In July 1919, the Chicago Defender published an article about a June lynching in Longview, Texas. The paper reported that white vigilantes murdered Lemuel Walters on June 17 and described the circumstances surrounding the lynching. While coverage in the white press accused Walters of burgling a home and threatening a married white woman, the Defender suggested Walters had been in a consensual relationship with the woman, was a guest in the house, and even that she had declared her desire to obtain a divorce and marry Walters, if it were legal.

This report fanned the flames of white rage and provoked a thousand of the town’s white residents to riot. According to the Texas State Historical Association, “racial tension was especially high immediately before the riot because two locally prominent Black leaders had urged Black farmers to avoid local white cotton brokers and sell directly to buyers in Galveston.”

Because of its critique of racism and celebration of Black independence and self-defense, the Chicago Defender was a perennial target of white supremacists who sought to disrupt its distribution, typically by attacking its reporters and printers.

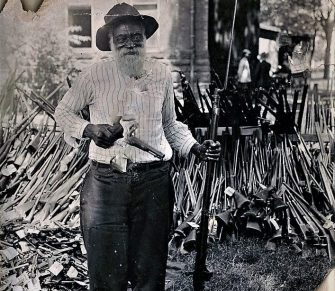

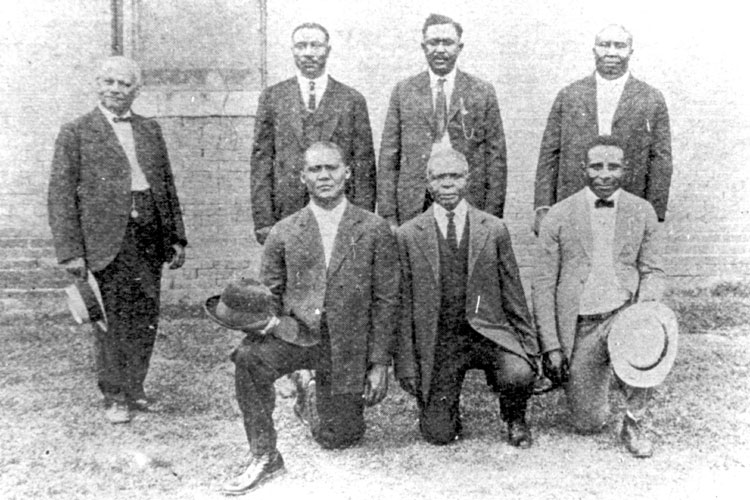

Daniel Hoskins with guns deposited at Gregg County Courthouse, Longview, Texas, July 13, 1919. Source: Library of Congress

In 1919, the local distributor of the Defender in the Longview community was Samuel L. Jones, a school teacher and labor rights advocate.

When the Walters article appeared in the Defender, white citizens of Longview concluded that Jones was its author. A mob formed and found Jones by the town courthouse on July 10, 1919. He was beaten, but escaped to find his friend, Dr. Calvin P. Davis, who immediately began to organize for their defense. That evening, Jones hid at a relative’s house while Davis and 25 other armed Black men set up defensive positions at Jones’ house and waited.

A dozen or so armed whites arrived at Jones’ house and tried to enter by force, but the Black men opened fire on the white attackers. Several of the white men were injured. The mob fled and went to alert their friends and relatives. Grown now to nearly a thousand men, incensed by the specter of Black self-defense, the white mob returned to Jones’ house and burned it to the ground. They also destroyed several other properties owned by Black residents. Jones and Davis both managed to escape from Longview with their lives, but Davis’ father-in-law, Marion Bush, was chased down and killed by the mob on July 11.

Black residents called upon the town’s white mayor, sheriff, and governor for aid. During the white rioting, the only law enforcement present were the local police. State troopers and the National Guard arrived in the next week to monitor the situation. A curfew was enacted, as was martial law.

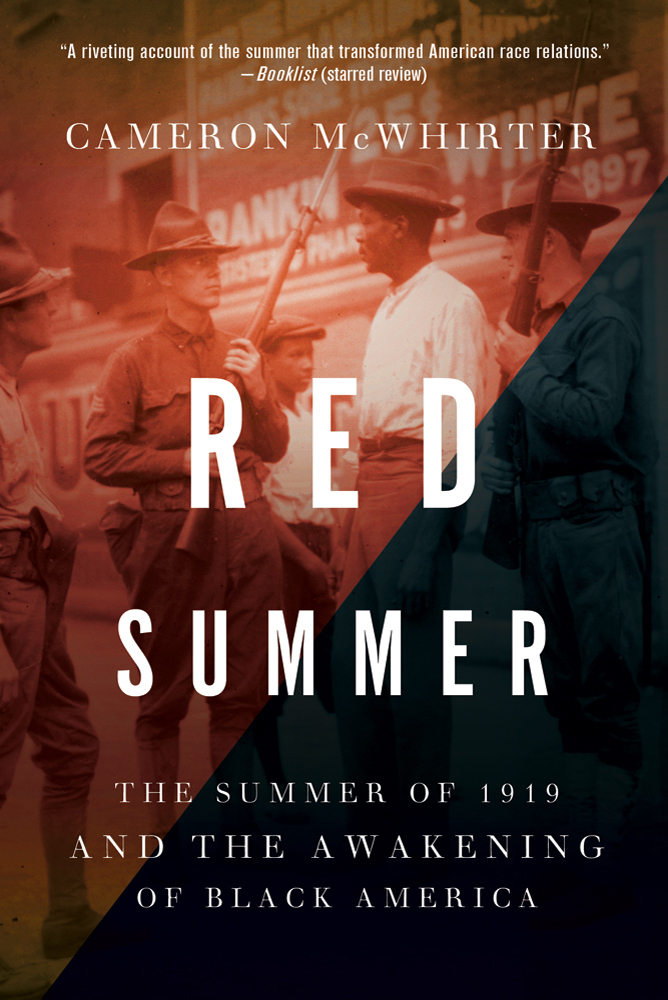

The Longview Riot is one example of the epidemic racist mob violence of 1919, a period known as “Red Summer.”

Read more about the 1919 events in Longview, Texas, at the Texas State Historical Association and in the Crisis article from October 1919 (“The Riot of Longview Texas,” p. 297).

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn