The once forgotten, now famous New York newsboy strike of 1899 started on July 18 when newsies in Long Island City, Queens, caught the Evening Journal deliveryman selling them short bundles. They tipped over his wagon, chased him up the street, and triumphantly carried off armloads of papers, inspiring what nearly became a children’s general strike.

Over the next two weeks boys in all five boroughs, and in cities and towns throughout the northeast, refused to sell William Randolph Hearst’s Evening Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, the two largest circulation newspapers in the nation. Their actions emboldened newsboys as far away as Cincinnati, Ohio, Lexington, Kentucky, and Nashville, Tennessee — and bootblacks and messengers in other cities — to stop work and demand better terms from their own bosses. Far from aberrations, these strikes capped a decade of discontent in the newspaper trade.

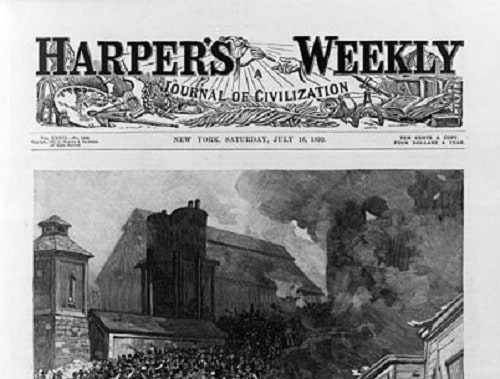

B. West Clinedinst, “The Hottest Strike of Midsummer. The newsboys of New York, who struck against the price charged by some of the one-cent newspapers, attacked the men who took their places and destroyed the boycotted newspapers–Scene on Frankfort Street, near Newspaper Row,” Leslie’s Weekly, Aug. 12, 1899.

Time was ripe for a showdown. The revolt in Queens rekindled the boys’ discontent over price hikes imposed on them by Hearst and Pulitzer at the start of the Spanish-American War in 1898. It also coincided with a national strike wave, a local heat wave, and a militant protest by streetcar motormen in Brooklyn and Manhattan that kept police tied up. Many working-class children — boys and girls — blocked tracks with debris and threw stones at nonunion drivers. Redressing grievances about paying wartime prices for peacetime papers gave newsies the chance to mobilize on their own behalf.

Three hundred of them met in City Hall Park on July 19 and pledged to strike if their demands weren’t met. “Go ahead and strike,” said the World’s circulation manager. Following the example of adult trade unionists, the boys elected officers, formed a discipline committee, and sent envoys to spread the word: “Ye don’t sell no more World ’r Joinal ’r ye git yer face punched in — see?”

Most of the boys thus approached “saw.” Newsboys refused to handle the “yellow kid” dailies from Wall Street to Harlem, Brooklyn to the Bronx, and in the Staten Island towns of Clifton, Stapleton, and Tomkinsville. Newsboys also honored the strike in the Westchester County communities of Yonkers, Mount Vernon, New Rochelle, Mamaroneck, and White Plains, and upstate in Troy, Saratoga, and Rochester.

Garden State newsboys joined in as well, starting with Jersey City, Hoboken, Newark, and Plainfield, then spreading to Bayonne, Trenton, Paterson, Elizabeth, and Asbury Park. New Englanders extended the boycott to New Haven, Norwalk, Danbury, and Hartford, Connecticut, and to Providence, Rhode Island, and Fall River, Massachusetts.

The strikers represented the full range of ages, ethnicities, and disabilities found in the news trade. Kid Blink (legal name Louis Balletti), the red-haired spokesman for the strikers in New York, was a charismatic 18-year-old Italian American with a bum eye. Dave Simons, also 18, was a Jewish boxing champion in the 105-pound class. Brooklyn’s leaders included the Irish duo of “Race Track” Higgins, an adult, and “Spot” Conlon, aged 14.

Archival Footage

To get an idea of what work looked like for the newsies, here is a clip from 1899. As described by the Library of Congress, it shows a group of about fifty pre-adolescent boys running and crowding around a one-horse paneled newspaper van. On the side of the van is a sign reading New York World. As they gather around the rear of the vehicle, a fight breaks out between two of the boys. The film ends as the crowd forms around the two fighters.

Source: (1899) Delivering Newspapers. United States: American Mutoscope and Biograph Company. Library of Congress.

African American “Black” Diamond was elected to the Manhattan strike committee, and a kid known only as “Black Wonder” held strikers spellbound with his speeches at the Brooklyn Post Office. “Crutch” Morris served on the executive committee in New York, and “Blind” Huber cochaired the “consultation of war” held outside the ferry building in Hoboken. Few girls sold papers or participated in the strike, however one little Park Row “Joan of Arc” was credited with driving off two big strikebreakers whom the boys had failed to subdue.

The struck newspapers didn’t publish a word about the strike, but the other papers ran articles and illustrations detailing the skirmishes, mass meetings, and negotiations, always quoting the newsboys in their signature slang. “Wese uns has got ter stand by one another dese times,” a striker named Billy told the Jersey City Evening Journal, “’cause if we don’t sure’s hell we’ll git it in de neck from dem capitalists.”

The struck newspapers didn’t publish a word about the strike, but the other papers ran articles and illustrations detailing the skirmishes, mass meetings, and negotiations, always quoting the newsboys in their signature slang. “Wese uns has got ter stand by one another dese times,” a striker named Billy told the Jersey City Evening Journal, “’cause if we don’t sure’s hell we’ll git it in de neck from dem capitalists.”

Although portrayed by the press in comic fashion, strike violence was no joke. Some scabs wielded table legs and carried revolvers; one forced a loaded gun down Kid Blink’s throat. The strikers played rough, too. They armed themselves with horseshoes, baseball bats, barrel staves, and wheel spokes. “Yer clubs ain’t meant for toot’picks,” “Spot” Conlon told them.

On July 24, the newsboys held a mass meeting at the New Irving Hall on Broome Street. A capacity crowd of two thousand packed the place, while another three thousand boys remained outside. Kid Blink reminded them of their victory in 1893 against the World’s no-return policy, and urged them to “stick together like plaster. Ain’t that 10 cents worth as much to us as it is to Hearst and Pulitzer, who are millionaires? Well, I guess it is. If they can’t spare it, how can we?”

The struck papers had experienced an estimated 20 percent drop in sales and much lost advertising revenue. Desperate to break the strike, circulators managers asked Salvation Army lasses to sell the two papers, but the girls refused to break the boycott. The publishers then tried to buy off strike leaders for $300 to $600 apiece. They appeared to succeed when Kid Blink and Dave Simons showed up on Park Row on July 26 with bundles of Worlds and Journals, saying they had negotiated a settlement. Kid Blink sported a new suit and unwisely flashed a roll of bills. The strike committee put the pair on trial. Both escaped conviction but were removed from office.

On July 27, the World and Journal offered to sell papers to the boys at 55¢ per hundred, but the union rejected the compromise. Defections increased, and two days later the papers agreed to accept the return of all unsold copies. The strike ended in New York on August 1 without meeting or vote and limped to a close a few days later in New Jersey. We might have gotten more, one newsie explained to a customer, but “de leaders was bought off.”

The strike had lingering consequences for both sides. Hearst felt betrayed by his fellow publishers and withdrew from their association. He and Pulitzer agreed to fix the price of their daily and Sunday offerings and establish their own return policies. The newsboys’ union continued under an adult president who advocated wearing union badges and affiliating with other labor organizations.

Their first action, decided August 13 at a mass meeting of two thousand newsies in Teutonia Hall on the Lower East Side, was a pledge not to sell copies of the New York Sun until the paper took back its locked-out printers. The next week two hundred newsboys brought up the rear of a solidarity parade. The boys waved flags and carried banners affirming their support for their union brothers.

This entry is by Vincent DiGirolamo, professor of history at Baruch College and the author of Crying the News: A History of America’s Newsboys.

Learn More

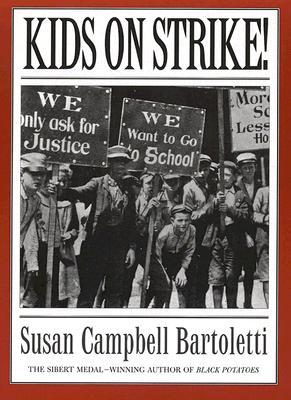

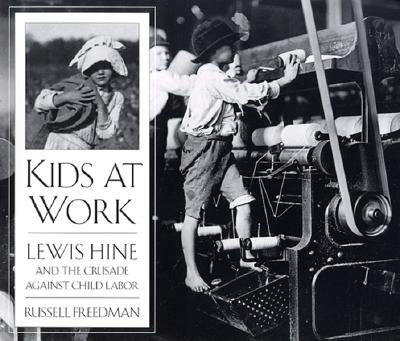

See the resources below for teaching about labor history, including 2oth century photos by Lewis Hine of newsies and other child laborers.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn