I executed the COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement activity with my 9th grade U.S. History students. They were engaged and enraged; curious and collaborative; eager to learn more and hungry for justice.

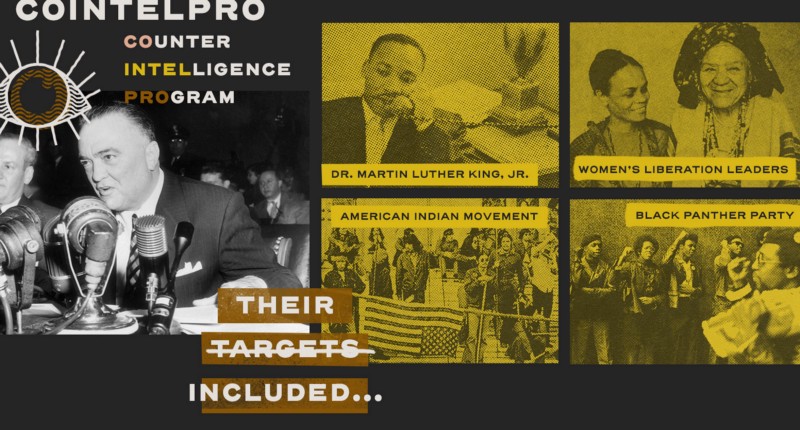

To activate their interest, I spent the first class period showing the Freedom Archives’ COINTELPRO 101 documentary. The documentary starts by exposing the COINTELPRO operations that successfully infiltrated the Puerto Rican independence, Mexicana, and Native American liberation movements and led to the incarceration and death of many activists. Since I teach a majority Latinx student population, they were immediately hooked.

The next day, we dove into the document analysis activity compiled by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. After going over key terms and background information (as suggested by Wolfe-Rocca in the PDF version of the activity), I arranged my students in groups of four and they investigated six of the included documents. For the full 90-minute block period students discussed, jotted down notes, and exclaimed in both horror and shock as they learned about a sliver of our country’s hidden history.

Unsurprisingly, many students were able to connect COINTELPRO to present day. Several of them bravely brought their own familial and personal experiences into class discussion. They shared stories of wolves in sheep’s clothing, covered by titles of police officer, government official, social worker, friend, or teacher, who had in some way or another sabotaged their family’s safety or livelihood. Per Wolfe-Rocca’s suggestion, we ended the class period as a group and candidly discussed both the risks of resistance and the importance of it.

Paradoxically, teaching people’s history leaves more room for hope than any other educational framework. When students are given permission to explore the whole truth without frills, we can discuss solutions in the form of direct nonviolent action and civil disobedience that actually mean something in the real world.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn