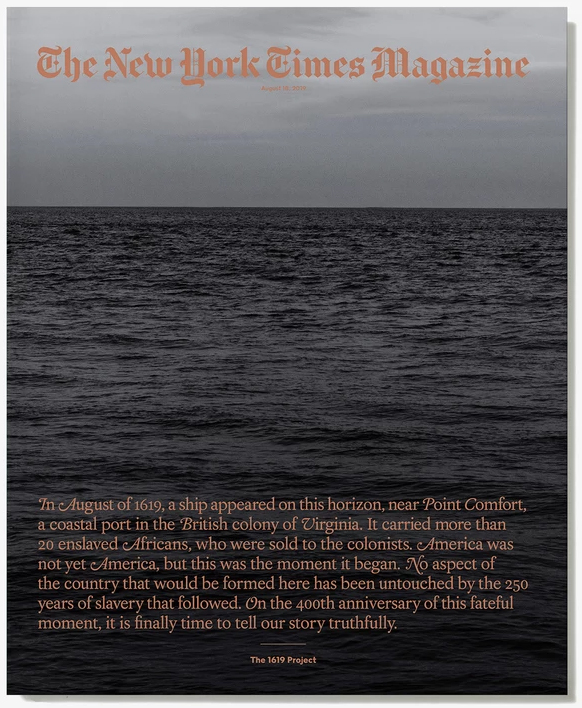

In August, the Zinn Education Project team, like many educators in our network, scrambled to get copies of the New York Times 1619 Project.

In August, the Zinn Education Project team, like many educators in our network, scrambled to get copies of the New York Times 1619 Project.

The multiplatform effort by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and The New York Times highlights the fundamental role slavery played in the United States’ development by commemorating the year in which the first enslaved Africans were brought to the new Virginia colony.

Featuring essays on slavery’s intimate entanglement with U.S. capitalism, health care, politics, cities, food, and music, as well as poetry and fiction by Clint Smith, Jesmyn Ward, Eve L. Ewing, and others, the 1619 Project persuasively affirms that the consequences of slavery — and the contributions of Black people — should be central to any story the United States tells about itself.

We agree.

Teaching Resources on 1619 Project Themes

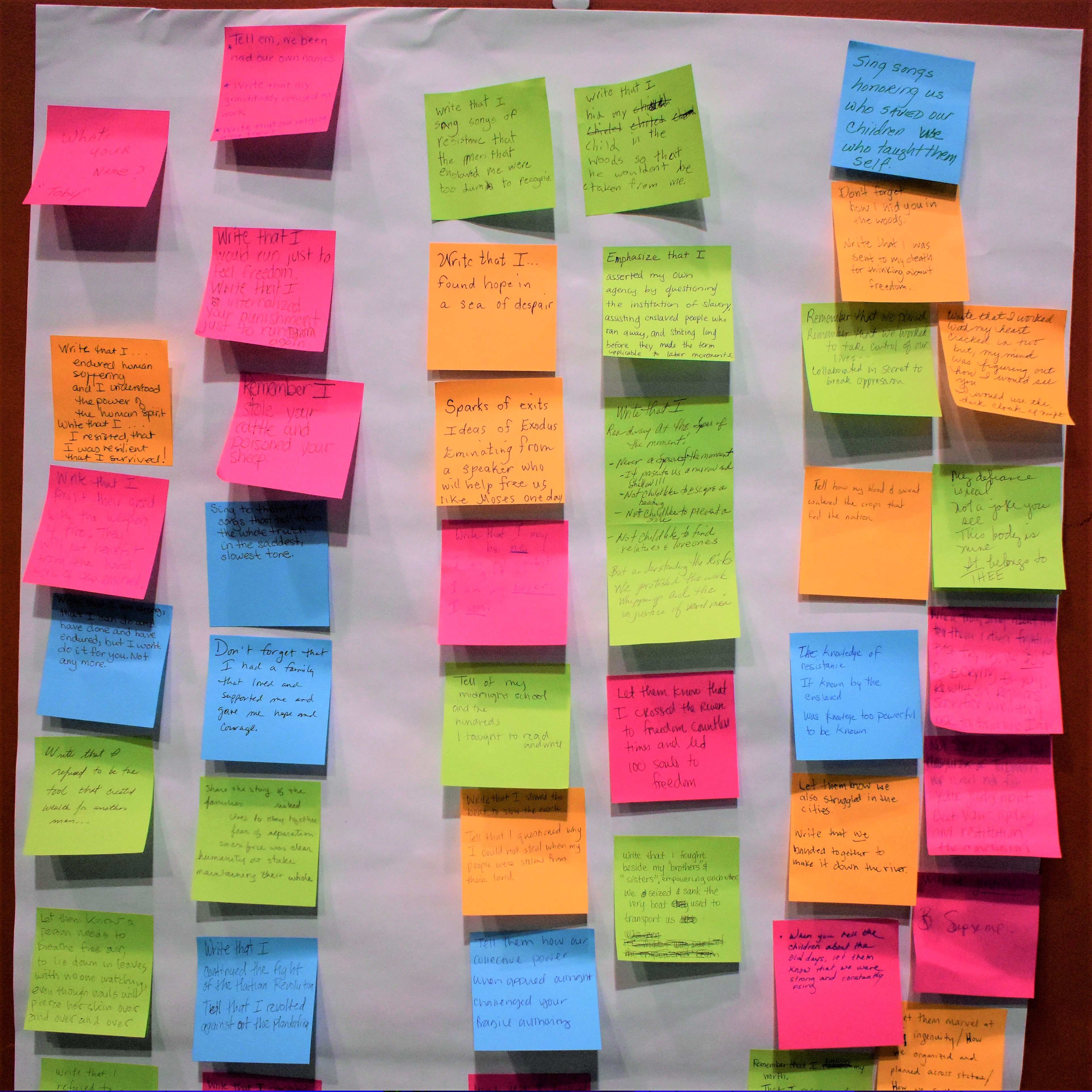

Below you will find several classroom-tested people’s history lessons and articles on slavery’s central role in U.S. history, its legacies, and the activists who ended it.

- In The Color Line lesson, investigate how social elites encoded racial division in colonial laws to divide people who, if acting collectively, might threaten the status quo.

- Through role-play, upend the traditional narrative of the Constitutional Convention by including the perspectives of workers, enslaved people, and poor farmers, alongside those of the real participants — the white wealthy elite.

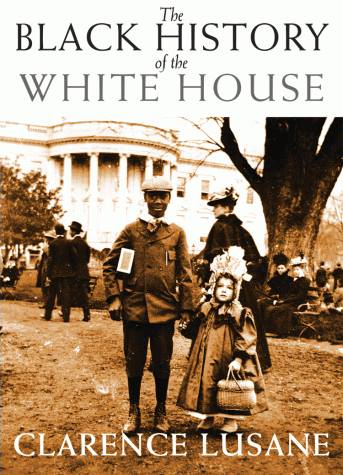

- Ask students to grapple with the startling fact that more than one in four U.S. presidents were involved in human trafficking and slavery as Clarence Lusane explains in this If We Knew Our History column.

- In The Poetry of Defiance, surface the many ways — creative, brave, bold, subversive, everyday, and extraordinary — that enslaved people resisted their own subjugation.

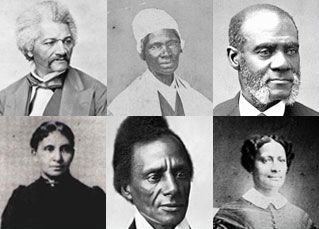

- Bring to life the politics of anti-slavery and Reconstruction by asking students to consider both the dilemmas faced and radical possibilities carved out by activists during the 19th century. Critical to both of these efforts were Black abolitionists.

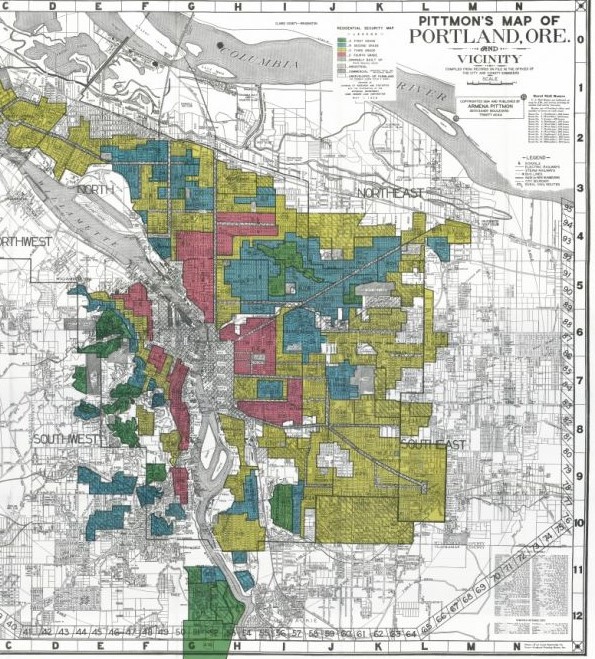

- The 1866 Civil Rights Act intended to prohibit policies that perpetuated the conditions of slavery for African Americans; it said that formerly enslaved people had the right to “purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.” Yet, this lesson, based on Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America shows how government policies denied African Americans their constitutionally protected rights to fair housing and segregated every major city in the United States.

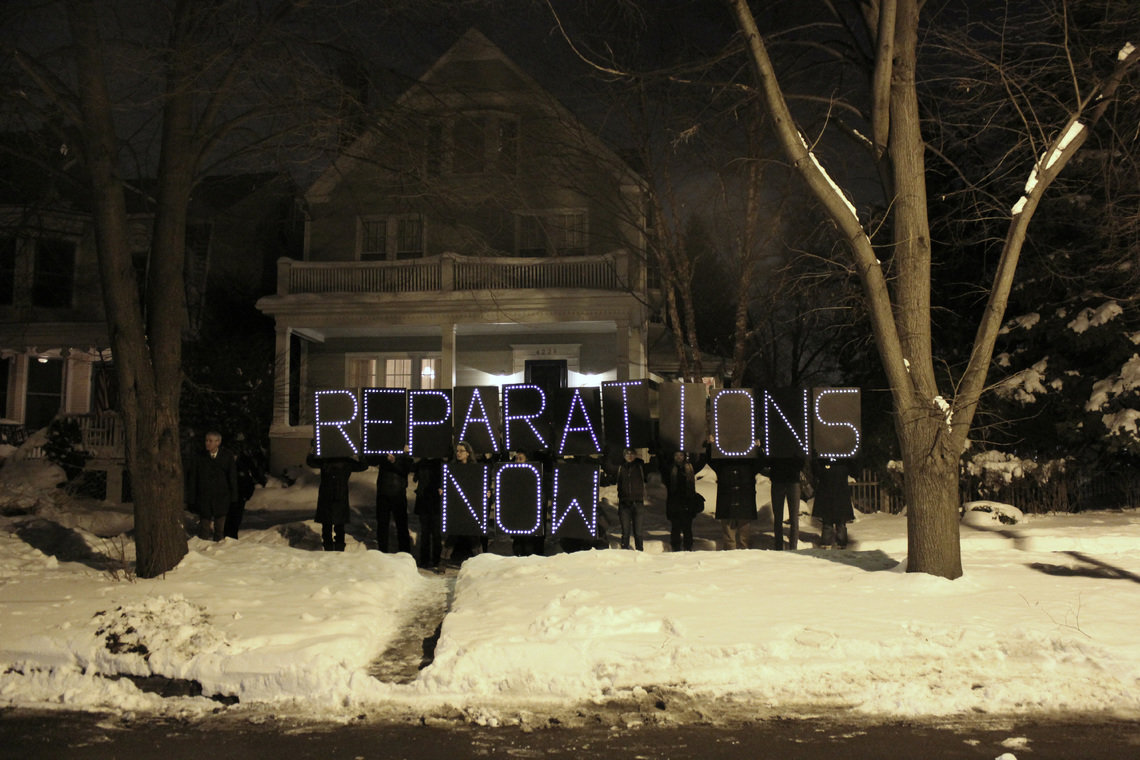

- In How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations students examine more than a dozen different reparative policies to help clarify their own beliefs about the appropriate context, goal, and form of reparations for historical injustices like slavery and genocide.

Demanding reparations for police torture, members of the Chicago Light Brigade, Project NIA, and Chicago Torture Justice Memorials protest outside of Rahm Emanuel’s home in 2015. Source: Kelly Hayes.

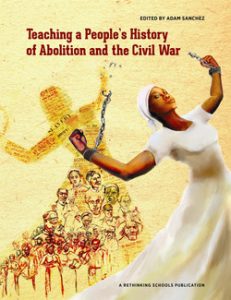

Rethinking Schools’ newest book, Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War, edited by Adam Sanchez, encourages students to take a critical look at the popular narrative that centers Abraham Lincoln as the Great Emancipator and ignores the resistance of abolitionists and enslaved people. The book’s classroom-tested lessons help students understand how ordinary citizens — with ideas that seem radical and idealistic — can challenge unjust laws, take action together, pressure politicians to act, and fundamentally change society.

Teaching Resources on Gaps in the 1619 Project

The 1619 Project has invigorated the ongoing conversation about the central role of the institution of slavery in U.S. history and its legacy today. Let’s keep the conversation going by filling the gaps of what the Project does not address:

- When teaching about the enslavement of Africans, it is vital to start with pre-colonial African history. Our colleagues at Africa Access provide a carefully vetted list of books and other resources.

- Although 1619 marks the first arrival of enslaved Africans in the English speaking colonies, their presence in what is now the United States began much earlier as is explained in “The Fallacy of 1619: Rethinking the History of Africans in Early America” by Michael Guasco. He also adds that it is important to remember that the English were also newcomers. “Elevating 1619 has the unintended consequence of cementing in our minds that those very same Europeans who lived quite precipitously and very much on death’s doorstep on the wisp of America were, in fact, already home. But, of course, they were not. Europeans were the outsiders. Selective memory has conditioned us to employ terms like settlers and colonists when we would be better served by thinking of the English as invaders or occupiers. In 1619, Virginia was still Tsenacommacah.”

- The 1619 Project describes slavery as America’s original sin. That is true. But it wasn’t the only one. There was also the closely related sin of the genocide and removal of Native American nations, a history that is closely intertwined with the history of slavery in the United States. For example, the vast lands of cotton and tobacco plantations were only “available” because of the forced removal of Native Americans. Students can learn about that history with the lesson, The Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play.

Professor Greg Carr.

Critical Questions About the 1619 Project

Professor of Africana Studies at Howard University, Gregory Carr, rightly highlights that the Project’s 1619 origin story for Black history shapes what is asked, investigated, and learned. On Twitter, Carr quoted historian John Henrik Clarke: “If you start your history with slavery, everything since then seems like progress.”

In a recent WAMU podcast on the effect of the 1619 Project on how slavery is taught in the classroom, Carr elaborated some of the limitations he sees in both the point of departure and the scope of the 1619 Project. He said:

It isn’t necessarily revolutionary to move from say 1776 to 1619. It still centers the kind of English presence in North America, when we know, of course, that Africans had been brought to North America as enslaved people by the Spanish over a century before. And I think that there’s a bit of a sensationalist turn when you say you’re rewriting the history of America when in fact you’re reinscribing for me a very troubling and problematic framework. And that troubling and problematic framework really I can reduce it down to a word, citizenship. What does it mean to have a contemporary society where to be a citizen makes you more human than people who aren’t? This idea, for example, that the enslaved Africans would look forward to a day when they would become citizens was really absurd if you just look at history.

When you say, for example, that these contemporary us, these contemporary African people in this country are our ancestors wildest dreams, well, all you have to do, a quick glance through history will show that, no, their wildest dreams were to escape. More Africans fought for the British or ran away than fought for George Washington’s army, for example. Their wildest dreams were to return to Africa for those first generations. Their wildest dreams were to be left alone.

So the 1619 Project is important in certainly having us have these conversations. But it is by no means at the center of or in any way really superior to the work that had been done by Black and brown journalists, writers, historians. Go back and look at any ten-year period in Ebony Magazine from its founding up through recently, you’ll see its better in some ways, more insightful and certainly differently framed curriculum work. And that’s just been going on incessantly. And what I’ve learned in terms of curriculum over the last 25-30 years of teaching and curriculum writing is the right answers rarely exist. But the right questions can always be asked. And I don’t think the 1619 Project asks right enough questions.

“Original sin” of settler colonial states like US is genocide on people then living in now-imagined “countries.” The deepest “reconceptualizing” work will be to displace “citizenship” as prerequisite for full social equity. Otherwise, it’s a fight for inclusion in settler dreams.

— Greg Carr (@AfricanaCarr) January 25, 2020

Support Teaching People’s History

The 1619 Project’s insistence that enslaved people’s lives and contributions be centered in the U.S. narrative matches the Zinn Education Project approach to history which emphatically affirms: ordinary people matter. However, as Carr points out, highlighting ordinary people is not enough — students need to examine how their lives are framed.

Help us continue to offer free people’s history curriculum that counters the inaccurate and dangerous corporate textbook version of history.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn