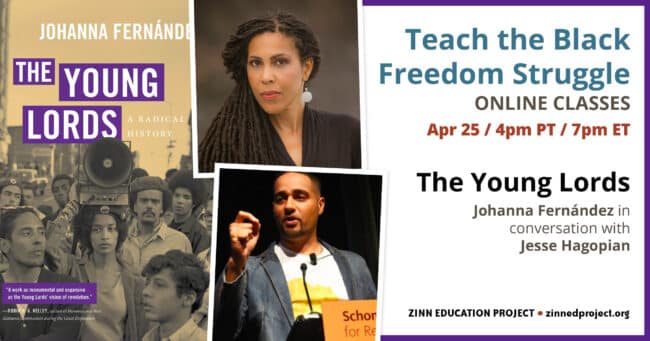

On April 25, the Zinn Education Project hosted historian Johanna Fernández in conversation with Jesse Hagopian about her book, The Young Lords: A Radical History.

Here are a few reactions from participants:

As a teacher, it’s important to me to present diverse perspectives and stories to my students that they can relate to individually. Being able to teach them about the Young Lords will make my students feel like the history books didn’t forget about them, too.

I am re-energized and I will continue to advocate and raise voices and experiences of Black and Brown lives in my daily life, especially in my graduate studies in a very white school.

Thank you for illuminating the multiple ways in which the Young Lords were groundbreaking in their vision and impact. As a Puerto Rican from the Bronx, I did not learn about the Young Lords in school, but heard about them in random family conversations. It is so important for young Latinxs to see ourselves as integral to the American story and as core leaders in the struggle to secure civil rights for all Americans.

As a 51-year-old Boricua, born and raised on the island, I am moved with pride as I learned about the Young Lords’ brilliance, humanity, and courage. I am also frustrated that I was never taught this in school, so I am looking forward to purchasing the book, and continuing learning and sharing. Thank you! !Pa’lante!

Thank you for teaching us so much about the Young Lords in a relatively short time. I will never forget what I’ve heard tonight about coalition, solidarity, and a long-term vision.

As a queer, Appalachian educator in Chicago, I greatly appreciate the connections revealed to me concerning the intersection of the Young Lords, Fred Hampton & the Young Patriots of Chicago, and the genesis of ACT UP’s actions thanks to the Young Lords!

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Hi, I am Jesse Hagopian. On behalf of the Zinn Education Project, we would like to welcome everyone here today to this class with Dr. Johanna Fernández. Some of you are joining us for the first time and some have participated since we launched this series. It is a gift to be able to share this time together and to be in virtual community all together.

The Zinn Education Project is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, and is hosting this session today as part of our Teaching for Black Lives Campaign. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that I bet a lot of you here have used — I know they got me through my first years, when I was thrown into an AP U.S. history class with no idea what I was doing. And I said, “Well, I’m just going to turn this into a Zinn Education [Project] history class instead.” I know so many of you all rely on these incredible resources. You can download them for free for middle and high school classrooms, from the Zinn Education Project website.

We have the good fortune to be with ASL interpretation today, provided by Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal. I hope I said that correctly. Before we begin this conversation, we would like to find out who’s in the room, and go through our plans for our time together. So, we want to post this quick poll to find out how many educators we have with us, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others in the room with us. If you have multiple roles, just pick your primary role. It’ll be great to see who’s all in the space with us today. So, those are coming in now, and we’ll get a chance to look at those in a second.

We also have members here from the Teaching for Black Lives study groups. We have like 100 different Teaching for Black Lives study groups across the country, with hundreds of members all over resisting the attack on anti-racist teaching that’s happening right now. I’m really proud of the work that everyone there is doing, it’s incredible. So, if you’re in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. Let’s check out the poll. It looks like we have 38% of us here today are K–12 educators; we have 2% students with us today, K–12 students; we have 20% teacher educators in the house; we have 4% historians; and we have 1% librarians. Welcome to everybody, so glad to have you all with us, able to spread these radical ideas around the country.

Throughout the session, we want to use the chat box — you can post questions, comments, resources, share ideas, and we’ll do a short evaluation at the very end. In about a week we’ll share the full recording of this event, and we want to share the resources that you all posted in the chat box or that members of the Zinn Education Project team posted. So, all that will be made available after this session. We also want to encourage you to tweet what you’re learning about today and invite others to learn about this special classroom that we have collaboratively constructed. Then, after about 25 minutes, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other. This part is really different from most of the webinars I attend, but it’s a great feature of this classroom that makes it interactive and allows you to process what you’ve been learning and share with and meet other educators and students and parents from around the country. So, we’ll have a short breakout session and then come back together to answer questions from those breakout sessions.

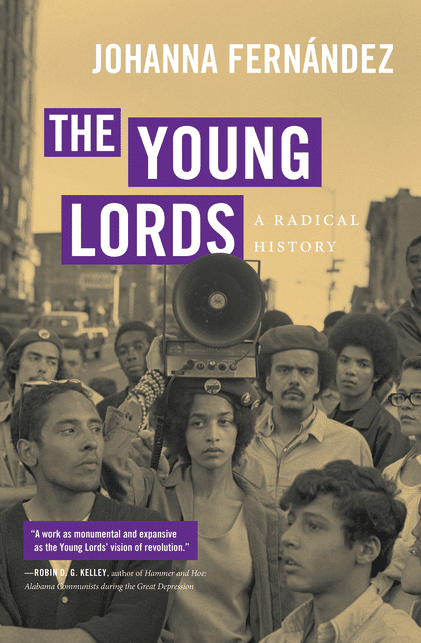

Now I am happy to welcome Johanna Fernández, Associate Professor of History at Baruch College of the City University of New York. She is the author of this incredible book, The Young Lords: A Radical History, and the editor of Writing on the Wall: Selected Prison Writings of Mumia Abu-Jamal, which, the first activism I ever did was around Mumia’s case. So welcome, Johanna, thank you so much for joining us in this conversation.

Johanna Fernández: Thank you so very much for the invitation. I’m so excited to be talking to teachers; it’s one of my favorite activities.

Hagopian: Well, we’re gonna have fun today, then. I just learned so much from reading your book. Thank you for writing it, and all the research you put into this. I’m really excited for this conversation because I think that the Young Lords transformation from a gang — or I think as you’ve better put it, a street organization — to a political organization — and then their contributions to the struggles for racial and social justice — is really one of the greatest stories of the social movements of the 1960s and 70s. And also one that is almost totally invisibilized in school. It rarely gets talked about. It’s also a story that’s essential for understanding the Black Freedom Struggle, which I don’t think I fully appreciated until I read your book because the Young Lords — while they were founded by Puerto Ricans, and the bulk of their membership were Puerto Rican and Latinx — it surprised me, I think, reading your book that they not only had a lot of Black Puerto Ricans, but they also had a significant percentage of their membership that were African American. Anyway, I looked through a bunch of my textbooks after I read your book to see what the textbooks are telling us to teach about the Young Lords, and of the several high school and middle school textbooks that I looked through, I didn’t find a single reference to the Young Lords. They were just shut out of the conversation altogether. So, I want to get into the origins of the Young Lords in a moment. But I was hoping you could begin by just giving us an overview of the scale and influence that they had, where they operated, and the scope of work that they took on in struggles for racial, economic, and social justice.

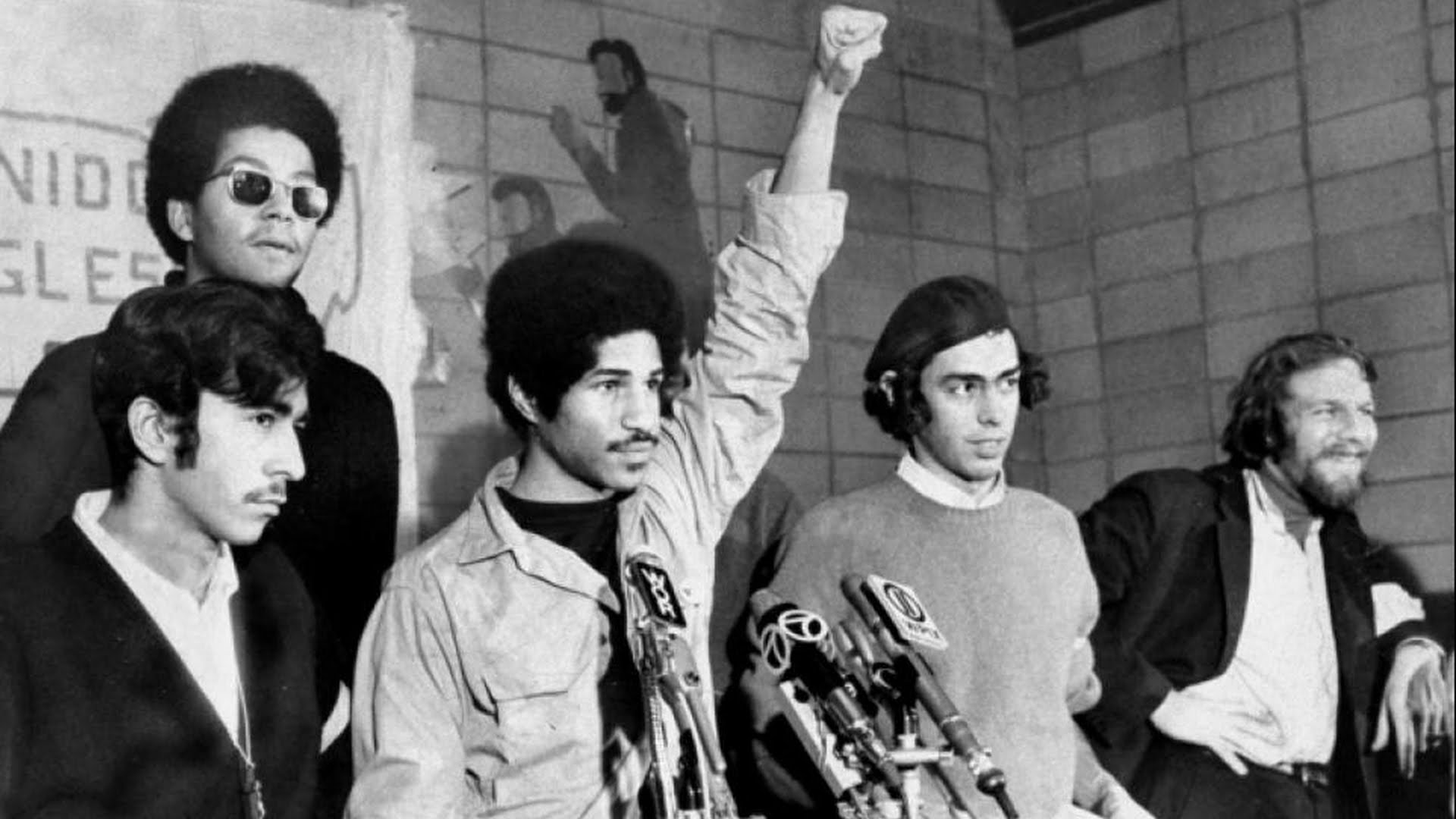

Fernández: So, the scale and influence of the Young Lords. The Young Lords were working class Puerto Rican youth, who organized in cities like New York, Chicago, Milwaukee, Philadelphia. At the height of their influence — in New York, at least — there were approximately 1,000 active members, and approximately 3,000 others who were friendly followers [who] believed that Puerto Rico should be freed. So their major contribution, I think, to the New Left was to expose the United States’ quiet colonization of the island of Puerto Rico. They were also socialists, who believed that we should build a society organized around human need, rather than profit.

And they were media Mavericks. They emerged at the height of radicalization, and at the height of this new technology, and leveraged it to influence the city beyond their numbers. And how did they do that? They paralyzed the city with garbage protests, for example. They were community based activists who actually asked the community, “What’s the problem here? Where should we focus?” So, the Young Lords’ activism was very accessible. They thought that they were going to be told, “We need to organize around police brutality, housing,” and the people in the community said, “the garbage.” There’s a fascinating reason why garbage is a problem, not just in East Harlem where they organized, but also across the country. Essentially, the 1950s produced an enormous amount of consumer garbage that our cities had not yet figured out how to dispose of. And of course, because of racism, communities of color got the short end of the stick in terms of services. So East Harlem had structural garbage that was dangerous. This was an environmental racist zone, much like other parts of the city. What the Young Lords did was they collected the garbage over the course of a series of Sundays, and parked it in the middle of the street to block traffic, for blocks and blocks and blocks on end. They did this repeatedly. They had press releases, demands to the city, and people got involved in this garbage jubilation — literally, the people started joining them in the streets. As a result of their activism, the city changed its model for disposing of garbage. The city met with the Young Lords on a number of occasions, although the Young Lords were not into negotiating with politicians. Essentially, what we got was a broader sense of the common good and an expansion of services for all — something that we don’t really associate with the Civil Rights or Black Power movements.

They occupied a church, as was said previously, because they believed that institutions in the community should address community problems and should be beholden to the community. This church in the middle of East Harlem was wealthy and was essentially not involved in any significant way in the problems of the community. This also happened in Chicago. In Chicago, the Young Lords took over a seminary. That was an epic struggle, because they actually got the Methodist Church to donate approximately half a million dollars for housing with dignity for poor people.

I’m going to end soon, because I know we have to get to other topics. But one of the on explored aspects of the 60s is that activists were paying attention to the lived environment and the ways in which the urban city — our neighborhoods, our schools — produce depression, essentially because they’re decrepit. The architecture is organized to alienate, literally, urban dwellers. So a group of predominantly Black American and Latino architects and their supporters started to reconceive the city as a more hospitable place where community could be forged. So the Young Lords, alongside architects in Chicago, created a plan for this liberated architectural housing zone for poor people.

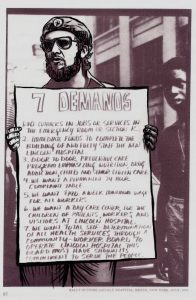

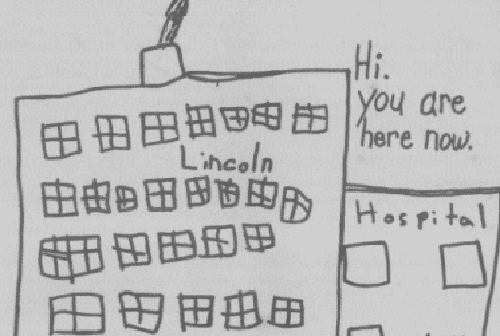

I can go on and on and on. They are responsible for drafting the first known “Patient Bill of Rights,” something that we take for granted and that we see everywhere in hospitals the world over. That document emerged out of a struggle around discrimination in health in our hospitals, and the poverty of care afforded to Black Americans and Puerto Ricans in the South Bronx.

Hagopian: Incredible stories and accomplishments that I just still feel bad that weren’t taught to me in school. I appreciate that. One of the things I was also reflecting on is something that you said around how they formed toward the end of the radicalisation [period of the 1960s], and how they benefited from learning from so many of the mistakes and the political development of the movement as well. So, that’s something I’m still just sitting with and reflecting on.

I was very fortunate to get to meet [José] “Cha Cha” Jimenez at the 50th anniversary celebration of the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party, thanks to my friend, Black Panther Party Seattle Captain Aaron Dixon, who brought him here and was just so thrilled to get to share that legacy with us. Cha Ch was one of the leaders who helped transform the Young Lords, of course, from a street organization into a political organization. I found your description of his early years, and his interaction with school, really fascinating. You wrote in the book, “At school, Cha Cha’s teachers, including many of the pastors, called him Joseph rather than José, a point he remembers with shame because he didn’t resist it.” And then, even before he got to school in the morning, he had to deal with white gangs that were terrorizing Puerto Rican kids on their way to school. Then you wrote about a critical moment in Cha Cha’s life coming in high school when he and his family were not invited to the school’s yearly graduation party. So, I was hoping you could just talk more about how Cha Cha’s early life — segregated housing and systemic racism in the schools — and how that shaped his consciousness in ways that would later politicize him and help him transform the Young Lords.

Fernández: Before I go to this question, the first chapter of my book is dedicated to Cha Cha Jimenez and his transformation.

Of course, in the context of this mass migration of Puerto Ricans from the island to cities like Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, a third of the people of the island of Puerto Rico were displaced after the United States’ industrialization project on the island. Operation Bootstrap didn’t actually absorb into the economy the farmers that it displaced, so it had an escape valve and that was the out migration of a third of the people of the island. This is epic to cities; this is a dismembering of a country, of an island, of a nation. And I tell that story, through Cha Cha Jimenez, and I focus on Cha Cha Jimenez because his story of transformation is not unlike that of Malcolm X’s transformation from petty criminal to epic civil rights leader.

But also, when we think about the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, we think of Ella Baker, we think of individuals, we think of Martin Luther King. I felt that in order to integrate the history of the Young Lords into the classroom we needed to understand individuals — who they were and how they were transformed, and why they decided to take the reins of history and give all to these movements. Cha Cha Jimenez is really one of my favorite Young Lords. He’s an incredible, incredible human being.

What’s the relationship between structural racism and the experience’s that Cha Cha had in Chicago, and the early radicalization that he experienced, which he probably wasn’t aware of as a political transformation? So, in thinking about this earlier, I thought, “Well, let’s take a step back. What’s going on in the United States, both domestically and globally? The United States after World War II — precisely at the moment of this mass migration of Puerto Ricans, but also Black Americans from countryside to city, Mexicans from Mexico, to the United States, Chicanos and Mexican Americans and Native Americans, from countryside to city.

This is also a moment when the United States is becoming hegemonic. It is becoming a world power, a superpower. And that’s going to have an impact not just on what’s going on globally, but what’s going on domestically. So, what happens domestically, economically, is that the United States becomes economically powerful. The 1950s are the golden age of American capitalism, and that capital really is organized around consumption, not industry. Previously, it had been organized around industry, the first birth of American capitalism in the late 19th century, but now it’s organized around consumerism. So, when we trickle this down to what impact does this have on the city, the city needs to be reorganized. Downtown areas are going to be taken over and the most coveted real estate is going to be bought, essentially by businesses. Prior to this period, downtown areas were very rickety, and poor people, working class people, lived in downtown areas, like in Chicago. And that was an area that was in fact close to the river. And at a moment when the American Empire is exploding, its major cities are going to have to reflect that growth and expansion. There’s an attempt to buy up all of this land that people of color and working class people live in. So, they begin to be displaced out of their living quarters to inhospitable neighborhoods. In Chicago, thousands and thousands of families were pushed out of that river front property up to the outskirts of neighborhoods populated by working class white ethnic groups — the Polish, the Germans, the Irish — in Chicago. And so Cha Cha’s radicalisation begins when he encounters terror on the part of white gangs, who are essentially playing out in the streets and in the playground what they’re hearing from their parents about the newcomers — that the newcomers are destroying our city, that they are undeserving of the resources and spaces of our city.

Puerto Ricans are super exploited, they’re at the bottom of the totem pole in terms of labor. They have the least paid jobs, they’re struggling, and they’re perceived because of race and ethnicity to be inferior. Cha Cha Jimenez realizes that he has to defend his people and his cohort against this white terror. So, the very organization of a counter gang in defense of people of color against white terror is itself a political endeavor, whether they realize it or not.

Then there’s the contradiction that Cha Cha Jimenez’s mother is very religious. She organizes in the Catholic Church, and the Catholic congregation is forced to organize its Sunday services in the basement of the church, not in the main nave, because the German congregation wouldn’t have it otherwise. Cha Cha resents his mother for not standing up, and then he hears the priest talk about Black Americans as niggers. And he is waiting to hear the other bomb drop, for him to talk about Puerto Ricans and Mexicans as spics. This is the place where justice is supposed to happen, equality — the church, where we give our hand to the poor. So, this is a big contradiction that begins to awaken him to the inequalities in society. And I can go on and on and on.

But there’s also his experience with the cops. He’s in a gang, gets involved in petty criminal activity, and begins to understand that the cops are not really there to address crime. They’re just going to pick up kids whether they were involved in criminal activity or not. Once you get picked up, you’re on their records, and you’re on the list to be picked up again, over and over and over again. And there’s an enormous amount of indignity that you suffer, day in and day out, in these exchanges with the police. So when he gets to prison, where he experiences a transformation, he starts hearing in prison on the radio the struggles of the Black Panther Party in Chicago. He thinks, “They’re fighting the cops. I know the cops, they’re dirty. Maybe we need to get together with the Black Panthers to fight for something larger than ourselves.”

Hagopian: Wasn’t he in jail when he learned that Martin Luther King had been assassinated?

Fernández: Yes, and that’s an incredible story. He happens to be in prison when Martin Luther King is assassinated. There are riots in Chicago and across the country, and there are roundups of people in the streets who are involved in the urban rebellions and who are not. Among them, migrants are rounded up. When I interviewed him, he said, “Yeah, these migrants were pulled in, and they were being abused. I was called to serve. I felt like I needed to serve my people for the first time. And I asked if I could translate, because these young migrants, they were not involved in any of this.” And this is something he’s telling me — this is something that happens periodically, you just have roundups of migrants. I understand that now, he says, but I wasn’t aware of that, then, that this is just something that happens cyclically, that the cops round up the migrants. So he started translating for these migrants, he started reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X, but also Where Do We Go From Here?, a book written by Martin Luther King in 1967, and Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. And here we see the beginning of that transformation. He’s trying to figure out that existential question, “Who am I, and what’s my relationship to my community? What’s my relationship to society and to this country? And why am I on the outside, and what am I going to do about it?”

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt, it’s a powerful story of his transformation. I just raised that because Aaron Dixon was also in prison when he found out that Martin Luther King was assassinated and decided when he got out he was going to join the Panthers and start the Seattle chapter. So I just thought that parallel was really powerful.

Fernández: Another understudied dimension of the Black Power movement: all of the prisoners who were radicalized and joined these organizations.

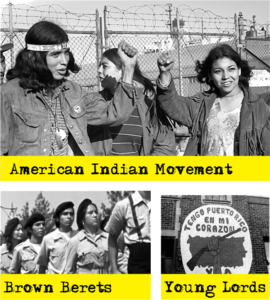

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. Well, I want to talk more about the politics of the Young Lords and what they stood for, because, you know, socialists discuss organizing the multiracial working class into a united movement, but this kind of unity has proved difficult to obtain in a country that was founded on structural racism, intentionally to divide the class by race. The Rainbow Coalition, I think, was really an incredible breakthrough for radicals and revolutionary socialists. You write, “Its mission was to build solidarity among poor and working class youth by promoting grassroots leadership among them in each of the city’s racially segregated communities, and tackling race antagonisms openly in the streets, at forums, and through collaboration across racial lines.” So, I’m hoping you can talk more about the politics of the Young Lords and the Rainbow Coalition.

Fernández: When I was doing research in Chicago and talking to Cha Cha and others, including members of the Black Panther Party in Chicago, what I learned is that Fred Hampton and other members of the Chicago Panthers had already initiated conversations with poor whites from Appalachia, migrants to Chicago. A year prior to the Rainbow Coalition’s emergence, but when the Young Lords emerge, for Fred Hampton, this becomes the lynchpin of the Rainbow Coalition. You can’t really have a coalition of two. You need a coalition of at least three or four, right? So when the Young Lords in Chicago emerge they actually reach out to the Black Panther Party and to Fred Hampton. The Young Lords are composed predominantly of Puerto Ricans and Mexicans in Chicago when this happens, that the Young Lords are a political entity or grappling or groping towards politics, Fred Hampton says it’s time to call for a Rainbow Coalition composed of the Black Panthers, who were Black Americans, poor whites from Appalachia in the [Young] Patriots [Organization], and Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in the Young Lords. It’s a coalition across racial and ethnic lines on the basis of shared class interests. And that’s it. Unfortunately that vision, that dream, was short lived because Fred Hampton was assassinated Latin American style in the streets of Chicago by the counterintelligence program of the FBI and the Chicago police, and that vision was not able to germinate. But the objective was to tackle racism in a real way, without canceling people, through difficult debate and discussion anchored around the history of exploitation and racial oppression in the United States, the history of slavery and its impact on labor and the working class in the United States. That’s where we got.

And when I interviewed the Young Lords, they said that Fred Hampton was not attempting to lord over the Young Lords, that he believed in the organic development of communities, and he wanted to engage in conversations. He was not prescribing an agenda, but he wanted to come in and participate in community conversations. He participated in a number of campaigns that the Young Lords launched — including a campaign against the killing of one of their own by a police officer in Chicago. At a moment when the New Left in Chicago was looking to protest that involved propaganda of the deed, targeting police departments and centers of power with bombs, Fred Hampton called together the Rainbow Coalition and decided to redirect the energies of protest in Chicago through the working class communities of the city — Puerto Rican, white working class, and Black American —to essentially educate the community about class, inequality, and race. So, it was a very grounded vision that he had, literally based on political education. Before we make common cause, or in the process of making common cause, we have to engage in serious political education in a country that has stripped its people of the history of the working class and the history of struggles against white supremacy.

Hagopian: It’s such an incredible example of uniting folks in a completely different vision for how humanity can exist together and use our resources to meet human needs. We’re so lucky to have that example to think about how to build on today. We are going to move to breakout rooms pretty soon here, where educators get to discuss what they heard here and how they might implement that in their classroom, and then come back and ask you more questions from the presentation. But I thought I’d do one more question before the break, and then I have a few more for you afterwards. But I wanted to get to this question about women’s liberation and the politics of the Young Lords, because you point out that the emergence of the New York group of the Young Lords coincided with the radicalization of the feminist movement and this shift in consciousness had an impact on the organization. You write that, quote, “The shift in consciousness, combined with the work of women of the Young Lords itself, made women’s oppression inescapable for these radicals.” And this situation, I think, helps to lead the Young Lords to make point number 10 in the 13 point program that they issued, which called for equality for women. I think this was a really important step, the formal commitment to women’s liberation. But you also write that, quote, “Yet in the thick of party life, women’s equality disappeared in the gap between word and deed.” So I was hoping you could just talk more about the important political leadership that women provided in the Young Lords and also more about their struggles against sexism, both in U.S. society and the world, but also inside the party.

Fernández: All right, so this is a fascinating topic. That point number 10 also reads, “machismo must be revolutionary.” So point number 10 says, “We believe in the liberation of women. We stand with our women, Puerto Rican women, and we believe that machismo must be revolutionary.” This is something that the women of the Young Lords co-signed in November 1969, when the [13] Point program was drafted. After the church occupation in New York City, the membership of the Young Lords increased exponentially, and more women joined the group, and it is at that time that women started meeting together to talk about the contradictions of party life. We’ve got this point, but we get to do the grunt work. We’re not allowed to be part of the Defense Ministry, we’re not taught karate and martial arts, as was the case with the men, and we’re essentially second class citizens. But also, what the hell is machismo, and what does it have to do with liberation of women? It’s antithetical to everything that we are fighting for. So, a struggle ensues within the organization led by people like Denise Oliver, who’s in fact a Black American, and she’s the first woman to join the formal leadership body of the organization, the Central Committee. Iris Morales is another major figure who’s challenging the men, not just on this issue of machismo and can it or can it not be revolutionary, but are we really equal in your eyes? How have you been socialized to objectifying women? And how have you been socialized to associate my sexuality as a woman with shame? These are the conversations that they’re having, that the women of the Young Lords are forcing onto the group. By the end of that struggle in the summer of 1970, point number 10 around women becomes point number five, and it reads “down with machismo and up with unequivocal women’s liberation.” The Young Lords then organizes both women’s and men’s caucuses to really challenge the ideology of gender inequality.

And it was not an easy struggle. Women say that the men of the Young Lords said, “Okay, you want to learn martial arts? Let’s go.” And they abused them, literally, as they were being trained physically. So it wasn’t an easy street, but they were able to gain ascendancy and respect in the organization. I’ll just end by saying something that I didn’t say earlier, and that is that the Young Lords are important for many reasons. Among them, that they help their generation understand how and why a third of a nation was displaced to the U.S. mainland. They gave their generation the language to understand U.S. imperialism in Puerto Rico, and they literally say, “We, the Young Lords, came to answer the question why? Why are our parents super exploited in the city? And why is being Puerto Rican associated with shame in this town? We came along to stand up and say that we’re not going to be pushed around, that we belong in the society, and we’re going to claim it.”

Hagopian: I would just like to begin by asking Dr. Fernández more about the politics of healthcare the Young Lords championed, and especially about this just breathtaking occupation that they did of Lincoln Hospital. I recently watched the documentary about that, and was just blown away by that. So, if you can start there.

Fernández: Yes. So, when I started doing research on the organization, it occurred to me that most of the organizing that both the Young Lords and the Black Panthers did was around issues of health. The Young Lords sanitation; both organizations literally created health clinics, and they were beholden to the breakfast programs. One of the questions I asked and answered in my book, which I don’t have time to answer [here] is why health? Why does health become so important in the 1960s? It has a lot to do with displacement, and the root shock of displacement, and the ways in which that affects our health and our communities combined with the transformation of legislation that makes health care available to people of color on a mass scale for the first time through Medicaid. Then they get to interact with these very conservative, unreconstructed health institutions, hospitals, where medical discrimination is legion, because literally they have not yet been civilized. So, the Young Lords did an enormous amount of work around lead poisoning, and they are credited by the Journal of Public Health for pressuring the city to pass anti-lead poisoning legislation. An incredible ruling.

The 1974 journal, one of the journals of that year, identifies the Young Lords in their activism. Where did this come from? Politically, they were hugely influenced by the Cuban revolution and the Cuban revolution’s determination to bring medical care into every sector of Cuban society, especially the poor. And they believed that medicine should be preventative. So they had a 10 point health program in which they identified the problems of health in urban centers as diseases of poverty. This is a term that they take from the Cubans, that many of the diseases, like pre-existing conditions — remember that term, pre-existing conditions — that seem to be racialized, then seem to suggest that people of color are biologically different from everyone else. This is what we heard during the whole COVID discussion, that no, that’s gobbledygook race ideology. The problem is that poor people, people of color, are disproportionately dealing with specific issues because of class and race. So what, are they? Diabetes.

Fred Hampton, in fact, did an enormous amount of work that people don’t know about around the food we eat, and the food that is not accessible to urban communities, healthy foods. I learned this from one of the Young Lords I interviewed who said he was one of the first people to come in and talk about these food deserts in our communities, and the impact they have on our health — high blood pressure, mortality rates among Black women and Latina women when they’re giving birth. They’re talking about all of these things and they’re saying, “These are problems of poverty and medical discrimination. They’re not a problem of biology.”

So, when the COVID nightmare was happening, I thought that the Young Lords would have a much better handle on the situation and explanation of pre-existing conditions than our government. Another thing they identified was horrific working conditions. If you’re working on the front lines, you’re getting paid very little and your body is being driven to the edge. You’re going to have a health crisis by your job. If your body’s being driven to the edge as these workers were delivering food to us at every second, you’re going to have a health crisis. So, they believed that the country could afford to reorganize health care by literally creating door-to-door medical care, by creating health captains in neighborhoods and communities, and by educating people in high school and in college, in the health industries. They actually critique the fact that the medical schools in the United States only admit a certain number of doctors, that they keep the number of medical professionals low for particular reasons. So, they had a really sophisticated analysis of healthcare for profit at the expense of the human needs, and they argued that the issue of health is important because it connects us to our common humanity. And it does so because it brings us together when we’re most vulnerable and more open to common sense. Our hearts are open because we’re in touch with our mortality.

So, they occupy Lincoln Hospital in order to dramatize the horrific conditions under which Black Americans and Puerto Ricans are being given care in this hospital. The Bronx, the South Bronx, is an industrial wasteland. Essentially, this is the beginning of deindustrialization and the South Bronx is being de-industrialized. It has the highest heroin addiction in the country, a mortality rate 50% higher than the rest of the country, and the hospital is a hospital that was built in a different epoch and literally looks and feels like an insane asylum. They think that this is unacceptable in the wealthiest city in the country, and they hold a press conference to expose these contradictions. And their actions lead to the creation of the new hospital building — the construction that was promised ten years earlier — and to the creation of the first drug addiction center that uses acupuncture in the treatment of heroin addiction. I can go on and on and on. But this is literally an epic story. It’s an epic story. And it’s there that they draft the “Patient Bill of Rights.”

Hagopian: It is an epic story. Everyone should read the chapter about it in here, [and] watch the film Takeover.

Fernández: By the way, they’re working with workers. They’re establishing a coalition among workers, low wage workers in the hospital. Hospitals are infamous — were infamous before unionization — for low wage jobs. They’re working with medical staff, and doctors, and people in the community, to pull these campaigns off. And what they do to occupy is that they literally all crammed into an apartment on the Upper West Side the night before the takeover. In the morning, they crammed people into a U-Haul, over one hundred people into a U-Haul, and they get to the hospital and secure all of the windows and doors and proceed to operate the hospital in the interest of the people.

Hagopian: Amazing. I love what you said about how they included the workers. One of their demands, I believe, was for higher wages for the hospital staff, because they knew that would contribute to better health care as well. But also because the workers deserved to be paid more. I think during the sanitation protests that they had burning garbage, even though some of the predominantly white garbage workers were refusing to service Puerto Rican neighborhoods, they were calling for higher wages for the sanitation workers as well to try to build solidarity with them in a united class-based struggle. Is that right?

Fernández: That’s absolutely right. You read the book, and noted a lot of detail in the book. That’s incredible. These were very, very young people who really understood the meaning of solidarity — that yes, you might think that I’m your enemy, but we’re part of the same class, and it is in our interest to stand together. So, even though I’m experiencing racism from Irish garbagemen of New York, I understand that you deserve a better wage, and I stand in solidarity with you. I’m making it part of my day, their demands for the city to increase the wages of the sanitation union in New York City.

Hagopian: We have so many questions from participants I want to get to now. One of them was about the Young Lords Rainbow Coalition with the Black Panther Party and other groups. Someone asked, “How successful was the relationship between the Black Panthers and the Young Lords to strengthen the racial justice movement?” I think part of that question also links to COINTELPRO, and also getting into the attack on what a threat the Rainbow Coalition was to the state and their repression.

Fernández: Oh, absolutely. I mean, that’s a complex question. The Young Lords and the Black Panthers were sister-sibling organizations. This was the height of radicalization. People believed that the revolution was upon us and that the only way to win was through solidarity, and racialized people in the United States who had experienced white supremacy should come together and fight for a better world. The Young Lords literally created the Puerto Rican counterpart of the Black Panther Party. There’s no better respect than imitation, literally. So, these organizations were profoundly connected. In New York City, when the Black Panther Party dissolved, its members joined the Young Lords. That’s what we’re talking about. Yeah, we are one. We’ve been divided. You know, we talk about divisions between Black people and white people, and white people and people of color, but there’s a lot of divisions among people of color, and between Black Americans and Latinos, and they fought to expose those divisions and fight against them in our communities.

I haven’t really talked about race, but the majority of Young Lords were Afro Latinos. So, part of why the Young Lords are important is because they literally theorized how racism emerges differently in Latin America under Spanish rule than it does in North America under British rule. This is something that’s sexy today in the university — like race in Latin America is a sexy thing — and the Young Lords decided to address racism, something that was within the Puerto Rican community and among Latinos, anti-Black racism was relegated to hushed whispers — they decided to bring that into the open and challenge it in the public sphere.

Hagopian: That’s wonderful. There was another question, somebody just wanted to know the difference between the Rainbow Coalition, the second iteration of it with Jesse Jackson, and the original Rainbow Coalition.

Fernández: Before I go there, to round that story up that I started, because the Young Lords were actually addressing anti-Black racism, they attracted Black American members. Thirty percent of the organization is composed of Black Americans who are not Latino. And another like 8% of the organization is composed of non-Puerto Rican Latinos. We have here one of the most profoundly multi-ethnic organizations in the history of the United States.

There is no relationship between the Rainbow Coalition that Fred Hampton created and Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition. The only problem is that Jesse Jackson did not credit Fred Hampton for coming up with the Rainbow Coalition, and he did not present to the world Fred Hampton’s vision. No class-based fighting coalition.

Hagopian: Someone just had a question about the name of the seminary in Chicago that the Young Lords took over, the McCormick Seminary.

Fernández: So, the McCormick Seminary in Chicago was the seminary that they occupied.

Hagopian: Somebody else wanted to know about the secret memo that was circulated from high school principals in Chicago?

Fernández: In New York. So, part of what I wanted to do in the second chapter was show how a generation of young people of color were radicalized unknowingly in the schools, in the streets, and in other institutions of the city. Because I interviewed the Young Lords, and they kept on referring to their experiences in the schools, and the racial discrimination they experienced at the hands of their teachers, and how that raised questions for them about who they were and what it meant to be Puerto Rican, and why was Black such a bad thing. And part of that history is a history of uprising against all of this by young people in the schools, and these uprisings which are led in the main by young people of color, because the demographic character of the schools change for the first time in the city. Now schools, after like 1966, both in Chicago and in New York, are majority people of color. Prior to that, they were majority white students, but because of the demographic transformation of the city, now the school population is predominantly Black American and Puerto Rican, who are up in arms and rebelling and taking a stand. The administration has to figure out a way of bringing this rebellion to heel, literally. And there’s an enormous amount of racism, the undertone of racism in these documents, that these kids are barbaric, and that they do not understand the meaning of free speech, and allowing all sides to have a word. They don’t understand the political institutions of our country, and their rebellions are too violent, militant, and we are not going to accept a protest on their terms. Literally, that’s what the secret memo says, and the secret memo is essentially a green light to principles to go hard on repression, to do whatever it takes to to tamper down repression. That’s going to come through suspensions, but also through the introduction, for the first time in New York City, of security guards in the schools.

Hagopian: That’s a whole important history to understand too, how our schools got militarized. Well, we have so many questions that have come in. We have had more questions tonight than any other session, for sure. This is incredible. I’m really sorry, we’re not going to have time to get to them all. I want to ask one last one, and I also want to urge people to stay on and fill out the evaluation form before you drop off. So please, wait till the end here.

But for our last question, somebody was curious to know about what the Young Lords members and key leaders did in their lives and careers after the organization stopped being active. Then, I think connected to that, was another question that somebody asked that was about the legacy of the Young Lords and how the work of the Young Lords continues to influence and impact generations beyond their time, and how the struggle continues. I know just from the Supreme Court’s recent ruling that Puerto Ricans aren’t eligible for Social Security benefits or other welfare benefits. We see that there’s an urgent need to continue much of the work that the Young Lords took up.

Fernández: Yeah, they’re U.S. citizens of empire essentially. That means that they’re not citizens. So the Young Lords emerge between two epochs. If you look at the activism of the Young Lords, their health advocacy and their very militant, colorful, bold campaigns, it reminds us a lot of the work that ACT UP [AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power] did around the AIDS crisis. The Young Lords were in many ways through their activism tapping into the ethos and style of protest to come.

You asked a lot of questions there and I don’t remember them. Today, activists in Puerto Rico, interestingly enough, who have been organizing post-[Hurricane] Maria have been creating these wellness programs and these communal kitchens in honor of the Young Lords, or remembering the activism of the Young Lords. So, the Young Lords and their activism is intoxicating. There’s something, again, very accessible, very human, very smart and strategic about their work. They combined local action that was strategic, that attempted to identify a problem. In many ways, they targeted all the institutions of power — the church, the hospital, the police department — they occupied a police department in Chicago, the Young Lords. So, these are big institutions that define our lives day to day, and they wanted to make these institutions reflect the aspirations and the needs of working people of color.

Hagopian: I think you nailed it, just the legacy.

Fernández: Just to finish that there — so they engaged in local action that was strategic, that actually got a win or a lose. We’ve kind of lost track of organizing that actually has a logic, that goes beyond an episodic march or two, and that tries to win something that involves other people. But they also had a long term goal: They had a vision of a completely new society. That’s right. And they had a critique of capitalism. They had a critique of racism and its origins. So, what it means to be radical is to address root causes, and the Young Lords address root causes, but they were anchored in the community. As were the Black Panthers by the way. The Black Panthers, unfortunately, had to confront a homicidal campaign against them by COINTELPRO. Dozens of Black Panthers were killed in the streets by police. So, their activism was influenced clearly by this repressive assault on the part of the state.

Hagopian: Thank you so much for all that.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

“What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should” by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian (Zinn Education Project, If We Knew Our History) “Why We Should Teach About the FBI’s War on the Civil Rights Movement” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Zinn Education Project, If We Knew Our History) |

Books

|

In addition to Johanna Fernández’s The Young Lords: A Radical History and the Social Justice Books Puerto Rico book list, the following books and booklists were referenced: Children and Young Adults The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano by Sonia Manzano (Scholastic Press) Vicki and A Summer of Change! ¡Vicki y un verano de cambio! by Raquel M. Ortiz and Iris Morales Adults Harvest of Empire: A History of Latinos in America by Juan Gonzales (Penguin Group) The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation by Darrel Wanzer-Serrano (Temple University Press) Palante: Young Lords Party by the Young Lords Party (Haymarket Books) Through the Eyes of Rebel Women: The Young Lords, 1969-1976 by Iris Morales (Red Sugarcane Press) The Young Lords: A Reader edited by Darrel Enck-Wanzer (New York University Press) We Took the Streets: Fighting for Latino Rights with the Young Lords by Miguel Melendez (Rutgers University Press) |

Articles and Reports

This Day in History

|

Sept. 23, 1968: Young Lords Founded July 1, 1970: The Lincoln Pediatric Collective Forms to Serve Bronx Community July 14, 1970: Young Lords Occupy Lincoln Hospital |

Films

|

Dope is Death (film and podcast, 2020) (watch on YouTube) The First Rainbow Coalition (2019) Palante, Siempre Palante! (1996) (corresponding Youth Outreach Toolkit) Takeover (2021) (watch on YouTube) |

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I enjoyed learning about the post WWII connections/intersections between Operation Bootstrap, federal laws/policies encouraging the establishment of corporate footholds in Puerto Rico, the impact on agricultural workers that were not absorbed into the new industrial jobs, and the related policy push to get unemployed Puerto Ricans to leave the island. I found that information helped to more fully explain the wave of migration of Puerto Ricans in the 1950s-70s, but also the capitalist and geopolitical imperial policies impacting Puerto Rico and the diaspora.

I also enjoyed the explanation of the growth of consumerism in the 1950s as an underlying cause of the neglect of sanitation services to Puerto Rican communities and the strategy to confront that neglect with the garbage protests.

I found the information to be a valuable reminder of the anti-colonial and anti-imperial centering of the Young Lords vision, and that that was a core focus that helped build bridges of solidarity between racial, ethnic, and poor/working class activists.

The significance of representation and mutual respect for people of different nationalities.

The most important thing I learned was that on a very deep level the Young Lords and Black Panthers were very conscious of what their communities’ needs were and how to best respond to those needs.

I appreciated Dr. Fernández’s early comment about the Young Lords’ unique approach in their accessible activism, asking community members what they needed and actually acting on community needs. Her point on the deep understanding that the Young Lords had of their living environment (the church, school, hospital, etc.), is all the more relevant today when environments can continue to be an oppressor.

How women pushed the Young Lords to embrace more radical positions on women’s issues, dropping the “revolutionary machismo” in the 13-Point Program to replace it with “down with machismo.”

What will you do with what you learned?

I want to encourage teachers at my school to have students study the Young Lords through access points like The Takeover and The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano.

My students will learn to make connections between marginalized communities and the importance of working in solidarity.

Besides equipping my students with the skills to burn down the system, I will continue to make connections between their struggle and the struggles of “los de mas.” I also learned or reaffirmed that the “answer” is more action-oriented learning! It’s not enough to just learn this history, this next generation needs to be able to DO something with it.

I will teach how much has been and can be accomplished through multiracial coalitions and strategic community organizing.

I have a better understanding of the Young Lords to share with students, and more importantly, incorporate the concept of coalition-building as a front and center tactic that is universal to successful movements.

I plan to continue to teach the truth about the Young Lords using the new resources I learned about and the information I gained from this session with Dr. Johanna Fernández. In my class, we read aloud the book The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano by Sonia Manzano. We teach about the Young Lords by visiting The Museum of the City of New York’s exhibit on the Young Lords (except we did not visit this year because of the pandemic). I have been looking for resources that I could use with and modify for my fifth grade ICT class. I took notes from Dr. Fernández today. I plan to buy her book and look into the resources shared by the participants in the chat. This was very enlightening!!

Presenters

Johanna Fernández is associate professor of History at Baruch College of the City University of New York. She is the author of The Young Lords: A Radical History and the editor of Writing on the Wall: Selected Prison Writings of Mumia Abu-Jamal. With Mumia Abu-Jamal, she co-edited a special issue of the journal Socialism and Democracy, titled The Roots of Mass Incarceration in the U.S.: Locking Up Black Dissidents and Punishing the Poor.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn