With current demands to remove President Woodrow Wilson’s name from schools and other institutions, a lot of people are wondering — why Wilson? They understood the removal of Confederate statues and building names, “but what did Wilson do wrong?” One look at textbooks’ silence about Wilson’s racist policies and we can see why many people are surprised, as James Loewen explains in Lies My Teacher Told Me. We share here an excerpt from Loewen’s book that begins with references to Wilson’s racist foreign policy in Mexico, Haiti, Vietnam, and other countries. It goes on to describe Wilson’s domestic policies, including segregating the federal government, removing African Americans from posts around the country, and contributing to the racist fervor that encouraged the rebirth of the Klan. Loewen contrasts this history with the benign textbook narrative.

By James Loewen

Textbook authors commonly use another device when describing our Mexican adventures: they identify [Woodrow] Wilson as ordering our forces to withdraw, but nobody is specified as having ordered them in! Imparting information in a passive voice helps to insulate historical figures from their own unheroic or unethical deeds.

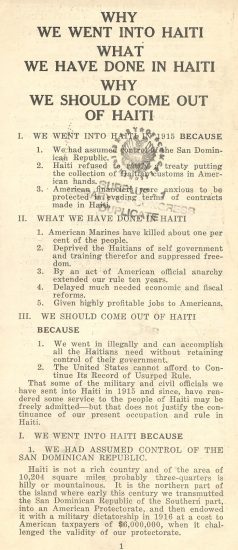

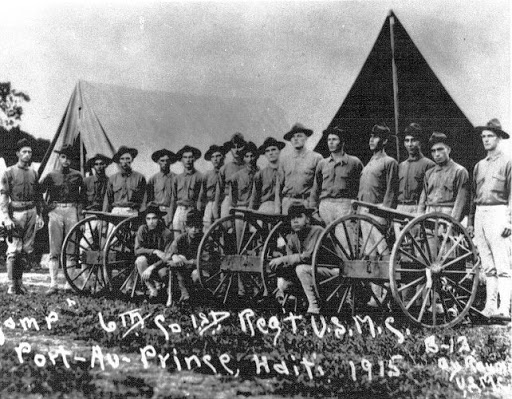

Some books go beyond omitting the actor and leave out the act itself. Half of the textbooks do not even mention Wilson’s takeover of Haiti. After U. S. marines invaded the country in 1915, they forced the Haitian legislature to select our preferred candidate as president. When Haiti refused to declare war on Germany after the United States did, we dissolved the Haitian legislature. Then the United States supervised a pseudo-referendum to approve a new Haitian constitution, less democratic than the constitution it replaced; the referendum passed by a hilarious 98,225 to 768.

As Piero Gleijesus has noted, “It is not that Wilson failed in his earnest efforts to bring democracy to these little countries. He never tried. He intervened to impose hegemony, not democracy.”

As Piero Gleijesus has noted, “It is not that Wilson failed in his earnest efforts to bring democracy to these little countries. He never tried. He intervened to impose hegemony, not democracy.”

The United States also attacked Haiti’s proud tradition of individual ownership of small tracts of land, which dated back to the Haitian Revolution, in favor of the establishment of large plantations. American troops forced peasants in shackles to work on road construction crews. In 1919 Haitian citizens rose up and resisted U.S. occupation troops in a guerrilla war that cost more than three thousand lives, most of them Haitian.

Students who read Pathways to the Present learn this about Wilson’s intervention in Haiti: “In Haiti, the United States stepped in to restore stability after a series of revolutions left the country weak and unstable. Wilson . . . sent in American troops in 1915. United States marines occupied Haiti until 1934.” These bland sentences veil what we did, about which George Barnett, a U.S. marine general, complained to his commander in Haiti: “Practically indiscriminate killing of natives has gone on for some time.” Barnett termed this violent episode “the most startling thing of its kind that has ever taken place in the Marine Corps.”

During the first two decades of this century, the United States effectively made colonies of Nicaragua, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and several other countries. Nor, as we have seen, did Wilson limit his interventions to our hemisphere. His reaction to the Russian Revolution solidified the alignment of the United States with Europe’s colonial powers. His was the first administration to be obsessed with the specter of communism, abroad and at home. Wilson was blunt about it.

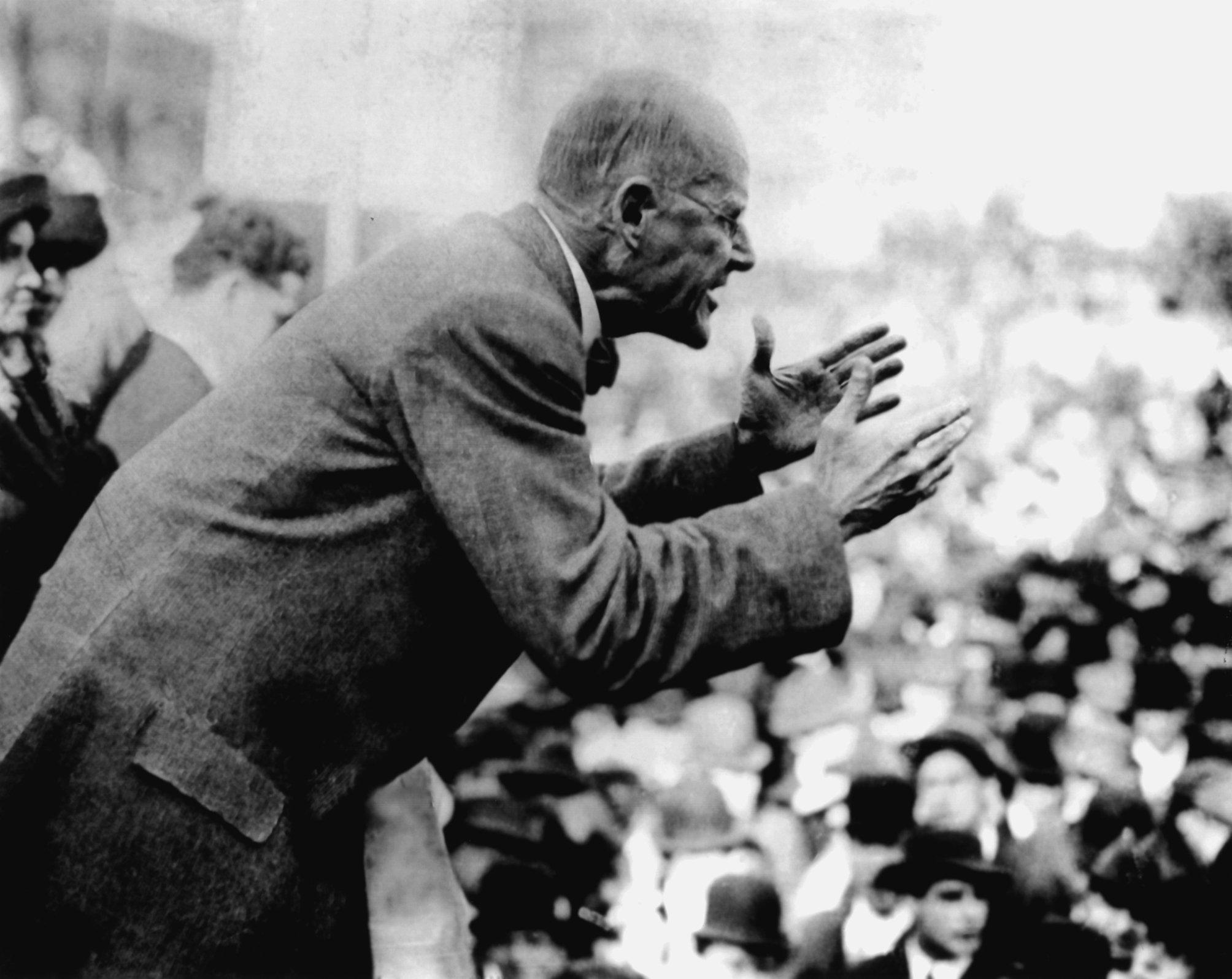

In Billings, Montana, stumping the West to seek support for the League of Nations, he warned, “There are apostles of Lenin in our own midst. I cannot imagine what it means to be an apostle of Lenin. It means to be apostle of the night, of chaos, of disorder.” Even after the White Russian alternative collapsed, Wilson refused to extend diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union. He participated in barring Russia from the peace negotiations after World War I and helped oust Béla Kun, the communist leader who had risen to power in Hungary.

Ho Chi Minh, standing, as member of French Socialist Party at Versailles Peace Conference, 1919. Source: Library of Congress

Wilson’s sentiment for self-determination and democracy never had a chance against his three bedrock “ism”s: colonialism, racism, and anticommunism. A young Ho Chi Minh appealed to Woodrow Wilson at Versailles for self-determination for Vietnam, but Ho had all three strikes against him. Wilson refused to listen, and France retained control of Indochina. It seems that Wilson regarded self-determination as all right for, say, Belgium, but not for the likes of Latin America or Southeast Asia.

At home, Wilson’s racial policies disgraced the office he held. His Republican predecessors had routinely appointed Blacks to important offices, including those of port collector for New Orleans and the District of Columbia and register of the treasury. Presidents sometimes appointed African Americans as postmasters, particularly in southern towns with large Black populations. African Americans took part in the Republican Party’s national conventions and enjoyed some access to the White House. Woodrow Wilson, for whom many African Americans voted in 1912, changed all that.

A Southerner, Wilson had been president of Princeton, the only major northern university that flatly refused to admit Black people. He was an outspoken white supremacist — his wife was even worse — and told “darky” stories in cabinet meetings. His administration submitted an extensive legislative program intended to curtail the civil rights of African Americans, but Congress would not pass it. Unfazed, Wilson used his power as chief executive to segregate the federal government. He appointed Southern whites to offices traditionally reserved for Blacks.

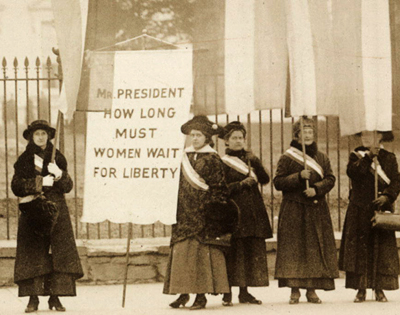

His administration used the excuse of anticommunism to surveil and undermine Black newspapers, organizations, and union leaders. He segregated the navy, which had not previously been segregated, relegating African Americans to kitchen and boiler work. Wilson personally vetoed a clause on racial equality in the Covenant of the League of Nations. The one occasion on which Wilson met with African American leaders in the White House ended in a fiasco as the president virtually threw the visitors out of his office.

Wilson’s legacy was extensive: he effectively closed the Democratic Party to African Americans for another two decades, and parts of the federal government remained segregated into the 1950s and beyond. In 1916 the Colored Advisory Committee of the Republican National Committee issued a statement on Wilson that, though partisan, was accurate: “No sooner had the Democratic Administration come into power than Mr. Wilson and his advisors entered upon a policy to eliminate all colored citizens from representation in the Federal Government.”

Of all the history textbooks I reviewed, eight never even mention this “black mark” on Wilson’s presidency. Only four accurately describe Wilson’s racial policies. Land of Promise, back in 1983, did the best job:

Of all the history textbooks I reviewed, eight never even mention this “black mark” on Wilson’s presidency. Only four accurately describe Wilson’s racial policies. Land of Promise, back in 1983, did the best job:

Woodrow Wilson’s administration was openly hostile to black people. Wilson was an outspoken white supremacist who believed that black people were inferior. During his campaign for the presidency, Wilson promised to press for civil rights. But once in office he forgot his promises. Instead, Wilson ordered that white and black workers in federal government jobs be segregated from one another. This was the first time such segregation had existed since Reconstruction! When black federal employees in Southern cities protested the order, Wilson had the protesters fired. In November 1914, a black delegation asked the President to reverse his policies. Wilson was rude and hostile and refused their demands.

Most of the textbooks that do treat Wilson’s racism give it only a sentence or two. Some take pains to separate Wilson from the practice: “Wilson allowed his Cabinet officers to extend the Jim Crow practice of separating the races in federal offices” is the entire treatment in Pathways to the Present.

Omitting or absolving Wilson’s racism goes beyond concealing a character blemish. It is overtly racist. No Black person could ever consider Woodrow Wilson a hero. Textbooks that present him as a hero are written from a white perspective. The cover-up denies all students the chance to learn something important about the interrelationship between the leader and the led. White Americans engaged in a new burst of racial violence during and immediately after Wilson’s presidency. The tone set by the administration was one cause. Another was the release of America’s first epic motion picture.

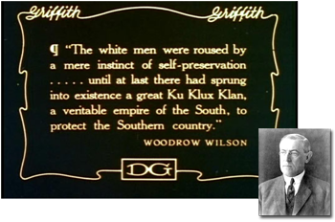

The filmmaker D. W. Griffith quoted Wilson’s two-volume history of the United States, now notorious for its racist view of Reconstruction, in his infamous masterpiece The Clansman, a paean to the Ku Klux Klan for its role in putting down “Black-dominated” Republican state governments during Reconstruction. Griffith based the movie on a book by Wilson’s former classmate, Thomas Dixon, whose obsession with race was “unrivaled until Mein Kampf,” according to historian Wyn Wade.

At a private White House showing, Wilson saw the movie, now retitled Birth of a Nation, and returned Griffith’s compliment: “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so true.” Griffith would go on to use this quotation in successfully defending his film against NAACP charges that it was racially inflammatory.

At a private White House showing, Wilson saw the movie, now retitled Birth of a Nation, and returned Griffith’s compliment: “It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so true.” Griffith would go on to use this quotation in successfully defending his film against NAACP charges that it was racially inflammatory.

This landmark of American cinema was not only the best technical production of its time but also probably the most racist major movie of all time. Dixon intended “to revolutionize northern sentiment by a presentation of history that would transform every man in my audience into a good Democrat! . . . And make no mistake about it — we are doing just that.” Dixon did not overstate by much.

Spurred by Birth of a Nation, William Simmons of Georgia reestablished the Ku Klux Klan. The racism seeping down from the White House encouraged this Klan, distinguishing it from its Reconstruction predecessor, which President Grant had succeeded in virtually eliminating in one state (South Carolina) and discouraging nationally for a time. The new KKK quickly became a national phenomenon. It grew to dominate the Democratic Party in many Southern states, as well as in Indiana, Oklahoma, and Oregon.

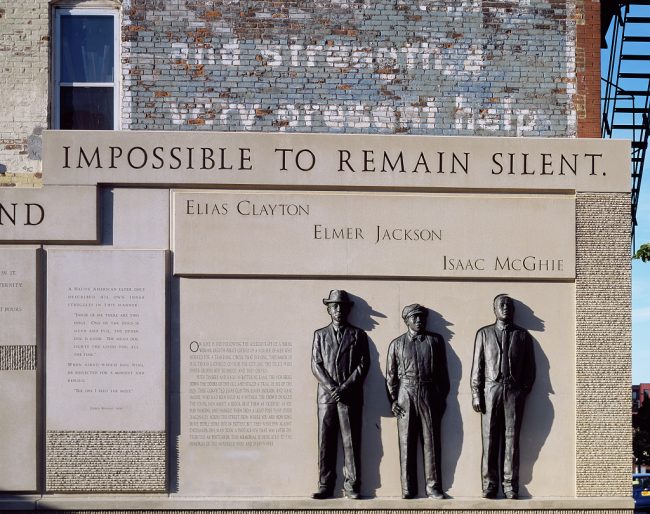

Klan spectacles in the 1920s in towns from Montpelier, Vermont, to West Frankfort, Illinois, to Medford, Oregon, were the largest public gatherings in their history, before or since. During Wilson’s second term, a wave of anti-Black race riots swept the country. Whites lynched Blacks as far north as Duluth.

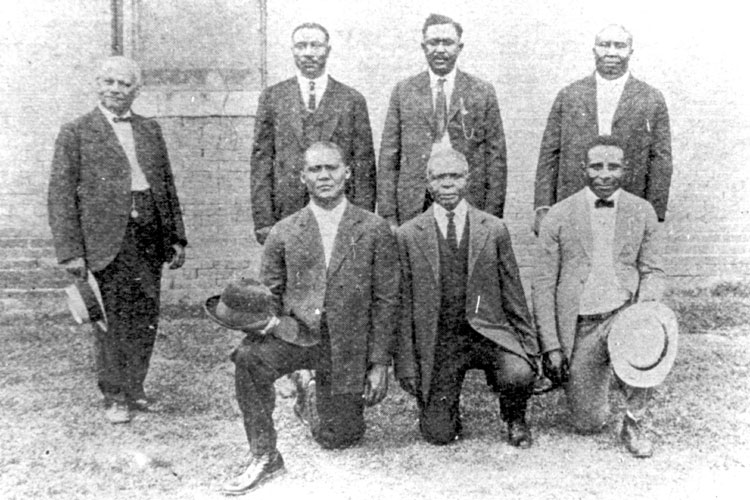

Three Black circus workers were attacked and lynched by a mob in Duluth, Minnesota in June of 1920. Source: Library of Congress.

Americans need to learn from the Wilson era, that there is a connection between racist presidential leadership and like-minded public response. To accomplish such education, however, textbooks would have to make plain the relationship between cause and effect, between hero and followers. Instead, they reflexively ascribe noble intentions to the hero and invoke “the people” to excuse questionable actions and policies. According to Triumph of the American Nation: “As President, Wilson seemed to agree with most white Americans that segregation was in the best interests of Black as well as white Americans.”

Wilson was not only anti-Black; he was also far and away our most nativist president, repeatedly questioning the loyalty of those he called “hyphenated Americans.” “Any man who carries a hyphen about with him,” said Wilson, “carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready.” The American people responded to Wilson’s lead with a wave of repression of white ethnic groups; again, most textbooks blame the people, not Wilson. The American Tradition admits that “President Wilson set up” the Creel Committee on Public Information, which saturated the United States with propaganda linking Germans to barbarism. But Tradition hastens to shield Wilson from the ensuing domestic fallout: “Although President Wilson had been careful in his war message to state that most Americans of German descent were ‘true and loyal citizens,’ the anti-German propaganda often caused them suffering.”

This excerpt is reprinted by permission of the author. There is more about Woodrow Wilson in Lies My Teacher Told Me and a number of entries in James Loewen’s Lies Across America:What Our Historic Sites Get Wrong.

Below are additional resources related to Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, including the horrific events of Red Summer of 1919 and the Sedition Act.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn