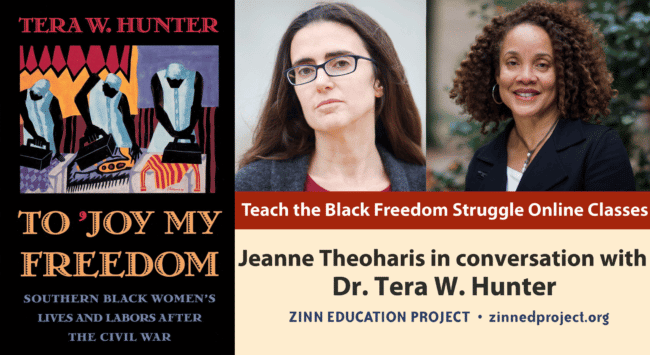

Close to 200 people joined the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class on March 11, 2021 to learn about the lives of Southern Black women during and after Reconstruction. This interactive online class featured a conversation between Jeanne Theoharis, scholar and co-founder of the series, and Tera W. Hunter, history professor at Princeton University and author of To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War.

Hunter began with the story of the 1881 Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike and went on to share many more stories of organizing by Black women for labor rights, public health, voting rights, and the right to joyful endeavors (such as dancing) from the Reconstruction era through today.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

I have attended several sessions and each one has left me in awe. One for the scholarship that is out there but I have not been exposed to as of yet and the diversity of the groups. This is such a great way to start my week. I feel energized.

The book’s title is gorgeous. And the story behind it is so revealing: that a formerly enslaved woman responds that she wants to “‘joy my freedom” when her former enslaver asks why she’s leaving.

I very much enjoyed the rapport between Professors Theoharis and Hunter. Professor Hunter took very seriously not just telling us the stories; she also emphasized the primary sources. I loved it when she asked what teachers are teaching. She broke the fourth wall — if you will. So many of the scholars who have spoken are eager to tell us about their research. I loved that she took seriously that the educators on the call had something to tell her. WOW!

I thought this was very useful and did not, like many things for teachers, pander. It was like being part of a discussion.

The central role of collective action among Black women domestic workers; leisure as a form of resistance; the role of organizing work in multiple directions to work for just labor conditions; the power of creative archival work.

The connection between stigma around COVID for the AAPI community today and the similar experience of Black folx being labeled as the primary vector for spreading TB in the early 1900s piqued my interest and definitely illuminated some simple ways to make connections in the classroom.

Wonderful — as always! These workshops have been a highlight of 2020 and now 2021 and they just keep getting better. My small group today was an amazingly diverse group of educators of all levels and multiple subjects from across the nation and was a powerful point of connection to others moved by Drs. Hunter and Theoharis’ passion for giving life and story to such important history.

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Cierra Kaler-Jones: I am so happy to pass the virtual mic over to Dr. Jeanne Theoharis and Dr. Tara W. Hunter. Thank you all so much.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. Welcome, Professor Hunter, it is so great to have you. Where I wanted to start, and I think part of the impetus for tonight’s session, is there’s been a lot of finally coming to recognize the crucial roles that Black women have played in our democracy, and certainly played in these recent elections. Certainly your work takes that story not just back to the era that I talk about, which is the Civil Rights era, but much, much earlier. We really wanted to start tonight with the 1881 Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike, to tell people a little bit about it for people who might not be familiar. What does that give us to sort of seeing this long arc of Black women’s activism in terms of reshaping and making real this democracy?

Tera W. Hunter: Well, first of all, thanks Cierra and Jeanne, and thanks to the Zinn Education Project in general for all the great work that you’re doing. Thanks to everybody who has come out; it’s great to see so many people interested in history and in this topic, in particular. And thanks, of course, for inviting me.

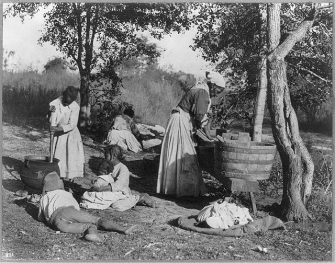

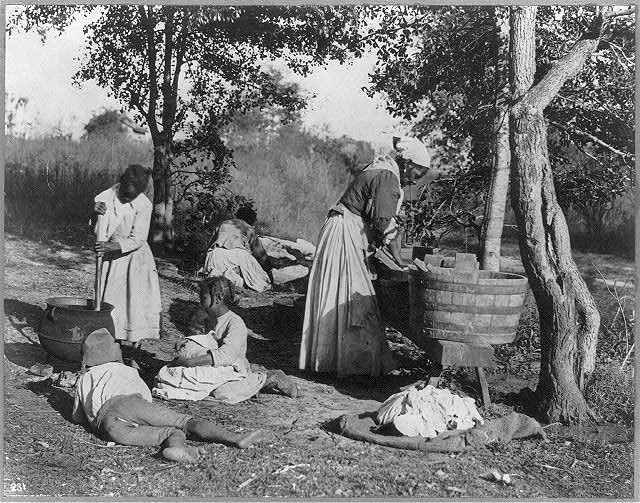

Let me just start with talking about domestic workers and then the strike, just to give people a little bit of background. So, domestic workers included the maids, child nurses, cooks, and laundresses. And they engaged in the most intimate labor, the least desirable work, conducted in the homes of white families, especially in the South after emancipation. And Black women overwhelmingly dominated these positions. They were paid substandard wages, they were expected to work very long hours, to endure insults, and sometimes even physical assaults to keep their jobs.

Laundry work happened to be the position that they preferred, given the options, because it allowed them the most flexibility, as they did the wash in their own homes and communities. And they were able to capitalize on their shared work sites and build solidarity, which they did in the summer of 1881. In July, the washerwomen, and we’re talking about Atlanta, launched a city-wide strike to improve their wages and to gain respect for their work. They mobilized supporters by going door-to-door. They had a few male allies along with them, and some of them were arrested in the process for disorderly conduct. They held meetings in local churches in which hundreds of people attended. As their numbers grew, they formed what they called the Washing Society, which was kind of a cross between a labor union and a mutual aid oriented organization. They set up satellite groups throughout the city’s five wards.

When the strike broke out in July, the women faced a lot of opposition and ridicule from employers, from city officials, and from businessmen. The most vocal was the local newspaper, The Atlanta Constitution. But opponents who laughed initially were soon forced to admit that the nickname that they gave these women, the washing Amazons, actually proved to be more symbolic than derisive in terms of showing their effectiveness. These strikers defied stereotypes about being subservient workers, they overcame hurdles that were not expected of them, and the numbers of the strikers and their supporters grew to a few thousand within a month or so.

What’s remarkable is this was a group of marginalized workers, mostly illiterate women, way too many women, and yet they organized the largest strike in the city’s history. Now, the question is, did they win higher wages? We know that some did, but the complaint of low wages persisted, so probably not most. But what’s more important, I think, is that they had a political victory in making their voices heard and asserting their rights.

One clear sign of this victory came a few months after the strike ended. They basically threatened to have a general strike of all the domestic workers in the fall of 1881. There was going to be this major event, the International Cotton Exposition, and so they threatened to strike for this first World’s Fair that was being held in the South. Now this strike would have been quite embarrassing and a black eye on the reputation of the city, and while the women didn’t follow through and carry it out, the threat was taken seriously. So this essentially is the legacy of political organizing that’s been passed down for generations.

We saw some of this kind of organizing for Stacey Abrams, when she was campaigning for governor a couple years ago, hundreds of domestic workers who are affiliates of Care in Action, which is the political arm of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, knocked on doors in Atlanta neighborhoods to get out the vote for Abrams. Now they use modern technology — they travel in minivans, [and] they use their smartphones to basically identify and target the homes of voters of color. But they were walking in the footsteps of those washerwomen from over a century before. And Abrams, by the way, stood for many of the same issues that domestic workers have long fought for, such as the expansion of health care, living wages, and quality public education. So, the washerwomen are an important reminder of the role that working class women have played in grassroots politics in the South and elsewhere, always in defiance of their marginalized economic and social status.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. Today, I’m thinking about the kind of connections between the 1881 strike and then, obviously, the strike in Bessemer. A number of people are down there in Bessemer doing that, holding that line. Often the most vulnerable workers are the ones that lead the way. So, I guess we started with the strike, but I wonder if you might tell us either about one or two organizers or another moment in this history that you bring out in To ‘Joy My Freedom, just in terms of teaching? I think one of the things we’ve talked about in this series before is the ways that there’s this gap between Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement, so maybe you could, again, introduce us to someone or some campaign that would help make it not just be a 70 year old thing?

Tera W. Hunter: The first thing to acknowledge is that the washerwomen in Atlanta were not alone in organizing strikes. In terms of domestic workers, there was one in Jackson, Mississippi in 1866, and there was another one in Galveston, Texas in 1877. Neither one of those was as impactful as the one in Atlanta, but they’re still important. One thing that’s also very striking about all three of the strikes is that they took place in the context of a wider, flourishing grassroots political moment.

In the case of the Jackson and Galveston strikes, during Reconstruction. But even with the Atlanta strike, it was happening in a period after Reconstruction, but African Americans were still very much engaged in politics, they were still active in the Republican Party. They had some significant momentum in that summer of 1881. So all of these women are building on political struggles. They were also building on other strikes that were happening in Jackson, in Galveston, that was actually part of a larger national strike that was going on with men, wage earners, especially railroad workers.

It’s hard to identify any one woman in terms of the Atlanta strike. We only know the names of the women who were arrested for disorderly conduct. But there is one person who I want to mention who is also from Atlanta [and] who is a community organizer. Her name is Dorothy Bolden. She was the daughter of a cook and a laundress, and her father was a chauffeur. She actually began helping her mother as a nine year old girl, and then throughout her adult life, she worked in various domestic jobs.

She founded the National Domestic Workers Union in 1968. This was a local organization primarily, but it grew out of her earlier organizing efforts. She had been involved in education issues and tried to get better schools for Black children in the city. Bolden used strategies that weren’t that different from the washerwomen, updated for the times: she recruited women at bus stops, on the buses themselves, and also in neighborhood meetings. And like them, she also capitalized on the political context of what was happening.

So, for example, she worked with Martin Luther King during the Poor People’s Campaign. She got his support before he passed away for the organization that she was building. And her work went beyond the South — she worked with domestic workers and with feminist allies in other cities to achieve benefits for domestic workers who had been excluded from a lot of the progressive labor laws that were passed during the New Deal of the 1930s. They petitioned and they lobbied state legislatures and the federal government to get domestic workers included in the minimum wage laws in 1974, and unemployment insurance in 1976.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. So, one of my favorite chapters in To ‘Joy My Freedom is a later chapter where you actually talk about and it seems so relevant to where we are today, where you talk about Black women’s public health campaigns, both in terms of the stigmatization the Black community was facing in terms of the TB outbreak, and then the ways not only did they push back on that stigmatization, but the public health work that they did. If you could tell us a little bit about that, what you think about it, vis-à-vis today. It just feels very resonant.

Tera W. Hunter: Yeah, it’s definitely very relevant to what’s happening right now. Just as Asian Americans have been stigmatized for spreading COVID-19, African Americans — and specifically domestic workers — were stigmatized for spreading tuberculosis in the 1910s. Now, TB, as it was called, is a prevalent disease across the nation. But in the Jim Crow South, it was called the ‘Negro servants disease.’ So, there was this idea among white residents that Black women and men who entered their homes as domestics were bringing in germs and contagion.

Now, the reality was that was not true. Obviously, Black people were not the sole carriers of TB and nor were they the primary carriers of TB. But on the other hand, African Americans did suffer disproportionately due to the disease because of poverty and Jim Crow. Black neighborhoods were literal dumping grounds for the garbage and sewage drained from the affluent neighborhoods, the homes of white people primarily, on elevated higher land. They lacked running water, they lacked sanitary conveniences. So, in response, African Americans created their own public health campaign to challenge the negative associations with the disease, but also to address the real public health issues.

Among the most prominent activists was a group of women who organized the Neighborhood Union. This organization was started in 1908 by Lugenia Burns Hope. Hope was a teacher, social worker, community activist, and the wife of John Hope, who was the president of Morehouse College. The Neighborhood Union sponsored lectures, they gave out information on disease prevention and care, they did their own research. They focused a lot of attention on women’s issues, on maternal care in particular, on child health care issues. And most importantly with respect to TB, they opened up community clinics. So again, a parallel with today, we see Black physicians in different parts of the country doing the same thing. They use volunteer Black physicians and nurses to basically run those clinics that they operated in Black neighborhoods.

The nucleus of the Neighborhood Union program was primarily that kind of self activity dealing with filling in the gaps where the government and other organizations failed the Black community. But they were also advocates. They were very much engaged in pressing the government, the local government, the county government, to do more, to do better. They lobbied for paved streets, for the city to take better care of the streets, for the city to get rid of open sewers and to remove foul privies.

Now, one of the things that’s really interesting about the Neighborhood Union, well, two things, is the way that it organized itself. They divided the city into neighborhoods, sort of sub neighborhoods, and they put women in charge of each little cell. That basically allowed them to be able to communicate very broadly with virtually every Black person in the city. But, what it also did, it also brought in the leadership base, it made it necessary to include working class Black women, domestic workers in particular. So, it’s very interesting that this was a cross-class alliance of women. There were domestic workers who were in the leadership, who were officers at the top of the hierarchy of the organization, as well as the community neighborhood organizers. So domestic workers along with professional women and middle class women, like Lugenia Burns, basically ran that Neighborhood Union. And that organization was also important in helping to start the social work program at Atlanta University. So, that just shows the impact that it had beyond the work that it was doing in the early 20th century.

Jeanne Theoharis: We know so little about this public health activism and I think if people know anything, they point to, for instance, the Black Panther Party medical programs. What do you think changes when we bring the timeline back and see that this is not just the Panthers and the Young Lords in 1970?

Tera W. Hunter: I think it just tells you that African Americans have been mobilizing on every front. We’ve been mobilizing on all the issues that face us, be it healthcare, be it economic issues around jobs or the lack of jobs, or political rights. I think that’s one of the things that it shows is there’s this long legacy of African American political activism. On every issue that we can dream up today, they’ve already done it in decades and centuries passed.

Jeanne Theoharis: Which brings us to another aspect of To ‘Joy My Freedom, which is the ways that you also center the leisure, and the struggle for leisure. Obviously, in a book that foregrounds labor struggles, that foregrounds public health struggles, you also put leisure right next to those key sites of struggle, a key area of freedom. I would want you to tell us a little bit about those struggles for leisure and what was crucial in them, and also what it means to put them alongside, and why you put them alongside, labor and public health, and why we need to.

Tera W. Hunter: When I started conceptualizing To ‘Joy My Freedom, which began as my dissertation, one of the first things that interested me is I wanted to really write about these women as fully dimensional human beings. So, a lot of the earlier work, the earlier scholarship on domestic workers, was really not interested in the women themselves. It was more interested in the households that they worked in, the middle class households, the upper class households. So the domestics were sort of appendages in those homes. In the way that scholars would have thought about them. They weren’t really interested in them as people. So I wanted to write about these women as people, as workers, as mothers, as wives, as sisters, as friends; to look at their involvement in churches and secular organizations and also to look at their leisure activities.

And what I found was domestic workers were eager participants and consumers of all the popular cultural events and venues that were available during their time. Vaudeville shows, fairs, silent movies, holiday celebrations. But the activity that was probably most popular and also most controversial was public dancing. There were these public dance halls, also known as juke joints, that were places where people would go and dance. But they were often associated with other kinds of activities that were considered illicit, like gambling, drinking, and prostitution. Part of the controversy had to do with the proximity of where these dances took place. There’s a lot of pushback from city officials starting in the 1890s: they started to call for the removal and the outlaw of what they call the ‘Negro dance halls.’ They saw them as crime breeders and a disgrace to the city. And in this instance, it’s not just white public officials, it’s also leading African Americans, who are also opposed to these, for reasons that you might suspect, having to do with respectability politics. So there were several of those.

One particular minister took a leading role in denouncing the sites. They were also critical, not just of the locations and what was happening in proximity, but also with the dancing itself. First of all, you have women and men dancing together, which was somewhat of an issue because at the time respectable company would have invited dancing, but just to have a public place where anyone could go, where women and men would intermingle freely, was considered disreputable. Then you have the kinds of dancing that they were doing, which some called sexually provocative. One of my favorite dances that was called out was called the “Funky Butt.” So that gives you some sense of the suggestiveness that these working class people freely engaged in. Employers of domestic workers were also noticeably critical of these dance halls. They saw them as standing in the way of a good work ethic. They wanted the women to spend their time after work resting, to get ready for the next day of work. And obviously, they felt entitled to tell the workers what to do outside of work, to control their bodies, for the labor that they as employers benefited most from.

Jeanne Theoharis: I think what you do in the book is also — and I think both you and Robin Kelley have been really trailblazers in showing us the kind of full range of people’s freedom dreams, that freedom is certainly having a living wage, it’s certainly having decent working conditions, it’s certainly not being sick. But if we’re going to talk about freedom, it seems like partly what you’re asking us to think about in the book is the full menu of freedom.

Tera W. Hunter: Absolutely. I mean, the title of my book is kind of a literal phrase, “To ‘Joy My Freedom,” to enjoy in all of its forms. It’s a quote from a recently freed woman whose former slave owners asks her, basically, how are you going to cope? Why would you want this? Trying to basically talk her down from her aspirations. And she’s saying, “To ‘joy our freedom,” meaning to enjoy her freedom. That’s why she wanted to be free. So, that meaning of joy and enjoyment meant, above all, autonomy. Above all, not to be treated as an enslaved person and to have all the freedoms that free people actually took for granted — to be able to work or not to work, to be able to enjoy their time in leisure activities that gave them pleasure.

Jeanne Theoharis: One of the things I write about and like to think about are the reasons we get the myths we get — and I think in the twenty years since your book was published, I think the teaching of Reconstruction and the era after Reconstruction has certainly gotten a lot better. One of the things I wanted you to talk to us about is what you think some of the myths that still remain, the misimpressions, some of the problems in the ways that we imagined Reconstruction and the period after Reconstruction. And then why you think those are there, because again, just like the political uses of a myths we still have about that era.

Tera W. Hunter: I would love to hear from the teachers about this, to get an up-to-date view on what’s being taught, what’s not being taught. But I still don’t think that we fully appreciate the monumental moment that Reconstruction represents. Du Bois called it “a splendid failure.” Part of what made it splendid is that Reconstruction engaged the broad participation of recently freed people in political mobilizations that were designed to make freedom and democracy real. African Americans were active participants in efforts to secure the vote, to run for office, to use their collective power to help America live up to its ideals, those ideals outlined going back to the Declaration of Independence. And they fought for rights not just for themselves, but for everyone.

So, one of the things that is a sign of this is that they supported public education. They were among the biggest proponents of providing public education in the South, making free schools open to all, which before Reconstruction did not exist. One of my favorite articles that captures some of these issues is written by Elsa Barkley Brown, and it’s about the Black public sphere [“Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom,” Public Culture, Fall, 1994]. It’s about Richmond, Virginia, and she allows us to see what was happening at the grassroots in this particular city, with all kinds of individuals and groups, starting in the Reconstruction period and then stretching into the 20th century. We get a chance to see women and men and children, working class people, middle class people, secular organizations, religious institutions, political parties, all engaged in this period of Reconstruction and beyond and looking at some of the tensions that emerge as well around gender and class.

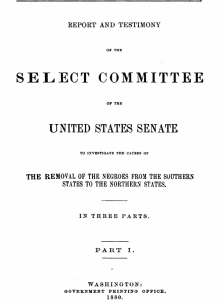

Another thing that I think is perhaps neglected still about Reconstruction is that we don’t pay enough attention to why it failed, or how it failed, and that violence was behind it. It was a deliberate effort to end Reconstruction, and it didn’t just come to an end on its own. So, political violence was a key factor in American politics, especially in the South during Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan played a very pivotal role in terrorizing African Americans, as well as white Republicans, using intimidation, destroying property, [and] assaulting and murdering African Americans and their allies, to prevent them from voting, to prevent them from participating in politics and otherwise expressing their rights. That led to a congressional investigation of these incidents, and it led to the passage of the KKK [Enforcement] Act of 1871, which was just recently referenced in a lawsuit that was filed by Representative Bennie Thompson on behalf of those like himself who were basically being terrorized by the insurrectionists on the Capitol this past January. I think that moment of violence is really important, and we have great sources to tell that story for teachers to look at. We have the congressional investigations on the KKK, literally volumes of testimony, including African Americans who took risks to go and testify about the ways in which they were being victimized.

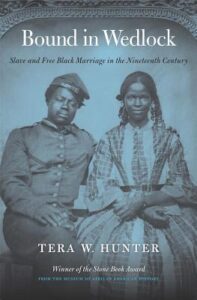

Jeanne Theoharis: So, I wanted to geek out a little bit, partly because one of my favorite talks that I heard you give many years ago when you were just starting Bound in Wedlock was a talk about sources, and in many ways, part of what you and our generation of scholars did was pushed back against this idea that there were certain histories, like those of Black marriage during slavery, that we would just never be able to know. And I think people like you, and many others, refuse to just say, “Okay, they are just things we can’t know. They’re just things we can’t study.” But what I loved about this talk was the ways that you talked about how you were going about it. I certainly know this community of teachers loves to hear about the sources, so either with Bound in Wedlock or To ‘Joy My Freedom, if you could tell us a little bit about how you move past, again, these kinds of messages that I think we, many older generation of historians had, like, “that’s an impossible story to tell, there’s not the sources.”

Tera W. Hunter: I’ll start by comparing To ‘Joy My Freedom and Bound in Wedlock because, literally, I was told that you couldn’t write the book that I wrote, To ‘Joy My Freedom, because of the lack of sources. I had to be very strategic in terms of the way that I approached the subject. When I would go to archives, I wouldn’t go and say, “Can you show me your archives on domestic workers,” because they would say we don’t have such records. So, I had to be very creative. The kinds of records that I wanted to look at, to try to find, those, often, little bits and pieces of evidence that I found in lots of different places that one would not expect to find material on Black women, especially Black women workers.

So, with To ‘Joy My Freedom, I was really having to work with a scarcity of sources. Whereas with Bound in Wedlock, I would say the opposite was the case, where I had abundance, in part, because the scope was different. Bound in Wedlock is based on the entire 19th century. It’s not regionally specific, so it covers much of the nation. It’s a much bigger, broader book, so that also left room for having many more sources. But, what’s also interesting is that I started research for Bound in Wedlock in a particular set of sources, the Freedmen’s Bureau records. When I finished writing To ‘Joy My Freedom, and I was thinking about revisions and going back and doing more research, I did some more research in the Freedmen’s Bureau records at the Freedmen and Southern Society Project at the University of Maryland. As I was going through those records, I kept coming across more and more and more about marriage and family, and I kind of put those aside thinking, “Well, maybe I’ll write an article that really kind of extends what I did in To ‘Joy My Freedom, just focusing on Reconstruction, dealing with marriage and family.” But what I ultimately decided to do was that, what those documents revealed to me was the importance of actually going backwards and looking at slavery and then also going forward and looking towards the end of the 19th century.

But, literally, I felt like I had to write about the entire 19th century to really reckon with the complexity of the records from the Freedmen’s Bureau. We have this unprecedented treasure trove of records coming from that period, freed people speaking about their experiences under slavery, as well as in freedom. And with respect to marriage and family, I felt like that complexity had not yet been reflected in the books that had been published. So, giving more texture to the emotional side of African American family dynamics, especially the emotional side of men’s lives for example, in terms of their family relationships, thinking more about how gender was a contested issue in the context of marriage. Also thinking about the importance, like how central Black families were to Black survival and how they fought tooth and nail for those families, willing to sacrifice their lives if necessary to defend those families. So all of those things encouraged me to think about going back to really reconsider slavery, and marriage under slavery, and family under slavery, and then going forward into the end of the 19th century.

Then another set of records I’ll mention, I mean, Bound in Wedlock is based on lots of different other kinds of sources: legal Records, lots of personal papers, lots of autobiographies, etc. But one of my favorite sources, aside from the Freedmen’s Bureau records, also coming from this period, though, are the Civil War Widow Pension files. These were documents that were generated by veterans. widows of Civil War veterans. The Black men who fought for the United States during the Civil War, their wives and children were entitled to pensions. In order to qualify for those pensions, they had to document their marriages under slavery. They couldn’t produce licenses because marriages were not legalized, so they had to give kind of a narrative testimony explaining the context of their relationships, how they were known as a married couple, and they would bring in witnesses to testify that they had been married, or they consider themselves married even though it wasn’t legal. So you have this rich texture of these women describing their relationships under slavery, during the Civil War. You also have cases where there are competing widows, where there’s more than one widow claiming the same man. Those were always the most interesting files. Then there’s a lot of contention because the widows were supposed to remain single in order to keep their pensions. Once they qualified for pensions they were not supposed to remarry, they were not supposed to cohabit with men. Of course they did, and then there were investigations. People who are willing to talk to investigators spilled the beans. So, all of these records are really interesting because they give us a sense of the lives of these women, dating from slavery, where they describe their relationships under slavery, during the Civil War, and at the end of the 19th century, when they’re getting the pensions and they’re defending their pensions, and going into the 20th century. For some widows, you have this long record of multiple relationships over the course of the mid-to-late 19th century and into the 20th century. These are records that are located in the National Archives. But some of them are now available; they’ve been digitized and they’re available at Ancestry.com. They’re amazing records.

Jeanne Theoharis: Please put in the chat, particularly if there were questions, as I will be checking the chat for questions. Let us know how your breakout room was, what issues you talked about. One question, as people are coming back, that we had in the chat, before we left was the question of whether these women got fired for any of their work, their labor work, their work around leisure, or their public health work, or what other sorts of punishment or sanctions they might have faced?

Tera W. Hunter: In terms of the strike, for sure, there were some people who were threatened with losing their clients. Keep in mind, the washerwomen weren’t like traditional domestic workers, they didn’t go into the homes of employers. The white families were more like clients. But yes, there were people who threatened their washerwomen who participated in the strike, that they weren’t going to patronize them. There were some of those incidents that happened.

The problem is, as historians, we’re really relying on the newspaper, so that’s really the source for the strike. They don’t give us every single detail about what happened. But there were other reprisals that were tried as well. I mean, they threatened to basically create competition for them. They were going to create this fancy commercial laundry to put them out of business. So they came up with all kinds of things to try to discourage the women from actually carrying out the strike. But not very much was effective in the short term. And in the long term, they were actually really committed to manual labor. They really didn’t want those commercial laundries, those commercial laundries, they actually lagged behind development compared to the North. In the North, they were happy to switch to machines during the war. In the South, they still wanted to have Black women perform that work.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. A couple people asked a couple different questions in the chat related to this. Did the Black press cover the strike? Also, what was the relationship between the strike and other unions, between the labor activism of elite African Americans and also other white labor unions.

Tera W. Hunter: In terms of other labor unions, there is no evidence of other labor unions supporting the strike or being against the strike. The strike did actually inspire other workers to organize though. There were waiters at a local hotel that basically had their [own] little work stoppage as a result of the strike. So, there are definitely other workers who were inspired by the washerwomen, more so than unions coming to support them.

But it was also something that was widely supported within the Black community. In terms of newspapers, we only have The Atlanta Constitution, which was the white daily, the same Atlanta Constitution there is today. But back then they made no shame about just being boldly racist, just blatantly racist in the editorials, as well as the way they reported the news.

Jeanne Theoharis: I had a question going back to public health: I wanted to hear a bit more about how the women pushed back against the stigmatization, because I think sometimes we are not so good at being able to imagine how activism doesn’t just provide it — obviously, they also were doing important things in terms of providing community services around public health — but to push back on a broader public demonization and stigmatization around TB. I guess I was just wanting to hear a bit more.

Tera W. Hunter: First of all, I think all of you are going to get a copy of my book, so when you do, you’ll see the political cartoons in the book. There are pictures of the ways in which domestic workers were caricatured for spreading tuberculosis. They’re viciously racist, just viciously racist. There are all kinds of ways in which these women were being talked about, in the newspapers, in narrative form, as well as visual representations of these women as contagents spreading germs. We don’t have a lot from the women themselves. Again, the evidence is not really there in terms of how did domestic workers themselves respond, but what we do have are the responses from African American public health experts, professionals, physicians, for example, directly challenging [and] criticizing these claims that are being made about Black women spreading disease, making the corrections about how disease actually spreads, but also just really challenging the racist assumptions behind the ideas that would say, somehow “Black women are responsible for white folks’ disease.” That’s a quote; I was trying to find the exact quote for that physician saying that, something to the effect that it seems really strange that Black women are being charged with spreading white folks’ disease. So, those were the kinds of responses that we got. It’s mainly from the people who have a platform, the professionals who have a platform to directly take on their counterparts.

Jeanne Theoharis: Last week we saw Senator Warnock give his — everyone was calling it his “maiden speech,” which I found to be a weird phrase. And he did a very powerful thing, which is that he gave the country both a sermon and a history lesson about the long history of voting rights activism and voter suppression. One of the things that I always appreciate about him is that he never mentions John Lewis without mentioning Amelia Boynton and calling out the activism of women in the Civil Rights Movement. But certainly your work helps us go even earlier. Then, on top of that, we’ve obviously been having the centennial of the 19th Amendment and a long needed conversation about the role of Black women in the struggle for the right to vote for women and in the ways that that right didn’t include everyone. So, I was hoping you could give us a bit more of that earlier history.

Tera W. Hunter: Thinking about women’s rights to vote is a really good way for studying suffrage, both as it relates to women and as it relates to African Americans. We’ve had all these conversations over the last year or so celebrating the anniversary of the ratification, that happened this past August, and I think that’s helped to call attention to the significance of voting rights for women, but also the fact that Black women were largely excluded, as were other women of color. That had to do with Jim Crow laws. The same laws that prevented Black men from voting also prevented Black women from voting. So, you have poll taxes, you have grandfather clauses, you have literacy tests. All those provisions were used in the South, especially to keep women from voting, the same way that Black men were kept out of the polls.

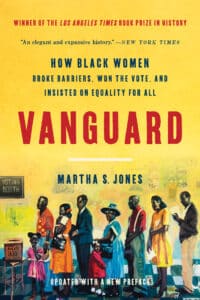

Martha Jones’s new book is great on this, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. There was someone here who was a student of Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, that he mentioned earlier in the introduction, before we got started. She was a pioneering scholar who taught at Morgan State, and she started working for women voting rights activists going back to the antebellum period. She started working on that in the 1970s. So we have this very long history stretching from the antebellum period into the 20th century, and I think it’s a great way for teachers to teach about the Voting Rights Act because you have this large timeframe. They’re great primary sources — speeches, essays, newspaper articles, memoirs — because there’s so many women. I think when Terborg-Penn did her research, she found 120 Black women up to 1920. Since then, historians have found many, many more women. Then what’s great is that a lot of these women were involved on multiple fronts, again, attacking racism, sexism, classism, all the isms, and being a part of multiple organizing efforts. Someone like Ida B. Wells Barnett, she was the leading anti-lynching advocate. She was a founder of the NAACP, she was very active in women’s organizations, she was a suffragist as well. Of course, Jeanne, your work on Rosa Parks; she was doing work in the 1940s around voting. A lot of the women that we know from the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, they started with voting rights decades earlier. So, I think we can use the history of the women’s vote to look at the ways that it intersects with the history of African American voting rights and the history of other people of color as well.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. One question we often end with is a question about, well, a couple of things — I have a whole list of things that I am frustrated that students don’t know when they get to me about the Civil Rights Movement, Black Freedom Struggle in the post war era — but I would love to hear a couple of things that maybe you are frustrated by that students don’t know that you wish they knew. And maybe, again, reasons for optimism, things that you are pleased that people now know that, again, we didn’t. Certainly there are things that also are like, “Whoa, I wish that I knew that.” But you know, before I got to college, before I got to grad school, or I got to like two years ago.

Tera W. Hunter: Well, I would say the good thing is I feel more optimistic. When I first started teaching I felt like there was so much that students weren’t learning, whereas now I feel like they’re coming with a better sense of history. So, I don’t feel like I’m always having to make up for deficits or correct misconceptions in the way that I did twenty years ago.

On the other hand, I still feel like the three areas where they still know the least, or have misconceptions about, are slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. So those three are the areas that they’re usually the most surprised by themselves when they come into class and they learn things they’ve never learned before. It completely just rocks their worlds. So those are the areas I think that need to be covered better in schools. And we see this not just in terms of college students, but we see this in the public discourse, in terms of what’s lacking, which reflects what they learned in high school, or, if they went to college, perhaps what they didn’t learn there as well.

Jeanne Theoharis: I think people want to know what you’re working on now.

Tera W. Hunter: Well, one of the things I’m working on grows out of Bound in Wedlock. Bound in Wedlock focused on the 19th century, but the epilogue jumps into the 20th century. So when I was writing about slavery and marriage, the issue that always comes up is what about things that are happening in more recent times. So I felt like I had to address that, which I do in the epilogue. Also, because there’s so many misconceptions about African American family life, about Black marriage patterns in the 20th century, and how much slavery has to do with those patterns and how much slavery doesn’t. I felt like there was no way to write a book about the 19th century without addressing the 20th century in some way. So I did that in 2the epilogue.

I’m now thinking about doing another project that looks just at the 20th century. I’m struggling a bit because I don’t want to do what I just did — I’m not going to spend another 15 years writing a comprehensive study of a century of history. So I’m thinking more episodically of the 20th century, and looking at the politics of Black families, the ways that we talk about the family, the ways that the family has been implicated in so much of public policy that we take for granted, or underestimate the role that the family plays in our public policy, and public discourse about race. Thinking about what I call the racial marriage gap, how it is that we started at the beginning of the 20th century with African Americans marrying slightly more than whites, and how we end the 20th century with that pattern reversed, with African Americans marrying significantly less than white Americans.

Jeanne Theoharis: Thank you. I’m going to bring Cierra back in a sec, but I just wanted to express my gratitude for you joining us tonight. We created this series a year ago, in many ways to create community, and the pandemic both opened up opportunities to get out of the textbook and also the need for online resources, for ways to be together and to share learning and tips. So we’re just really fortunate that you, Professor Hunter, could be with us tonight and, again, bring us back into the 19th century for some of this long Black Freedom Struggle. Thank you.

Tera W. Hunter: Thank you, I appreciate the invitation. It was fun, and I look forward to hearing feedback from the teachers.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Thank you, thank you, thank you. They both left us with so much to think about and explore. And thank you to everyone here for your commitment to learning and teaching people’s history. Thank you to our facilitators, thank you to our guests, and thank you to our ASL interpreters. We appreciate you. We’ll be sending a follow up email with the resources that were referenced here today. Thank you so, so much for joining us, thank you again Dr. Hunter for joining us, and thank you Dr. Theoharis for leading and facilitating this conversation.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Teachers can humanize movements with collective activism and stories about the strength of marginalized women.

The rules working women had to follow.

Everything. I was born and raised in Mexico so I do not know a lot of history from the U.S., but I’m learning more everyday. I want my kids who are being taught in the U.S. to learn the real history and not the whitewashed version.

Public health campaigns and how tuberculosis was characterized as a Black service worker’s disease.

The story about the neighborhood union focusing on health care issues in the Black community.

I was never taught this in school, and now that I am a teacher educator, I want to pass along information that they do not know about, or were never taught themselves, and provide them resources for the history and materials to use in their own teaching. I enjoyed hearing about the “taboo” dancing that occurred, as I am a dancer, so always interested in dance-related history.

Different strategies used by the working class to struggle for freedom beyond wage and work. I want to learn more about the Atlanta Washerwomen’s Strike.

That Black working women in the 1881 washer women’s strike were part of a long, broad movement for living wages, public education, public health.

The importance of pushing for ethnic studies K-12.

Dr. Hunter naming three things that we need to do better in high school — slavery, Civil War, and Reconstruction — thank you, so powerful and helpful!

Organizing of the washerwomen. My grandmother did this type of work in Trinidad.

I appreciated the information about the grassroots organizing of the domestic workers in Atlanta in 1881 and how that carried over to Stacy Abrams election as well.

The connecting thread running from the labor struggle of the 1800s to the 1950s.

How Black women were able to harness collective power to make changes to their working conditions.

I learned a lot about African Americans and marriage within the lens of slavery. I was not informed of a lot of those dynamics. I also appreciated the intersectional and historically framed way that Dr. Hunter shared her research today.

The primary sources: Freedman Bureau records, congressional testimony on the KKK, Civil War widow pensions etc. I learned about the washerwomen’s strike as a prereq to the class but prior to that I was not aware of this amazing organizing done so early after the Civil War

Black women were organizing Domestic workers in the 19th century. Before I thought of domestic worker organizing as a recent phenomenon, but this struggle goes far back and it was often people of color led in this country.

I appreciated the way Dr. Hunter creatively thought about which sources could help her craft the story she was telling about the washerwomen’s strike and the loving relationships among formerly enslaved individuals.

The connection between stigma around COVID for the AAPI community today and the similar experience of Black folx being labeled as the primary vector for spreading TB in the early 1900s piqued my interest and definitely illuminated some simple ways to make connections in the classroom.

The Washing Women Strike in 1881, the idea of “broadening leadership possibilities” by the means of organizing in “cells” in Lugenia Burns Hope’s Neighborhood Unions, and the inclusion of “leisure” to bring the full picture of domestic workers’ lives to life.

Didn’t know about the three washerwoman strikes — 1860s, ’70s, ’80s — such different decades in relation to Reconstruction. Makes me want to learn more.

Neighborhood Association was an important discovery. It helped me gain a wider view into modern coalition building that we see today.

What will you do with what you learned?

Adapt my lessons to include more archival research.

I am trying to integrate more primary sources into my English class to go with novels, poems, etc. so I think there are a lot of materials I will look at integrating here.

I’m purchasing Tera’s book so that I can read and learn in context. I am passing this info on to my colleagues who teach middle and high school and growing my “Backpack” of tools for my 4th-grade class.

Lessons looking at jobs that are deemed menial, unskilled, or looked down on and how that is racialized, gendered, and demeaned. The history of how these workers fought for economic justice.

Make more explicit the connections between the 19th century and the 21st.

I’ll connect it to the current organizing by women of color for One Fair Wage.

I’m doing research on my family’s history and writing about it. This info helps me think about my grandmother’s working conditions and the legacy of Black women’s organizing.

I teach kindergarten so I’m continuing to grow my own history so I can figure out what and how to bring it to my little people.

I’m a math teacher and looking forward to incorporating the various collective action movements (washerwomen’s strike, public health campaigns, etc.) into my lessons. I’m imagining some analysis of economic impact from the strike and/or a data visualization challenge to have students create graphs that explain the impact of the strike.

Looking forward to having a chance to bring this history into my classroom; not sure where it will fit yet as just designing courses for next year, but excited to possibly bring into a critical ethnic studies course focused on labor and justice issues.

I am on the curriculum subcommittee of our Cultural Competency Committee and I will be making recommendations about content that needs to be included and/or revised.

I’ll include some of it in my discussions with my students about sociology and the background to many of today’s social developments and movements.

I am thinking about building inquiry stations around a variety of strikes and uprisings that will demonstrate people standing up for unfair work conditions. This would be for students to explore on their own and then share back with the groups. We would also weave in conversations about minimum wage and other situations here in Chicago that have been in the current news.

I am a student of power and power inequality. As a cultural anthropologist, I have focused most of my life work on activism and community education. Am working hard right now to read/listen/learn more about Reconstruction and the decades after. Sharing this history needs to be woven into all kinds of daily interactions, not only in classrooms. That’s what I try to do — with adults, youth, children — our histories are powerfully with us and active in our daily interactions.

As a Pre-Service teaching instructor at an after school program, I often inhabit the middle place on what parents may not be aware of our what schools will not teach since Indiana’s history curriculum is so incredibly lacking. I hope to incorporate these materials for teachers to work with our students with to help widen their perspective on historical events post Civil War and beyond.

Learn more! Follow recommended reading, continue asking hard questions and also remember to find beauty in the struggle. Research more about women’s history, class and race — in the U.S. and beyond.

What did you think of the format?

Loved an opportunity to connect with others in breakout rooms.

I continue to marvel at how well this is organized: clear, lucid, supportive, respectful, generative.

It was short, but it gives me time to process and plan for next steps in my curriculum.

Format was great. I love the way you introduce the sessions, and that there is a short break out, which just is nice to see and be able to chat with people from across the country. It makes me feel like we are all in this truly together. Also, the explanation of the politics and pedagogy of the breakout room is so well-explained. Thank you.

The format continues to be great for learning and reflecting!

Loved having breakout rooms to process the first part of the sessions! Perfect amount of time in breakout rooms and perfect sized room (our room had 5 people). I did wish the whole session had been a little longer, maybe to have time to jump back in breakout rooms at the end or just to hear a little more from Dr. Hunter.

I always want more breakout time, because all the participants have so many experiences to tell us. People’s history happens on all levels for real.

I love how you guys utilize live participant interaction so it’s not strictly a lecture.

I thought the entire meeting worked well. We were engaged, we were encouraged to chat, we had an opportunity to exchange ideas in a breakout room, and we were allowed to submit questions to Dr. Hunter.

It all worked. I just wish I would have read the book before. Now I am reading the book from the last session on. March 8 — I figure I will catch up sooner or later!

Great facilitator (Bill Bigelow) able to allocate time for everyone’s voice to be heard.

Additional Comments

I’m encouraged by how scholars like Dr. Hunter are drilling down on lesser-known aspects of our history.

Wonderful resource. I’ll help spread the word. I’m afraid too many people who would take advantage of this resource are unaware it exists.

Thank you again for all the work to make this happen. I worked with Dr. Hunter when she came to work with students in the Newark (NJ) public schools about 10 years ago and it was great to be with her again.

Thank you so much for these fabulous conversations. I always learn so much and come away feeling more optimistic and proud.

Breakout room 20 was a little quiet but all of us were able to share and find common interests! Several group members mentioned how wonderful it was to hear from Dr. Hunter, since we as teachers have seen her in some of the Teaching Hard History videos from Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance) — it is always nice when historians share their work publicly.

I thought this was very useful and did not, like many things for teachers, pander. It was like being part of a discussion.

I have attended several sessions and each one has left me in awe. One for the scholarship that is out there but I have not been exposed to as of yet and the diversity of the groups. This is such a great way to start my week. I feel energized.

Really enjoyed doing a deeper dive into this important history. Reinforces that there are SO many elements of Black history that we don’t know or teach.

Once again, the Zinn Education Project does not fail. My son used to read Zinn history book in high school, and under-informed and/or under including teachers used call my home. They were challenged to expand their scope and my son would not need to do their work. The calls soon stopped.

I hope the idea of doing Zoom presentations and workshops continues after the pandemic. Very accessible for me with my time, energy during the school year.

It always amazes me that enslavers really couldn’t believe the enslaved would want to leave them (and the idea of “freedom” was totally beyond their comprehension). The book’s title is gorgeous. And the story behind it is so revealing: that a former enslaved woman responds that she wants to “Joy My Freedom” when her former enslaver asks why she’s leaving. It reminded me of the fact that enslavers made up a name for an illness that they said the enslaved caught, which is the reason they ran away. I mean, why else would they try to escape?

I really appreciated the high quality of engagement in the key conversation — it was a lot more significant than simply mentioning women’s names to include in a learning plan.

Dr. Hunter brought up important issues that are essential for our deeper understanding of history and yet not discussed very often. Dr. Hunter’s perspectives were enlightening.

I am impressed with the diversity of people who attended. My group had 7 people from all parts of the U.S. and one from Canada.

Presenters

Tera W. Hunter is an award-winning scholar of labor, gender, race, and Southern history. She is presently a professor of history and African-American studies at Princeton University and the author and editor of several books, as well as a contributor to public intellectual life through her consulting with museums, classroom history education programs, and documentary film.

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition, and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow at Teaching for Change through the Communities for Just Schools Fund. As a Ph.D. student, her work examines how Black girls use arts-based practices (such as movement and music) as forms of expression, resistance, and identity development

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn