On Dec. 7, 1874, the Reconstruction era “Vicksburg Massacre” occurred in Mississippi, with estimates ranging from 75 to 300 African Americans killed. Whites attacked Black citizens who had organized to defend Peter Crosby. Formerly enslaved and a veteran of the Union army, Crosby had been forced to resign from his elected role as sheriff.

On Dec. 7, 1874, the Reconstruction era “Vicksburg Massacre” occurred in Mississippi, with estimates ranging from 75 to 300 African Americans killed. Whites attacked Black citizens who had organized to defend Peter Crosby. Formerly enslaved and a veteran of the Union army, Crosby had been forced to resign from his elected role as sheriff.

Read a detailed description of the massacre in an excerpt from A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration by Teach Reconstruction campaign adviser and historian Steven Hahn.

Most important was the emergence of the White League and of the “White-Line” movement more generally, in Louisiana and Mississippi. Committed to drawing the racial “line” in politics and inviting “all white men without regard to former party affiliations” to “unite,” the league was first organized in Opelousas in late April and then spread very rapidly.

Most important was the emergence of the White League and of the “White-Line” movement more generally, in Louisiana and Mississippi. Committed to drawing the racial “line” in politics and inviting “all white men without regard to former party affiliations” to “unite,” the league was first organized in Opelousas in late April and then spread very rapidly.

It clearly built on foundations established by the Klan and the Knights of the White Camelia — a Union army commander regarded the league as a “second edition of the White Camelia campaign of 1868” — but was even more directly aligned with the Democratic party. Indeed, leagues were often little more than local Democratic clubs converted into paramilitary companies. “If the democratic party is arrayed against the negro and the republicans,” the Opelousas Courier proclaimed, “it becomes a White League, and no one can object to its efficient organization.”

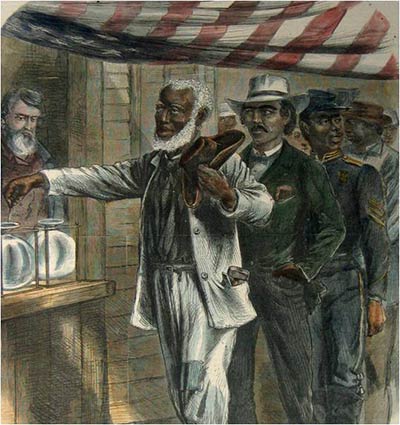

White Leaguers surely recognized that the federal government was losing interest in interfering in southern politics and sustaining Republican regimes by military means. But they also responded to the growing assertiveness of African Americans within the Republican party, which showed itself in the rising incidence of Black office holding.

By that time, too, White-Line counterparts in Vicksburg, Mississippi, had demonstrated how paramilitary mobilization and “very definite intimidation” could bring electoral success even where Black voters held decided numerical sway.

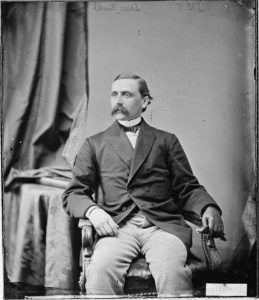

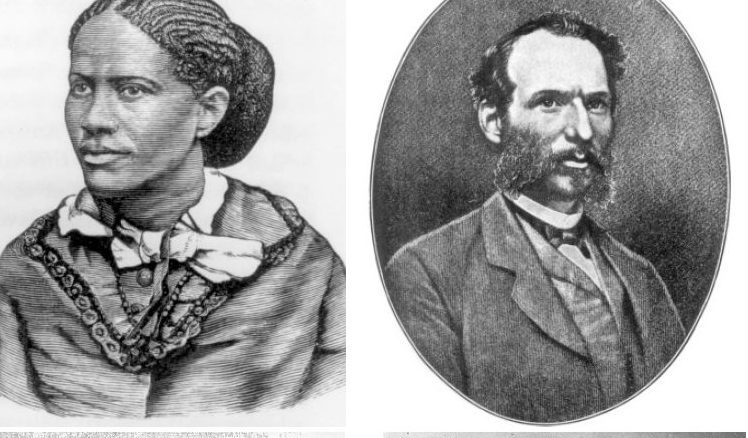

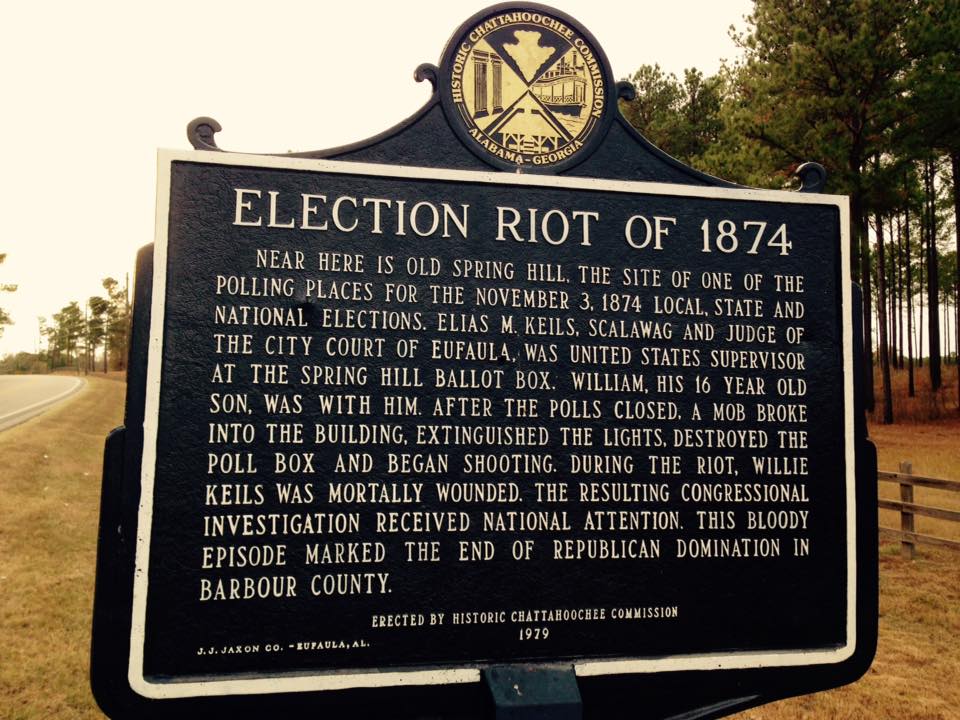

If anything still held back a full-scale white paramilitary offensive, it was removed when, in the November elections of 1874, congressional Democrats won control of the House of Representatives for the first time since southern slaveholders had rebelled against the national government. In Vicksburg, White-Liners seemed to commemorate the event by moving quickly to complete the work they had begun in the summer. This time, they focused on the county, rather than the municipal, government, which was almost wholly dominated by Black Republicans, including the sheriff Peter Crosby, a native Mississippian who had served in the Union army during the war. Meeting in early December, they demanded the resignations of all the Black officials and pressured Crosby to yield under what he regarded as thread of assassination. Crosby then headed to the state capital for help.

Republican governor Adelbert Ames, of the party’s radical faction, turned a sympathetic ear. He ordered the “riotous and disorderly persons” who had “expelled from office the legally elected sheriff” to “disperse and retire peaceably” and “submit to the legally constituted authorities.” He also instructed a Warren County militia company to “cooperate” with Crosby’s effort to “regain office” and “suppress the mob,” and suggested that Crosby should summon a posse for further assistance.

Republican governor Adelbert Ames, of the party’s radical faction, turned a sympathetic ear. He ordered the “riotous and disorderly persons” who had “expelled from office the legally elected sheriff” to “disperse and retire peaceably” and “submit to the legally constituted authorities.” He also instructed a Warren County militia company to “cooperate” with Crosby’s effort to “regain office” and “suppress the mob,” and suggested that Crosby should summon a posse for further assistance.

Ame’s orders did little to change the behavior or temper of the Vicksburg whites, but Crosby’s call for a posse revealed a strong foundation of loyalty and organizational readiness among African Americans in the surrounding countryside. With dispatch, owing to the churches, political clubs, and other institutions of Black community life, a major mobilization took place. As several hundred Blacks marched in three columns toward Vicksburg, even Crosby feared the consequences and tried to turn some of them back. It was too late. Whites opened fire, and despite some brief standoffs, the Blacks were forced to flee. For another ten days, some of the young white participants, joined by reinforcements from across the river in Louisiana, stayed on “the war path.”

When the smoke cleared, at least twenty-nine African Americans had been killed and a great many more had been wounded and terrorized. The seat of county government remained in the hands of the White-Liners. And Peter Crosby, briefly held prisoner, was compelled to resign yet again.

Ames called the state legislature into special session and together they succeeded in convincing Grant to send a company of federal troops to quell the disturbances in Vicksburg and reinstall Crosby as sheriff. But Crosby’s days in office were numbered and so too, it appeared, were those of Republicans over much of the state. For the several-month White-Line campaign in Vicksburg and Warren County amounted to a “rehearsal for redemption” in Mississippi.

Torchlight processions, paramilitary drilling, the disruption of Republican political meetings, the harassment of Black workers, the intimidation and assassination of Black leaders, the driving off of local officeholders, and the disabling of armed Black resistance — all of which made their appearance in Vicksburg in 1874 — were to come into concerted use in 1875 in counties that previously had “safe” Republican majorities.

This was one of many massacres in U.S. history. Many of the massacres, such as this one, were designed to reassert white supremacy during Reconstruction.

Find resources below to teach about Reconstruction, reparations, and the long history of voter suppression by white supremacists.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn