The great writer, historian, activist, and critic, Eduardo Galeano, passed away on April 13, 2015.

His work was a gift to every teacher who hopes to make sense of this “upside down world” with students.

To explore Galeano’s legacy, we recommend his interviews on Democracy Now!, “The Debt Owed to Eduardo Galeano” by Dave Zirin, and all of Galeano’s books, including The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, Memory of Fire, Soccer in Sun and Shadow, Upside Down, The Book of Embraces, We Say No, and Children of the Days.

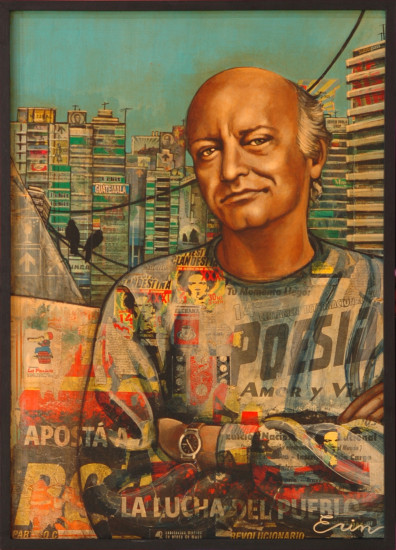

We share with you this beautiful mixed media collage and acrylic portrait of Galeano by activist artist Erin Currier. Currier gave us permission to post the image, adding that she was “deeply honored to have the portrait posted on the Zinn Education Project website. Galeano was one of my favorite authors. His books directly inspired many of my works.”

Remembering Eduardo Galeano

Democracy Now!, April 14, 2015

AMY GOODMAN: The writer John Berger said of Eduardo Galeano,

To publish Eduardo Galeano is to publish the enemy: the enemy of lies, indifference, above all of forgetfulness. Thanks to him, our crimes will be remembered. His tenderness is devastating, his truthfulness furious.

This is Eduardo Galeano reading from Children of the Days: A Calendar of Human History.

March 9, The Day Mexico Invaded the United States:

On this early morning in 1916, Pancho Villa crossed the border with his horsemen, set fire to the city of Columbus, killed several soldiers, nabbed a few horses and guns, and the following day was back in Mexico to tell the tale.

This lightning incursion is the only invasion the United States has suffered since its wars to break free from England. There was an English invasion in 1812, I think, but it was not a real invasion, just a chapter of a long history of fighting for independence. But this one was real last one, the Pancho Villa invasion. So, this was the only — the only invasion.

In contrast, the United States has invaded practically every country in the entire world.

Since 1947 its Department of War [changed the name,] has being called the Department of Defense, and its war budget [is now called] the defense budget.

The names are an enigma as comparable with the Holy Trinity.

Continue reading on Democracy Now!

From the Preface to the first book in Galeano’s trilogy, Memory of Fire:

I was a wretched history student. History classes were like visits to the waxworks or the Region of the Dead. The past was lifeless, hollow, dumb. They taught us about the past so that we should resign ourselves with drained consciences to the present: not to make history, which was already made, but to accept it. Poor History had stopped breathing: betrayed in academic texts, lied about in classrooms, drowned in dates, they had imprisoned her in museums and buried her, with floral wreaths, beneath statuary bronze and monumental marble.

Perhaps Memory of Fire can help give her back breath, liberty, and the word.

Through the centuries, Latin America has been despoiled of gold and silver, nitrates and rubber, copper and oil: its memory has also been usurped. From the outset it has been condemned to amnesia by those who have prevented it from being. Official Latin American history boils down to a military parade of bigwigs in uniforms fresh from the dry-cleaners. I am not a historian. I am a writer who would like to contribute to the rescue of the kidnapped memory of all America, but above all of Latin America, that despised and beloved land: I would like to talk to her, share her secrets, ask her of what difficult clays she was born, from what acts of love and violation she comes.

I don’t know to what literary form this voice of voices belongs. Memory of Fire is not an anthology, clearly not; but I don’t know if it is a novel or essay or epic poem or testament or chronicle or … Deciding robs me of no sleep. I do not believe in the frontiers that, according to literature’s customs officers, separate the forms.

I did not want to write an objective work—neither wanted to nor could. There is nothing neutral about this historical narration. Unable to distance myself, I take sides: I confess it and am not sorry. However, each fragment of this huge mosaic is based on a solid documentary foundation. What is told here has happened, although I tell it in my style and manner.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn