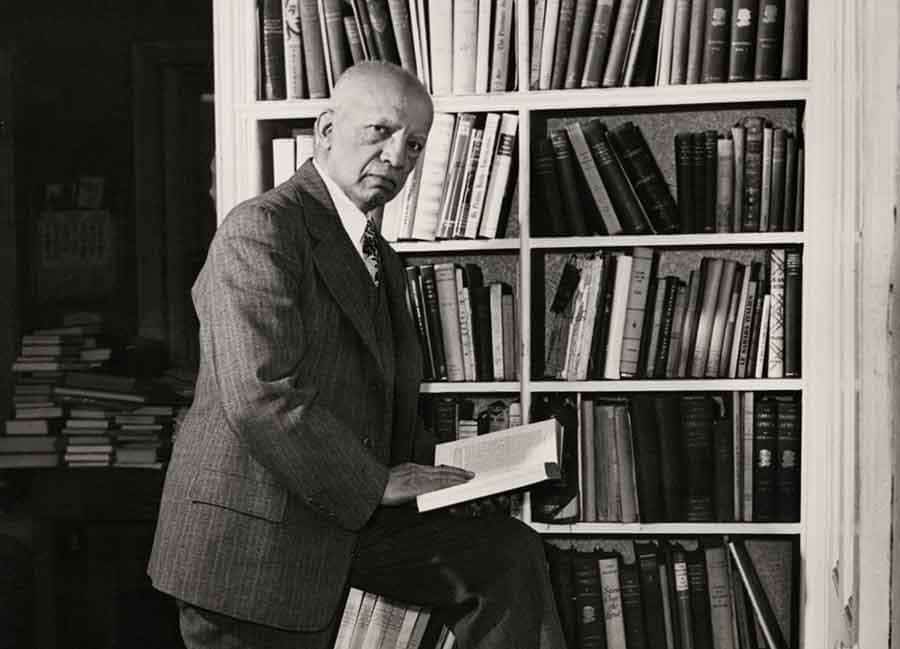

The arc of Mary McLeod Bethune’s life linked two moments of optimism for Black Americans. She was born in 1875, making her a child of Reconstruction, the nation’s first experiment in interracial democracy. Born Mary McLeod, she lived until 1955, long enough to see the dawn of the modern civil rights era.

Mary McLeod Bethune was one of the nation’s prominent educators and civil rights leaders. Political career includes appointments to National Youth Administration by President Roosevelt and delegate of the founding conference of the United Nations by President Truman. Established a school in Daytona Beach that eventually evolved into the Bethune-Cookman College. 1982 inductee to the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame. Source: Florida Memory, Photographic Collection

Bethune understood that she was an individual working at a political crossroads. She learned this approach from her mother and grandmother, women who were born enslaved and who had endured the exploitation of their production and their reproduction and had then survived to ensure their children thrived.

With the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, Bethune leapt to register Black women on her campus and in the surrounding community. In 1922, Bethune faced off against the Ku Klux Klan in defense of Black voting rights in Daytona, Florida. There are two versions of this story. Both begin with Daytona’s 1922 mayoral election. The candidates were at odds over whether to establish a local high school for Black students. Bethune openly organized Black voter turnout, urging support for the new school. Klan members aimed to stop her, threatening to destroy her school.

One version of the story goes that on election eve, hooded Klansmen marched onto campus while Bethune stood out in the open alone, arms folded in defiance. She had sequestered students in their dormitories, while faculty stood like sentries across the grounds. The mob briefly trespassed but then departed without leaving a mark on the campus or its leadership. The following morning, Bethune rose to get hundreds of Black Daytonians out to vote, and she remained a watchful presence there throughout the day.

Bethune herself told a slightly different version of the story, one in which she confronted the Klan flanked by students. The young people faced the trespassing terrorists and filled the air with the sound of their voices. They sang a hymn. In the aftermath, Bethune described “a band of women as far back as you could look” that accompanied her to the polls and “stood for hours and hours until we got our chance to cast our votes.” Both versions of this story reach the same conclusion. Black voters cast their ballots and ensured that Daytona’s first Black high school finally came into being.

Bethune dominated Black politics in Washington, but the wrangling there did not consume her. By 1943, her burgeoning internationalist vision built upon struggles against racism and sexism at home to embrace similar fights across the globe. Bethune linked the fight against anti-Black racism in the United States with anticolonial movements around the globe. She marched the National Council of Negro Women deep into wartime organizing and sat at the table when questions about the contours of postwar politics were debated. Bethune’s NCNW was among the groups that pressured the Allied powers to open the deliberations that led to the 1945 United Nations Conference on International Organization. Her message to U.S., British, and Soviet diplomats, as well as to her fellow activists, was singular: women of color must be at the center of any analysis of international human rights.

More on Mary McLeod Bethune

The statue of Mary McLeod Bethune makes me remember when my late uncle Junior always argued that MMB is the most important person in Black History.

While that is a matter of opinion, if we REALLY knew MMB, we’d see how compelling his argument was.

A thread. https://t.co/BnzOqJI4xs

— Michael Harriot (@michaelharriot) July 17, 2022

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn