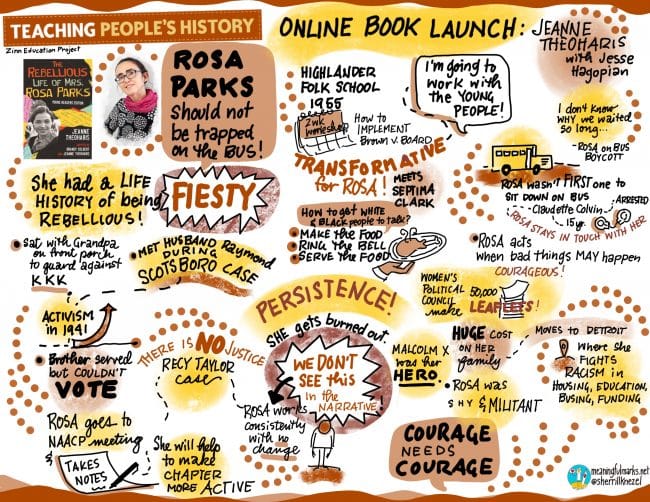

On Jan. 11, 2021, the Zinn Education Project hosted a Teach the Black Freedom Struggle people’s history class with Professor Jeanne Theoharis, who spoke with high school teacher and Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian about the new young adult book on Rosa Parks.

The class conversation, illustrated by Sherrill Knezel.

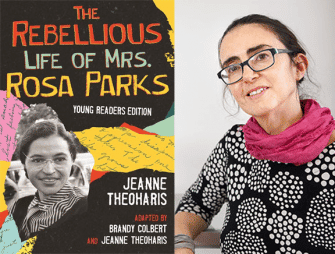

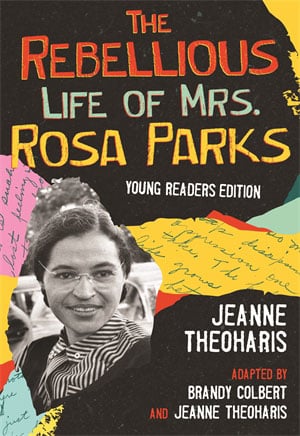

Hagopian and Theoharis discussed Parks’s activism prior to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her trip to the Highlander Folk School, and the decades she dedicated to challenging racism in the North. This session was based on The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition by Jeanne Theoharis and Brandy Colbert, to be released in February 2021.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

Mrs. Parks was not a passive activist, and to frame her as such is a diminishment to the powerful person that she was. She was not passives; she was a quiet storm!!

I learned so much about Rosa Parks’ life after the bus boycott, the isolation and hardship that she faced as a result of her activism.

I think right now, young people are just totally caught off guard by what is going on in our country today. The ones I work with are probably afraid and feel as if they are targets and hated. I know in other communities the young people may feel or think they have the right to discount others, it is impossible to tell. Rosa Park’s life gives us a road map to stay in the game and do our best for all young people.

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

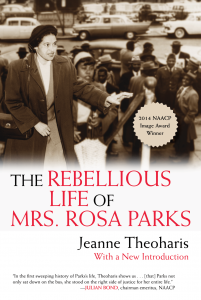

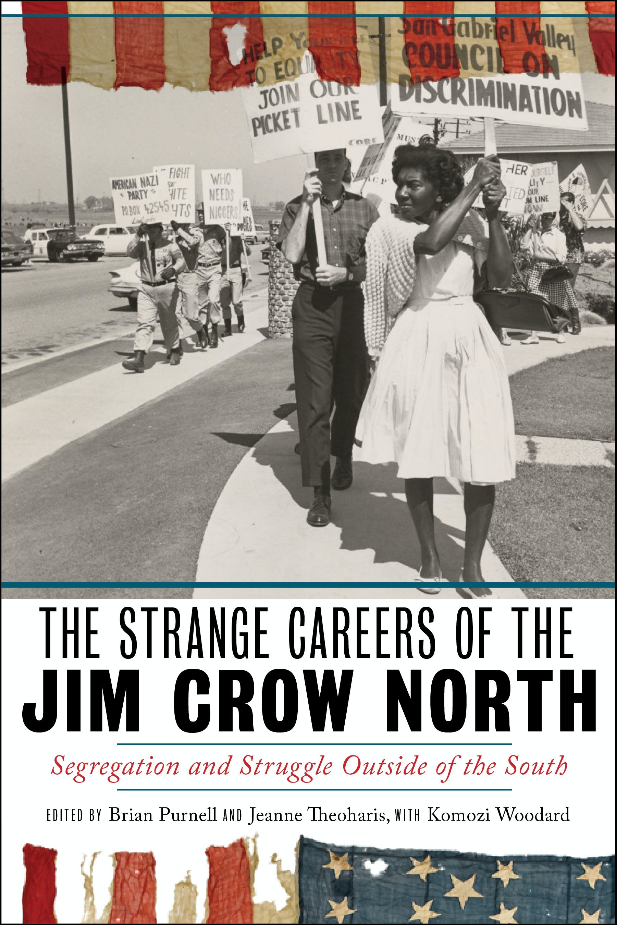

Jesse Hagopian: It is my honor to introduce Dr. Jeanne Theoharis, author of the award winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, also a must read, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History, the soon to be released YA version of the book on Rosa Parks with Brandy Colbert, and another new book released tomorrow, an edited collection of lectures by Julian Bond. I can’t wait to see that as well. Everyone should know that Jeanne actually was the mastermind behind launching these people’s historians online sessions. So we’re grateful for your vision on this project. And I’m also just so grateful to you, Jeanne, for having reached out to me to help do this session, and to my youth at Garfield. When you first conceived of the YA version you had them help work on the book. This has been an incredible process, and I’m so glad that we’re finally able to be here with you and get to celebrate. So, welcome.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. I’m so excited. Basically what Jesse’s referring to is when I first started the book, transitioning the adult biography to the YA, I wanted to make sure that I had the input of young people. So I took two groups of young people, one of which was the Black Student Union at Garfield, who read the adult book with me and helped me pick out the stories and the quotes and think about what was going to resonate. So, an excellent and an exciting journey.

Hagopian: No doubt. So, let’s jump into the history because there’s so much to learn. You’ve taught me so much through the course of this process, and I thought I knew a lot about Rosa Parks, but I just have gained so much from deepening my understanding of her vision and her body of work that is so hidden in our classrooms, in our school system, in our society. Rethinking Schools magazine described what can be learned from your new YA version of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by saying, quote, “Rosa Parks is one of the most famous women in U.S. history. And yet, all that most young people know about her is that she refused to give up her seat on the bus, and she did that courageously, heroically. But as this new adaptation shows with intricate detail, Rosa Parks should not be trapped on the bus.” So, I was wondering if you could talk about what’s wrong with the tired seamstress narrative about Rosa Parks and tell us more about her life before the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her life as an organizer. I’m specifically interested in the campaign that she and her husband Raymond worked on with the Scottsboro Nine case and her work around defending victims of sexual assault. She had been a lifelong activist. So, talk about some of that.

Theoharis: The title of the book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, actually is taken from a quote from her. She talks about having a life history of being rebellious, and in many ways that starts as a kid. It starts as a young person. Rosa Parks was shy, she’s shy all her life, but from a very young age she has a feisty side, and a feisty side that in some ways is cultivated by the example of her. She grows up with her mom and her grandparents in Alabama. One of her first memories, she’s six years old, it’s right after World War I, there’s this uptick of white violence as Black soldiers returned from the war. White violence, klan violence.

So her grandfather starts sitting out at night with his shotgun to protect the family home, and a six year old Rosa sometimes sits vigil with him. Because, as she puts it, she wants to see him shoot a ku kluxer. So very much this is a different place to begin. A lifelong believer in the right to self-defense, she has this spirit as a young person. But that spirit really turns into activism when she meets and falls in love with, who she describes as, the first real activist I ever met. And that is Raymond Parks.

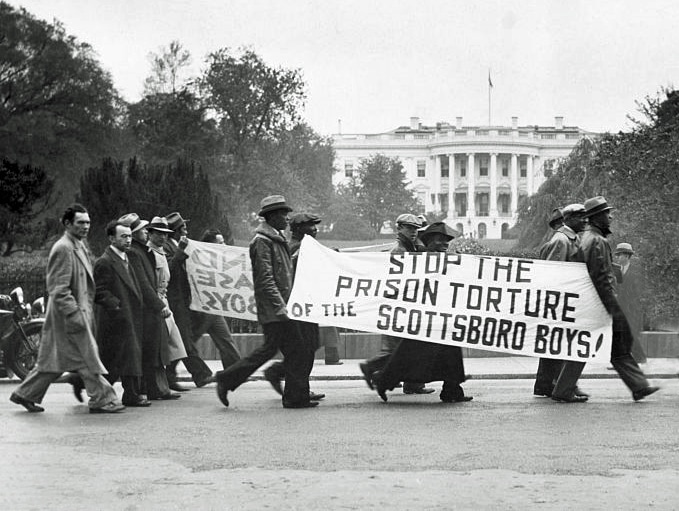

She meets Raymond Park, who is a barber. It’s 1931, and Raymond is working on the Scottsboro case. The Scottsboro case, just so we remember, are young men riding the rails, riding the train for free, as lots of people were doing during the Great Depression. These young Black men get in a fight with some young white men who are also riding the train for free, and they eject the white boys from the bus. Those boys go get the police. The police come onto the train in Scottsboro, Alabama — that’s why the case is named for Scottsboro — and begin to arrest these nine young men. In one of the other cars they find two white women, and that charge, which was originally just riding the train for free, not paying, turns to rape. These young men ages 12 to 19 are quickly tried, convicted, and all but the youngest — who is 12 — are sentenced to death.

A local movement grows in Alabama to try to protect and defend these young men from being executed, and one of those local activists is Raymond Parks. That’s what he’s working on when she meets him. They get married the next year, in 1932. And she will join him in that work: she will talk about late night meetings, guns all over the table. Even to have a meeting is dangerous, so in those first years, he’s the more public activist and I think he really provides a model of how you can collectively challenge this idea of collective protest. Now, this is going to change over the course of their relationship; she will become the more public activist and he will start working more behind the scenes. But certainly at the heart of their relationship is this shared commitment to justice.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful.

Theoharis: And, again, many of us have never heard of her husband, right? That’s another part of the story, that she has a husband, that Mrs. Rosa Parks has long hair that she keeps up always in braids and buns, but she keeps it long because Raymond liked it. This idea of Rosa Parks’ romantic life. But in many ways her activism really increased in the 1940s. She is frustrated that many, many Black people are serving overseas in World War II — and that includes her younger brother Sylvester — but can’t vote at home. She wants to register to vote, and she sees a picture in a local Black newspaper of a local NAACP meeting. And she recognized that there’s a woman in the picture that she went to middle school with, so she says she realizes that women can be part of the branch. She goes down to her first meeting, she’s the only woman there, and she’s asked to take notes. She says she’s too timid to say no, so she agrees.

It’s also branch Election Day. So on that very first meeting, they elect her secretary. She makes it known she wants to register to vote, and one of Montgomery’s most stalwart activists, a man by the name of E. D. Nixon, who’s a union activist, a Sleeping Car Porter, E. D. Nixon comes to the Parks’ apartment — and again, the Parks’ are living in the projects, in the Cleveland Courts projects. I think there are many myths about Rosa Parks, right? She’s tired, she’s old, she’s meek, she’s middle class. All of which we’re going to take apart tonight. So, E. D. Nixon comes by her apartment to bring her the materials to register to vote, and that meeting begins a partnership that’s going to change the face of American history. Because what Parks and Nixon will do over the next decade is transform Montgomery’s NAACP into a much more activist chapter. And like Jesse alluded to, one of the key issues they’re working on are issues that we would consider criminal justice issues.

And again, two kinds of issues. The first are cases like the Scottsboro case, cases where typically Black men are being wrongfully accused of crimes. In those cases, they’re trying to find legal defense, they’re trying to apply public pressure. On the other hand, it’s trying to make the law protect Black people, and in particular protect Black women in terms of sexual violence and rape. Many of us may have heard of the case of Recy Taylor in 1944, a Black woman in Abbeville, Alabama, who is gang raped. She survives it, they make her promise not to tell anybody, she turns around and goes and tells and activates a whole network in Alabama that, again, is grown because of the Scottsboro case. That network is a network of Black and white leftists, and it is through that network that Rosa Parks learns of Recy Taylor’s rape. She drives down to investigate in Abbeville, Alabama, and she and Nixon and people, and Black women across the country, begin to build a campaign to try to get justice for Recy Taylor.

And to be honest, there is no justice. They tried to push to get an indictment of the men, but there is no indictment. For a while they help Recy Taylor move out of Abbeville, because she’s in danger. But I think one of the things that we need to understand about these years is how hard this work is. They’re trying things and almost all of it isn’t really succeeding. She talks about how hard it was to keep going, because all our efforts seemed in vain. So over and over they’re trying to put up a legal defense, put up a public defense, to organize people. And over and over, they’re being thwarted. And over and over, she’s really growing, we might say burned out, by the small numbers of people willing to step forward on these issues.

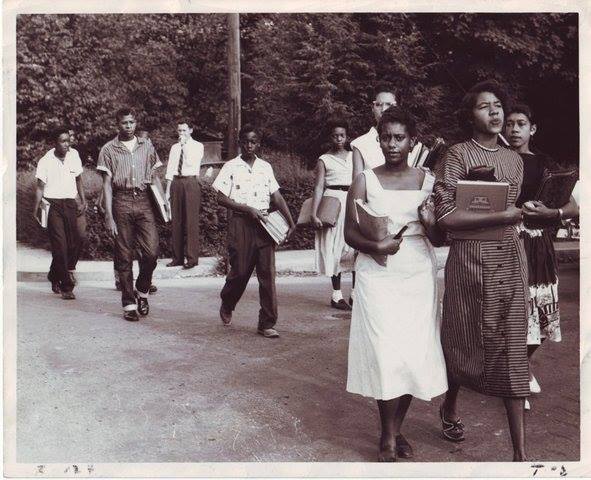

One of the real problems with the way we tell the Rosa Parks story is that it misses this perseverance; it misses how hard this work is in these years; it misses that she and Nixon and Johnnie Carr, this group of Montgomery activists in the 1940s and early 1950s, are doing this work without any sense that they’re going to see change in their lifetime. By 1954, Rosa Parks was really growing very pessimistic about her generation. We’re going to see this across her life, where she places her hopes in the militancy of young people. She restarts the youth branch of the chapter, and she’s really working on these young people to take a growing stance against segregation. And again, over and over, we’re going to see this; we’re going to see this during the 1960s and 1970s with Black Power; we’re going to see this in the 1980s when she starts her institute, Rosa Parks basically putting in, like Ella Baker, putting her greatest hope, and in some sense energy, with young people.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. Thank you for correcting so many of the myths about Rosa, and giving us a rich picture of who she was and what she cared about. It’s really great to get those details, to make her so much more human than we usually get. I’m reflecting back to the first session we did on Rosa Parks, last year when we launched this, and that lesson that you talked about how she never thought she would see change in her lifetime. And then it exploded and she was at the center of it, and just how that process repeated itself, in our own time, where we were in some very frustrating times when COVID first hit and wanting the struggle to emerge again for Black lives, and not knowing when or if it would, and then seeing the protests over the summer. It’s just an incredible lesson from her life. I wonder if you could talk about the months right before the boycott. I know she went to the Highlander Folk School, and there she met one of my heroes, Septima Clark. I was wondering if you could talk about Septima Clark’s influence on Rosa Parks.

Theoharis: As I was alluding to, Rosa Parks is getting very burned out by 1953, 1954, 1955. Her spirit is very low; she talks about feeling very bitter. And she now is working at Montgomery’s biggest department store, Montgomery Fair. It’s a segregated department store, which means that Black people can shop there, but they can’t try on clothes. Rosa Parks is working as an assistant tailor in the men’s shop, which means that she’s spending her life, or her work life, basically sewing and tailoring white men’s suits. Then she’s sewing on the side at night to make extra money. One of the people she’s sewing for is one of the few white civil rights families in Montgomery, that’s Virginia and Clifford Durr. Virginia Durr is a longtime civil rights advocate, and she is affiliated with the Highlander Folk School that Jesse just mentioned.

In the summer of 1955, Highlander, for people who don’t know, Highlander got started in 1930 as an adult organizer training school with the philosophy that people are best equipped to solve their own problems and come to solutions for their own problems. Again, it gets started during the Great Depression. They need to be trained to have that leadership. So now in the summer of 1955, Highlander is going to do a two week workshop on implementing desegregation. And again, where we are in history, we’ve had Brown [v. Board] in 1954. But again, the Supreme Court, to get that unanimous decision in Brown, puts off the second half of the decision, what scholars often called Brown II, or the implementation half of Brown, to 1955. That’s when they come back with those very famous words. They’re just looking for implementation with all deliberate speed. They basically give it back to the states for oversight, right? So what Brown II signals to civil rights activists like Rosa Parks, like Septima Clark, is that there’s going to be no implementation unless people push for it. The Supreme Court basically puts no timetable, no teeth into it. So Highlander’s having this workshop that summer to bring people together, to strategize about implementation. They have a scholarship for someone from Montgomery and Virginia Durr recommends Rosa Parks.

And Mrs. Parks decides to go. This is a big deal, to take two weeks off of work, but she does. And it is really a transformative experience for a number of reasons. One of which is meeting Septima Clark. Clark is also a longtime activist, she’s a teacher, she fought to first get Black teachers hired in Charleston, then to equalize pay. And she had recently come under attack because one of the things that South Carolina did after Brown was basically say you can’t be in the NAACP and work for the state. You can’t be a teacher and be in the NAACP. So Septima Clark refused to give up her membership in the NAACP and she got fired. She’d been there for 40 years, and she lost her pension. And Rosa Parks is kind of in awe of Septima Clark. She feels like she gets there and she’s so nervous, she’s so bitter, and Clark is so calm. She just wants to be like her.

I think this is a moment, for me, where you remember how people that we consider heroes also had mentors. Similarly, I saw somebody put in the chat about Ella Baker. Ella Baker is also a mentor of Rosa Parks, and they meet at a workshop when Baker organizes a leadership training workshop in 1944, when Baker was the director of branches for the NAACP. So both Baker and Clark provide this model for Rosa Parks in terms of how to be a long term woman activist.

Another thing that she loves about Highlander is that it’s interracial, it’s about half Black, half white. It’s run by Myles Horton, who is white. And she loves how sassy Horton is. Journalists would come and they would ask him how he manages to do this, “How do you get Black and white people to sit together and eat together?” And he would just basically say, “Well, you know what, first, we make the food. Second, we ring the bell. Third, we serve the food.” And she loved it, because it was just making fun of the absurdity of segregation. So she really feels like her spirit starts to lift.

Still in awe. Like any good adult organizer, like in any leadership training school, at the last day they do a go around. What are you going to do when you go home? It gets her and Rosa Parks says, “There’s never going to be a mass movement in Montgomery. It’s the cradle of the Confederacy. It’s too violent, and Black people aren’t unified.” She said, “I’m going to go home and work with the young people.” This is four months before her bus stand. Again, we see her recommitting to where she’s going to put her energy in young people. This is, again, one of the things to me that’s really motivated the YA book is that Rosa Parks is constantly taught except that what we’re teaching young people doesn’t actually do justice to what she believed in and what she did.

So she leaves Highlander more determined to cultivate youth leadership, because she’s not at all convinced that there’s going to be any kind of groundswell. One of my favorite quotes from Rosa Parks, when, after December 1, 1955, when she makes her stand and then that night the Women’s Political Council springs into action and calls for a boycott on the Monday when she’s going to be arraigned in court. Then, in this incredible moment, on Monday, everyone stays off the buses. And she’s delighted. But one of my favorite quotes from her, as she says that she thinks to herself, “I don’t know why we waited this long.” So to her it’s like, “Why did it take this long?” And I think this is also one of the things that I take so much inspiration from her, this ability to keep going even when you can’t necessarily see that it’s going to change something, or even though you can’t necessarily see how it can play out, but you just keep drawing things and you keep doing things.

Hagopian: No doubt. We need that inspiration a lot in the lulls in between the ups of the struggle and moments like this, when we see white supremacists surrounding the capital, we need to be able to keep going in these times. And I think she is an incredible example of fighting through the hard times to build up the expertise about how to lead a movement when the time is ready. So, I appreciate that a lot. And just seeing how she learned from other mentors is so important, too. I want to get to that moment now, because what Parks of course is most known for is taking her stand by refusing to stand and move for a white man on the bus on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, and she rejects the bus driver, James F. Blake’s order to relinquish her seat in the “colored section” to a white passenger, after the “whites only” section was filled. I wonder if you could tell us about how she came to make this act of civil disobedience and how she inspired the boycott? I’m especially interested in the leading role that women played in the boycott.

Theoharis: Right. So a couple of things. The first is this is not her first act of bus resistance. Nor, as I think many of us know, she’s not the first person to get arrested on the bus for resistance. There’s been a trickle in Montgomery, mostly of women who have refused to give up their seat on the bus and been arrested. One case in 1944 was Viola White, who refused to give up her seat on the bus, was arrested, and decided to pursue her case. In response, police rape her daughter, and then the state does all this tricky stuff to tie up her appeals, so she actually dies before her case goes anywhere. I think many of us are now familiar with the case of Claudette Colvin. Like nine months before Rosa Parks makes her stand, a 15 year old by the name of Claudette Colvin — and Colvin is studying segregation in school. She had been politicized by the case of one of her classmates, a young man by the name of Jeremiah Reeves, who was having a relationship with a young white woman and that got found out and he basically got accused of rape, brought in, put in the electric chair, made to confess. Again, it’s a case a little bit similar to the Central Park Five.

Rosa Parks worked on this case, and it’s a hugely politicizing event for Claudette Colvin. Reeves had gone to her high school. And Claudette had worked with Mrs. Parks in the NAACP youth, too. Colvin is arrested in March for refusing to give up her seat. Then in May, the judge does something tricky and in Colvin’s case, when Colvin is arrested, the police basically carry her off the bus and have their hands all over her and she’s struggling, and so Colvin actually gets arrested on three charges: a disturbing the peace charge, a segregation charge, and an assaulting an officer charge. Even though Colvin is this very petite young, little 15 year old. Then the judge strategically throws out the segregation charge, throws out the disturbing the peace charge, so that the only charge that Colvin is convicted of is assaulting an officer, which Virginia writes about being just the most absurd thing ever. The judge makes it much harder to pursue a legal case on behalf of Claudette Colvin, and at the same time, I think one of the things we see in Montgomery is a similar thing that we often see today, which is that adults don’t always trust young people and youth movements. So while people have been very outraged in the days and weeks after Colvin was arrested, support for Colvin starts to wane and Colvin talks about really the only adult that keeps up with her that summer is Rosa Parks. And Mrs. Parks is trying to get Colvin even more active in the youth council and sometimes Colvin would stay over at the Parks’ apartment when she couldn’t get a ride.

So I think sometimes there are so many kinds of missed and misimpressions. One of the new ones, I think, is this pitting of Colvin against Parks, which I think doesn’t do justice to either of them. It doesn’t do justice to what happens in Colvin’s case and who Colvin is and the fact that Colvin is also going to step up a second time and Colvin is going to be one of the people actually on the federal case that goes to the Supreme Court.

I think we erased that leadership of her and another young woman by the name of Mary Louise Smith, who’s arrested about five months after Colvin is — also for refusing to give up her seat on the bus. Two teenagers. So fast forwarding to December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, she’s coming home from work. Again, this is not her first act of bus resistance. One of the things that she refused to do was that some bus drivers would make Black people pay in the front but then get off and reboard from the back, so they wouldn’t even walk next to the white customers, and Rosa Parks refused to do this. This bus driver had thrown her off the bus 12 years earlier for refusing to do that. Other bus drivers had thrown her off the bus and considered her uppity. So again, this is not her first time. But I think what makes this — and I think I was starting to say this a few minutes ago — really courageous is she knows what can happen. Claudette Colvin had been manhandled; Viola White’s daughter had been raped; to risk an arrest as a Black woman is to put your body in jeopardy. So she knows the danger, and she talks about how she didn’t know if she would get off the bus alive.

But to me, almost more courageous is the ability to act when there’s no evidence that anything good is going to come out of it. She’d made stands before, other people she knew had made stands before. There’s nothing to suggest tonight, and I think this is one of the worst ways we teach this story, that somehow if she sits down, everybody’s going to rise up. That’s just not how it works. So I think the courage to be able to do this without seeing that it necessarily is going anywhere now . . .

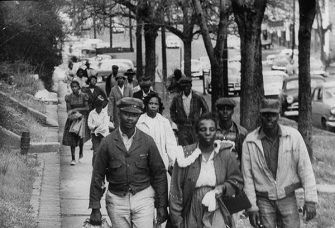

Part of why it goes somewhere is because of the leadership of a group of Black women who are part of a group called the Women’s Political Council, who had been organizing around bus segregation already and who leapt into action that night after Rosa Parks decides she is going to pursue a legal case. And in the middle of the night, the head of the Women’s Political Council, Jo Ann Robinson, she’s a professor, she basically sneaks into Alabama State College where she teaches, and with the help of a colleague and two students runs off 50,000 leaflets, basically saying, “Another woman has been arrested on the bus. Boycott on Monday.” Then in the early morning hours of Friday, the women of the Women’s Political Council take those leaflets and they fan out all over the city and leave them in barber shops, in schools and churches, everywhere to let people know. So I think sometimes [people think] it’s King who planned the boycott, or somehow it just happens. It doesn’t just happen. It happens because people make it happen. And the old mimeograph machine; I love the mimeograph machine.

Hagopian: Right. That’s so great, that there had to be this whole apparatus and years of organizing before this event, and that no one knew that this was the time that was going to set this off. It’s so important when we think about how to make social change today. And the leading role that Black women have always played in the struggle has to be put front and center there.

Well, I want to talk [about] this last part of her life, because it’s the part I really never knew and felt the most bitter about not being taught this history. For those of us educated in the school system, one of the most surprising things, I think, for us is that Parks’ life after the boycott is so incredible. She moves to Detroit, she becomes involved in the Black Power movement — and this is not the image that we often get taught about her. Can you say more about how she became involved with Black Power activists and what kind of effort she did after the boycott?

Theoharis: One thing that I think we often also erase in the story is that Rosa Parks’ bus stand takes a huge cost on her family. She loses her job, her husband loses his job, they never find steady work ever again in Montgomery. Eight months after the boycott was successful, they still can’t find work, they’re still getting death threats. So they decide to leave Montgomery and move to Detroit. Her brother Sylvester is already living in Detroit, [and] some of her cousins are there. But again, I think like Jesse just said, most of us, if we know that Rosa Parks moved to Detroit. It’s often as the last sentence would be “and then she lived happily ever after” is the implication. And that’s not what happens.

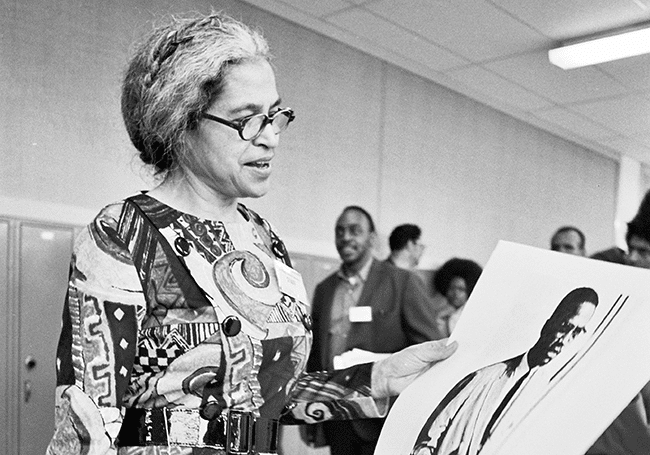

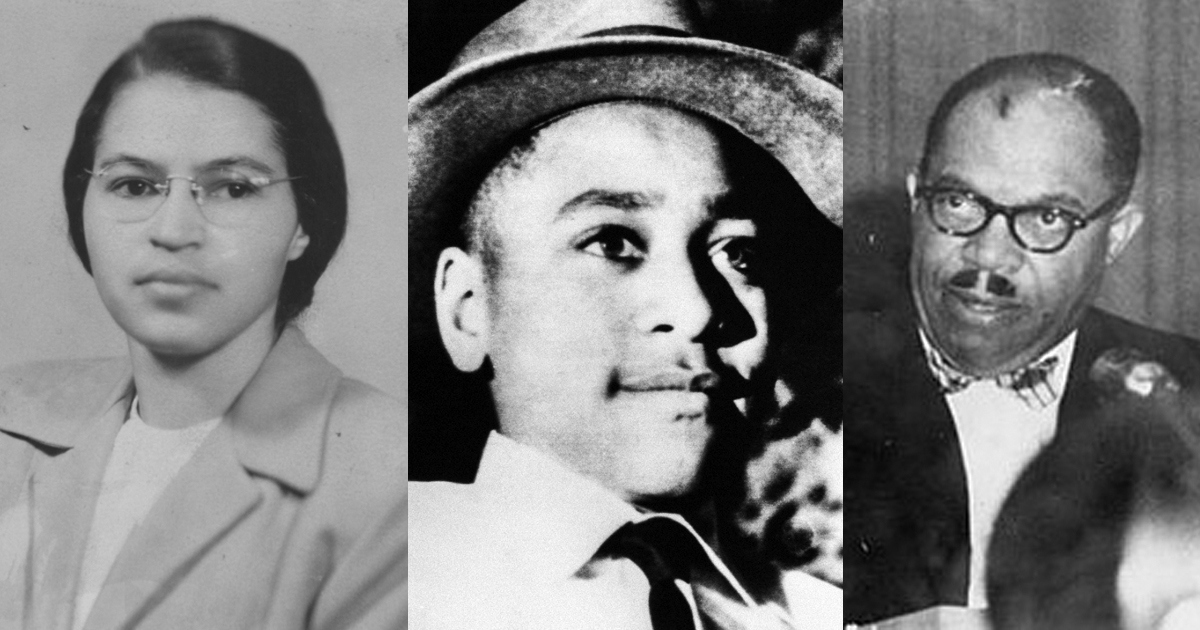

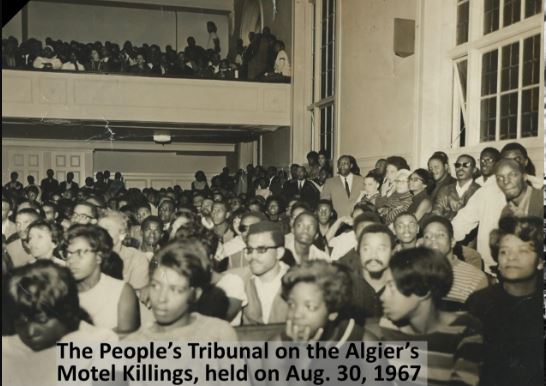

Rosa Parks spends more than half her life in Detroit, number one, fighting the racism of the North. She will describe Detroit as the northern promised land that wasn’t. While the signs of segregation on buses are thankfully gone, the systems of segregation — in schools and housing and job discrimination and police brutality — she talks about are much the same, from Montgomery to Detroit. So she will spend the second half of her life fighting those systems of racism in Detroit, in and alongside a growing Black Power movement, both in the city and in the country. I think one of the things that also teaches a fuller sense of Rosa Parks is that I think we have this very one dimensional idea of what Black Power is. It’s male and it’s loud. Like shy, middle aged women who dress conservatively somehow are not and don’t have radical politics. And I think Rosa Parks shows us that you can be shy and be a militant; you can be a conservative church lady dresser and still believe in Reparations; sit on all sorts of prison defense committees; be part of this People’s Tribunal to hold the cops accountable for police brutality during the 1967 Detroit Uprising; [and] believe in self-defense. She will describe Malcolm X as her personal hero. She meets Malcolm in 1963 for the first time because he wants to meet her.

So the second half of Rosa Parks’ life, like the second half of the book, was much harder to tell and required doing a lot of interviews and oral histories to detail this part. Because again, even when people had interviewed Rosa Parks, they tended to only ask her questions about Montgomery, even when they’re interviewing her in Detroit. So I interviewed Peter Bailey, who was one of Malcolm X’s lieutenants in the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Mr. Bailey said to me that there were two people that Malcolm was in awe of in the Civil Rights Movement. One was Fannie Lou Hamer, and the other was Rosa Parks, and he would talk about them. So they meet, and to me, one of the interesting things in terms of thinking about Rosa Parks and Malcolm X is, again, going back to this point we were talking about before, and that people have put in the chat, about courage needs courage, right? Our heroes need other people to help them continue forward.

So thinking about why both Malcolm X needs Mrs. Parks and Mrs. Parks needs Malcolm X, then that example of Malcolm X is very good at articulating the racism of Northern liberalism, the wolf in the fox he’ll talk about. And Malcolm needs Rosa Parks because she is such a long distance runner. So just thinking about that meeting, they see each other for the last time a week before Malcolm’s assassinated. He comes back to Detroit, he gives what’s often described as the last message. She’s getting an award that night. They have their longest conversation, she gets him to sign her program, her fangirl moment. So again, this thinking about this relationship between her and Malcolm and Queen Mother Moore. She and Queen Mother Moore, well many people would tell me that you’d go to these Black Power events, like the Black Power Conference in Philly, and there sitting in the front row would be Queen Mother Moore and Rosa Parks. Any sort of Reparations events, there will be Queen Mother Moore and Rosa Parks.

Hagopian: As we’re waiting for questions to come in, I’d like to ask Jeanne about why she adapted her book into a YA version. So, do you want to talk about that process a little bit more and what you hope to get out of the new YA book?

Theoharis: From the beginning, when the adult book just came out, people have been asking me to do a young adult version, to do a kid’s book. And I resisted at first. One of the things, when I first did the adult book, I was getting her out of the kind of children’s curriculum. One of the things that was so incredible when I did the research for the adult book was discovering that there was no serious footnoted adult biography of Rosa Parks until I did mine. That was astonishing to me, again, given how famous, how well known, how honored Mrs. Parks is. But I started to feel, and then I did A More Beautiful and Terrible History, and I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways we tell this history and the contemporary misuses of it.

Again, my critiques of the way that it gets taught. I started to feel like it wasn’t enough to just be critiquing what gets taught. Part of it is to you have to start to have skin in the game, right? And to start to have people doing the research, then moving into doing young adult adaptations. And the adaptation for the book was in collaboration with Brandy Colbert. People know Brandy Colbert, she’s a YA novelist. If you don’t know her novels, they’re amazing. But the idea was, and there’s a little bit that I also got to take some of the insights from A More Beautiful and Terrible History into this book, as well. For instance, there’s a chapter on the March on Washington. Rosa Parks is one of the women both honored and marginalized at the March on Washington. But the March on Washington chapter also talks about the ways that the March on Washington is policed, is monitored, surveilled, and is unpopular at the time. So part of the idea is that Rosa Parks’s life is so big, it takes us through so many parts of the Black Freedom Struggle that it really gives us, I think, as educators, a way to talk about a broad swath of the Black Freedom Struggle across the 20th century.

I guess the last thing I would say is that I began my career after college as a high school teacher teaching African American history in Dorchester, at the Jeremiah Burke High School in Boston. I know both the power of teaching Black history in high school and also know the need for much more substantive, serious resources and taking people like Rosa Parks off the poster, off the little pullout in the book, and really fleshing them out. So in many ways this was a little bit full circle for me in terms of coming back to really where I started.

And I think we might now have on the call one of the young people who helped me with this, a student at Garfield, Bethel. I don’t know if you’re here. Say hi in the chat. Bethel was one of the young people in Jesse’s [class] who read the adult book with me. We really thought about in each chapter what quotes and what stories we needed for today, and really helped me think about how the book spoke to the present and spoke to young people, and in a really granular way, with quotes in every chapter, just making sure these are the ones that were important, these are the ones that really resonated, and so I’m so excited for you to see it. And I have to say, I’m so excited for everyone here. It’s a huge honor to get to launch the book tonight with all of you. This took a long time for me to get to this place, to do this book. So, to get to bring it into the world, in this community, with this group of educators, and hopefully for people to spread the word. I think one of the things I’m a little bit worried about in this moment, with so much news and the pandemic, I don’t even know how people, like there’s so much stuff coming at us that it’s hard to absorb anything. So I’m really grateful that people are here and I would be grateful if people told people if they thought the book would be helpful in teaching. That would be great.

Hagopian: No doubt. I’m so glad this book is coming into the world. It’s made so much richer that you came and we worked with the youth at Garfield and they learned so much through the process. And Bethel was such a leader in reading the adult version. I mean, she marked it up and had underlines and highlights and tabs all throughout the book about the parts that had to be included in the YA version, and ways to make it translate well to a younger audience. That was a great process to get to work with her, so I appreciate you helping facilitate that. We’re getting some good questions in the chat. Someone wanted to know how Rosa Parks was received in the African American community. Was she isolated or thought of as too radical? How was she treated? And I think we were talking in the break about after the boycott, some of the ways she was treated by the NAACP, but then also just politically, or how her politics were received.

Theoharis: Right. One of the things that I think many people know, the Library of Congress now has this incredible set of Rosa Parks’ papers, including a small trove of her personal writings. I think one of the things that, to me, is most gut wrenching about the personal writings is how much she talks about how hard it was to dissent, how hard it was to be an activist, and how lonely she felt and how crazy she felt. And how much pressure there was both in terms of other Black people and then also in terms of the white people and the dangers of being a Black rebel. All of that material is digitalized, so you can go to the Library of Congress site and look for some of her personal writings. I should also say, I made a website for the adult book, it’s RosaParksbiography.org, and there are all sorts of resources there. There’s both a narrative and a timeline. But also some primary sources.

A second resource is, we did at Rosa Parks’ class as we began this civil rights mini-course in March, and then Bill Bigelow made an incredible mixer activity that was then published in Rethinking Schools recently. And then the third thing is on the Beacon website, Val Brown, who is one of the founders of Clear the Air, she did a teacher’s guide to the YA version, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks Young Readers’ Edition. So there are three different resources for people to be able to use to teach Rosa Parks differently, and to teach this bigger history. And in particular, I would want us to be teaching one of the throughlines in her activism is what we call criminal justice and police brutality. These issues and the fight for a more just criminal justice system, the fight to make police accountable, run through her life. Really getting to see that, I think, changes. One of the other ways Rosa Parks is trapped on the bus, but she’s also trapped in the way distant past. Because bus segregation seems like something . . . and she would talk about how she did a lot of public speaking, particularly towards the end of her life. She would say people would ask her if she knew Harriet Tubman. Obviously Harriet Tubman was [dead].

I think when we look at the all the work that she’s doing around criminal justice, around police brutality, around wrongful incarceration, trying to get justice around sexual violence, it really makes the story much more current. And it makes the ways that people tend to pit the Civil Rights Movement against Black Lives Matter even more illegitimate, because there’s no question when you look at all of the things Rosa Parks is doing. And I mentioned this before, briefly in 1967, that there’s an uprising in Detroit, and there’s massive police violence during that uprising. Representative John Conyers will call it a police riot. One of the worst [things] is that they killed three young Black men. On the fourth night of the uprising, I think, at the Algiers Motel, it was the subject of that horrible movie a couple years ago called Detroit. So these three young men are killed by police, the cops aren’t indicted, and then Detroit newspapers aren’t even following up. So they’re not even reporting on it. So basically, Black Power radicals, inspired by H. Rap Brown, decided to hold a People’s Tribunal in Detroit to try to at least expose what happened. They asked Mrs. Parks if she’s willing to be on the jury and she says yes. So it’s this very militant event, it takes place in Reverend Albert Cleage’s church, the Shrine to the Black Madonna. But I think when you see Rosa Parks there, you see the ways that many commentators today tried to be like, Black Lives Matters and the nice Civil Rights Movement, it just falls apart when you see these continuities in terms of the ways that . . . And then she’s on all these prisoner defense committees in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Angela Davis, Joan Little, the Wilmington 10, the RNA 11 and all of these Black political prisoners. Mrs. Parks went to the shrine all the time for lectures, for meetings, she was very close with Reverend Cleage.

Hagopian: Excellent. Somebody else asked in the chat about how they make this relevant to their students today. What’s the legacy of Rosa Parks, and lessons that we can gain from thinking about struggles against white supremacy today, as we just saw our capitol building overrun with confederate flags and violent white supremacist?

Theoharis: I think there’s a couple of lessons. The first is, what I was trying to say before, which is that the connections between what she’s doing and the Civil Rights Movement is doing, of issues that we’re grappling with today, particularly around criminal justice. These very clear throughlines she’s doing, she also sees the Black Freedom Struggle as embedded in a global anticolonial struggle. She’s an early opponent of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. She’s an early activist around South African apartheid. She sits on a war crimes tribunal around war crimes in Central America in the 1980s. She has a global vision, similar to how Black Lives Matter has a global vision and understands that the situation that Black people face in the United States is paralleled around the world. I think another thing that she gives us is that she’s a long distance runner, she just keeps going, she keeps doing things, she keeps trying things. I think that gives us a way to be a real model in many ways. And then the ability to keep going. You don’t have to be able to see the end to start. I think that’s part of the genius of Rosa Parks, to me.

The other thing she gives us, so obviously I take issue with this idea that Rosa Parks is quiet. In key moments, Rosa Parks is not quiet. I did not mention this, but including when she gets arrested on the bus that night, December 1, 1955. The cops come on the bus, you can imagine the scene, and they asked her, “Well, why didn’t you get up?” And Rosa Parks is not quiet in that moment. She turned to the cops and she says, “Why do you push us around?” So, she’s not quiet. But Rosa Parks absolutely is shy, Rosa Parks is absolutely reserved. She doesn’t like to take up space. And I think sometimes, to me, seeing Rosa Parks and all the different ways that she’s involved, I think, reminds us that you don’t have to be a super confident, great public speaker, or you don’t have to be loud, that there’s all different ways to come into social justice work. And I think she reminds us of that, too. So I always think of her as a shy militant.

Hagopian: I think that’s a beautiful place to leave it, that we all have a way to participate in the struggle. I hope that the educators here will take this into their classrooms and into the social movements and build on this legacy.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chatbox.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I loved hearing about the mentorship of generations of activists, from Septima Clark to Rosa Parks to Claudette Colvin — these relationships are such an important part of this history that too often gets erased.

I appreciated the stories and the format (pedagogy) of this workshop. It is a very good model of how to run remote lessons.

Rosa Parks was mentored by Septima Clark!

That Rosa Parks had been doing these same kinds of actions for decades without knowing if any change would actually happen. Also, she wasn’t alone. This wouldn’t have happened had groups not been organizing for years.

Rosa Parks was discouraged and she kept going. Kids need to hear that.

I found Rosa Park’s connections to other activists, both locally in Montgomery and in her later life with Malcolm X, to be a very important part of the story. To teach her story in isolation does a disservice to our students who need to understand the values of mentorship, planning, and organization. While injustice can be recognized alone, it takes a community to fight it.

Mrs. Parks had Claudette Colvin come for sleepovers! The tenderness of intergenerational women’s friendships.

Being six years old and sitting with her grandfather to protect her family.

Rosa Parks herself was not confident that she would see change — but acted and persevered nonetheless. She was a “long-distance” activist for decades, (and so many others had acted, and organized, without seeing much or any change). This is MUCH more powerful as a teaching goal than the myth of the solitary superhuman single act of Rosa Parks.

I learned so much about Rosa Parks’ life after the bus boycott, the isolation and hardship that she faced as a result of her activism.

Rosa Parks was engaged in the struggle AFTER Montgomery, too! I didn’t know that.

I learned about the backlash that she faced as a result of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and how it affected her family (losing their jobs, being forced to relocate to Detriot, etc.).

The role of the Women’s Political Council in organizing the movement in Birmingham.

Rosa Parks’ life after the boycott in Detroit and her contribution to the Black Power Movement.

The dedication Rosa Parks gave to issues beyond the civil rights movement in the United States. She also opposed the Vietnam War, Apartheid in South Africa, and human rights abuses in Central America in the 1980s.

I loved learning about Rosa Park’s mentors and the young people she mentored — we all need support and guidance. Activism doesn’t work in a bubble.

Young people need to know that they are more than capable of being an activist and that activism encompasses more than marching in a protest. Take Rosa off the wall.

That I’ve been missing OUT by not attending these sessions! (And about the Highlander connection and Mrs. Parks being mentored by Septima Clark!)

How long Rosa was in the struggle and how she became tired and wanted to give up. She needed mentoring as a mentor and she did receive it. I knew she suffered from depression and thought of suicide due to the constant death threats, but I never thought of her being tired of the struggle or needing mentors. I mean it is totally human and needed by all, but it never crossed my mind.

It’s possible and important to act even if you don’t know what it will do, even if the end isn’t in sight. Rosa Parks was a long-distance runner.

The perseverance of Rosa and her involvement in myriad human rights issues like women’s rights, oppose police brutality and segregation, decolonization, anti-apartheid, the anti-war movement, youth involvement.

The story about Jeremiah Reeves intrigued me. I cannot recall ever hearing his story.

I did not know she and her family lost their jobs during the bus boycott. I did not know about the death threats they faced and her legacy with activism as she moved north to Detroit.

I got the fuller Rosa Parks story from this class rather than a snapshot of what the textbook taught me. I learned Rosa Parked was a committed activist for the fight for social justice and that there was a legacy of black women who inspired each other, lifted each other up, and led the fight for civil rights.

Rosa Parks had mentors — and how important that is even to someone as remarkable as Rosa Parks. And I also loved hearing again about the role of the women, and especially Joann Robinson and that whole group that was ready to go with the bus boycott.

“It’s a long-distance run”: not a new idea but an important reminder that change comes over time, and one should not be disheartened by the lack of huge success in the short term.

What will you do with what you learned?

Using all of these resources, I hope to teach a more in-depth and nuanced unit on Rosa Parks and her role in the Civil Rights Movement.

I will talk about Parks’s later life in Detroit, her admiration for Malcolm X, and her work with Black Power activists. That is something we don’t typically talk about in my class.

I’m teaching a 60s social justice movement class and it will be deepened by some of these insights and my knowledge of her connections with other activists.

I want to bring parts of this book, Parks’ story to other books we’re reading, including Coates’ Between the World and Me, so my class can discuss the deliberate ways that her story was hidden and changed, and the result of such censorship.

I’m always expanding my people and power unit in U.S. history, I also include more and more of this story in civics. I’m about to start geography and am thinking about how to add this to that course.

I am going to plan the mixer for the 4th-grade class I’m taking over for the rest of the year. I can’t wait.

As a human rights education advocate, I will share the book and materials with colleagues and members of our organizations, as a grandmother, I will buy the young adult version for my granddaughter, who would like to know about quiet women who used their voice when it was needed.

Incorporate into our Civil Rights Project in creating an Organizing Booklet for 11h grade.

Use it to frame discussion with my own children in our anti-racist curriculum supplementing their public school education, and also with my college students in public health, who come to the field because they see the health outcomes of inequality.

Teach about perseverance, teach about the importance of many little deeds.

I am very excited about teaching Rosa Parks as an example of the myths and misconceptions about the civil rights movement and struggle in general, in addition to a fuller version of the freedom fighter: the shy militant Black woman who questioned and was hopeless at times and persevered, nonetheless.

I am actually teaching this tomorrow as we move into an inquiry and throughline of white rage. Rosa Parks and the events in Montgomery are a great springboard to the principles of non-violence and the SNCC Sit-In movement that later unfolds.

Can’t wait to read the book to use this in my classroom — definitely want to do the mixer but want to see what else the book inspires.

I teach 4th grade. A big idea in my classroom is that “The past is what happened, but history is how we tell about it.” I think we could discuss why the story ‘that traps Rosa Parks on the bus’ is the one that gets told.

Teach students to see themselves as potential changemakers rather than learn about reified heroes. It’s so important that they really think about that idea that Rosa Parks didn’t know if what she did would effectively spark change, yet she did it anyway… and others stepped up to join the charge.

I will never teach about Parks the same. I will add more dimensions to widen her story to also include others like Viola White, Claudette Colvin, Fannie Lou Hammer, Malcolm X, her husband, and other organizations of the period.

What did you think of the format?

I loved that the chat allowed us to share resources and ideas and get answers to questions. I appreciated the small breakout room so that everyone had ample time to speak.

Love the large group, small group, large group. I do wish we had more time in the Breakout rooms because we were having a great conversation!

The format — especially with the emphasis on equity in politics and pedagogy — is superb. It’s a model for how I like to run video calls and teaching sessions.

It was a perfect amount of time for a session after a long day of teaching!

Prof. Theoharis’s stories were wonderful and the breakout room was equally inspiring because of the skilled facilitator (Room 12)!!

The solidarity of the participants was warmly received, clear and apparent, and REFRESHING!

I was skeptical of the format but am appreciative of the enormous effort it took to organize this. And I’m a convert.

I will be applying some of the unstructured structure to my own pedagogy. Specifically: The introduction non-lecture (it seemed like a reflection guided by some questions) & The breakout rooms (specifically the detailed instructions given beforehand and the reminder to ensure everyone else had contributed before speaking again).

Loved getting into breakout rooms and meeting people from around the country. I was able to take notes on a word doc through the lecture portion and then save the chat to add to the word doc for future reference. So many new avenues of research to pursue.

Seemed like a great format. Organized but also really welcoming and homey. The presenters seemed really comfortable, and it was easy to connect with them because of how familiar the space was. The breakout group was warm and well-run.

THANK YOU for making ASL interpretation possible. I will be sure to look for future Zinn Ed classes!

Jeanne’s talk was awesome, filled with compelling stories to illustrate just how false our myths about Rosa Parks are. Our breakout discussion was great, very good questions.

Loved everything. Including, somewhat unexpectedly, the breakout rooms — maybe assure people they are life-giving & not a typical breakout room and Zoom experience (since some folks left prior to that point). Often we’re exhausted at end of the day & people can feel shy to share more, but it was fabulous to connect with others in an ease-filled, enriching way (no one was “on the spot”, it was all in such a good flow — thanks to Turquoise Lejeune & I’m sure many others)

Great format — it always goes so fast. Would love to see more collaboration opportunities with social justice colleagues to talk about curriculum and what’s working or not in a remote environment.

Everything was great. I was nervous to speak but the facilitator was very welcoming.

The format works. I use a similar format in my [online] methods classes. No one can take more than about 45 minutes in a large group online. By using the breakout rooms, you could have a very large # of people without a problem. Overall the *atmosphere* of the entire session was wonderful. That you could “pull it off” after the week we just had is amazing!

Additional Comments

This was a wonderful session. Jesse did a fabulous job of facilitating. The content was so meaningful Jeanne. I read the adult book and I am excited to read the children’s version and share it with my own children and students.

Jeanne understands the power of story-telling to reach folks and convey to them this critical history.

Jeanne is a very informative and big-picture thinker and presenter!

There is so much I have yet to learn about the Civil Rights Movement.

Thank you SO much for hosting these. Incredibly valuable, both personally and professionally.

This wonderful event gave me the energy and community I needed this week.

This was really great. I signed up for it at the last minute earlier today and I am so glad I did.

This classroom is my extended family!

After the events at the capitol last week, it was great to be in this safe and proactive space.

Amazingly, I got my copy of Jeanne’s book Ta-Day! I wish we’d had her book when we were doing Eyes on the Prize. How much richer the bus boycott story would have been! But we have it now, so I’m grateful.

Glad I did not forget about this webinar, as I often do, I am looking forward to the book and am currently looking over the teaching resources.

I love all of these sessions — but I have to say that hearing Jeanne Theoharis again was about as excellent as it gets. She brings so many different pieces to this work — and has so much to share.

Presenters

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn