The possibility of keeping justice alive in our time hinges on our response to the reality of a warming planet. We are going to have to become firefighters. — Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

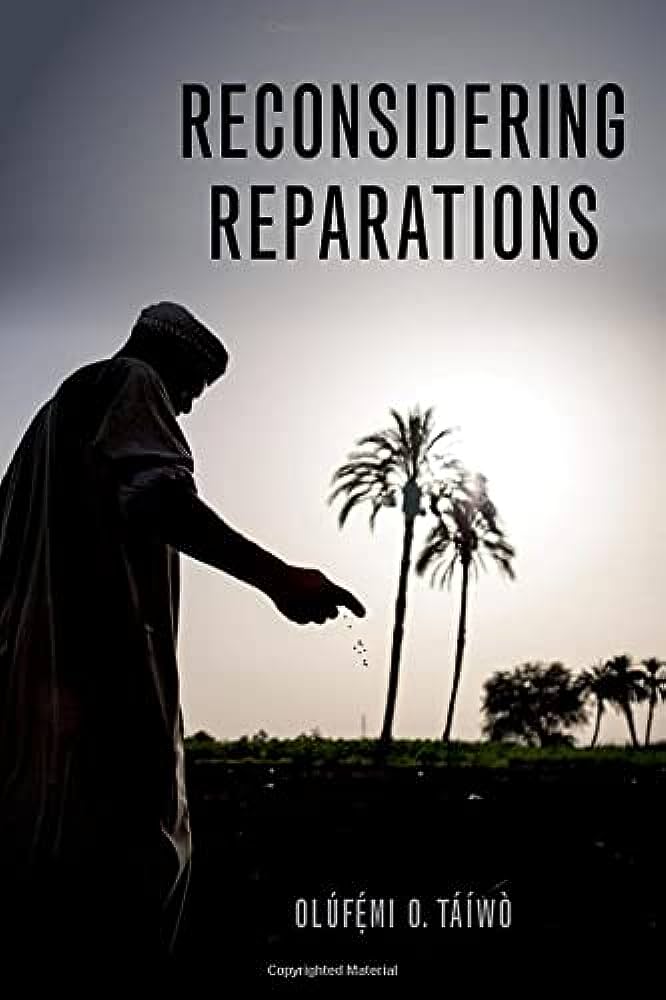

On Monday, May 6, 2024, philosophy professor Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò will discuss his book Reconsidering Reparations, which takes on Reparations and distributive justice with wide implications for views of justice, racism, the legacy of colonialism, and climate change policy.

Táíwò offers a clear, new case for Reparations as a “constructive,” future-oriented project: one that responds to the weight of history’s injustices with just distributions of benefits and burdens. Centuries ago, Táíwò explains, European powers engineered the systems through which advantages and disadvantages still flow. Colonialism and transatlantic slavery forged schemes of injustice on an unprecedented scale — a world order he calls “global racial empire.” The project of justice must meet the same scope.

Táíwò describes how the global racial empire took up industrialism and fossil fuel burning that now fuse Reparations with preventing runaway climate change. Environmental catastrophes echo past injuries. “If we don’t intervene powerfully,” he writes, climate change “will reverse the gains toward justice that our ancestors fought so bitterly for.” But this calculus discourages despair; it demands global resistance.

Reconsidering Reparations suggests policies, goals, and organizing strategies. And it leaves readers with brilliant advice: Act like an ancestor. Do what we can to shape the world we want our moral descendants to inherit, and have faith that they will continue the long struggle for justice.

Táíwò will be in conversation with Jesse Hagopian and Cierra Kaler-Jones. Jesse teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project. Cierra serves as the executive director of Rethinking Schools. Cierra is also on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project, and is a teacher, a dancer, a writer, and a researcher. She previously served as director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò is associate professor of philosophy at Georgetown University. Táíwò’s theoretical work draws liberally from the Black radical tradition, anti-colonial thought, German transcendental philosophy, contemporary philosophy of language, contemporary social science, and histories of activism and activist thinkers. He is the author of Elite Capture and Reconsidering Reparations.

These online classes with people’s historians are held at least once a month (generally on Mondays) at 4:00 pm PT / 7:00 pm ET for 90 minutes. In each session, the historian is interviewed by a teacher and breakout rooms allow participants to meet each other in small groups, discuss the content, and share teaching ideas. We designed the sessions for teachers and other school staff. Parents, students, and others are also welcome to participate.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn