the day I was born is a collection of oral history interviews and photographs from the Arkansas Delta (primarily in Earle), by photographer, writer, and filmmaker Eugene Richards.

the day I was born is a collection of oral history interviews and photographs from the Arkansas Delta (primarily in Earle), by photographer, writer, and filmmaker Eugene Richards.

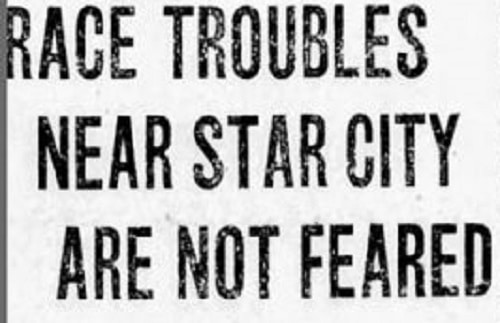

Earle, Arkansas, is one of countless towns with a history of Civil Rights Movement activism and violent white resistance that do not make the history textbooks.

The resistance in Earle turned into a riot on September 10 and 11, 1970, when “a group of whites armed with guns and clubs attacked a group of unarmed African Americans who were marching to the city hall in Earle to protest segregated conditions in the town’s school system. Five African Americans were wounded, including two women who were shot.” The protestors were also demanding that the polluted town dump be moved from the Black neighborhood. (These events are described in detail in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas in two entries: Earle Race Riot and William Ezra Greer.)

Richards had been in the Arkansas Delta as a VISTA volunteer. Then he helped found a social service organization and newspaper, for which he was a reporter and photographer. In early 2019, Richards returned to the region to examine change. While there, he went to Earle “with the single purpose of revisiting a place I’d reported on when a young journalist 50 years earlier.”

People he met were eager to talk about their lives. Among these conversations, were stories about the history of protest and social change in the region, systemic racism, poverty, Black history, abuse of women, and the struggle to be what you want to be. Recognizing the power of these deeply personal stories, Richards recorded and collected them in the 160-pages of the day I was born, published by Many Voices Press in 2020, with full color photographs.

Thanks to a generous donor, hundreds of copies of the $60 book were made available free to teachers for their lessons on Arkansas history, U.S. history, and/or on approaches to oral history collection. Now, it can be purchased from the author’s website.

To learn about the stories in the book, read the following essay by Robert Dannin, an independent scholar in linguistics and anthropology. Dannin collaborated with Richards when they both worked at Magnum Photos, was a student of Howard Zinn’s at Boston University, and contributes to the Zinn Education Project.

The Many Voices of the Arkansas Delta

By Robert Dannin

The march, it’s mostly forgotten. Earle is nothing but a little out-of-the-way place that most people haven’t heard anything about. We never really did get much news coverage. We’re too far from Little Rock. And in Memphis, unless there’s a murder, they hardly holler, didn’t bother about coming. (pp. 148 – 149)

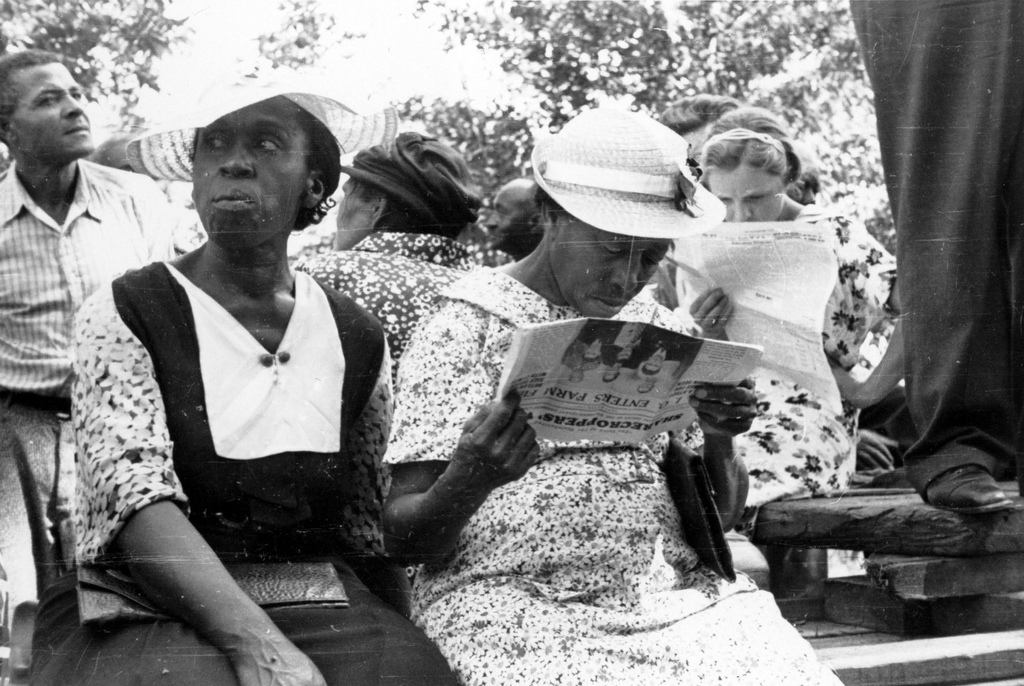

So concludes Jackie Greer in recounting the history of a 1970 civil rights march in the delta town of Earle, Arkansas. Her friend, Jessie Mae Maples, was shot in the back and despite serious damage to her vital organs kept on walking. “I was shot bad, but never did fall down. I never did lose consciousness, till they put me in the hospital and had to do surgery. I lost my kidney, my spleen, part of my pancreas” (p. 127).

Jessie Mae survived to testify about the reign of terror on peaceful protesters that September night. More astounding perhaps was the unexpected apology she received years later from a local town official, a white man. Was it a confession? Perhaps. Yet no one was ever charged or arrested for this brutal attack. After nearly a half-century Maples still has her bloodstained clothes and vivid memories of the struggle for change in the little town of Earle.

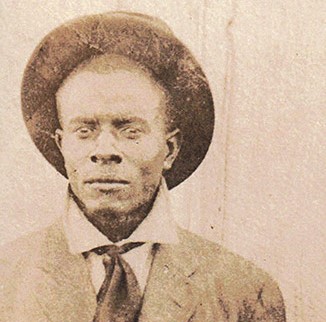

In the tradition of James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a widely heralded chronicle of the Great Depression, Eugene Richards’ the day I was born (Brooklyn: Many Voices Press, 2020) explodes the myth — once again — that history is conducted by celebrities on a television screen before a national audience. In words and pictures, the day I was born depicts the enduring, conflict-plagued legacy of African Americans’ steadfast resistance to slavery and their unswerving demand for equality. From the first page onward, it resuscitates the intimate personal narrative as the cry of freedom and testament to hope for the generations silenced not only by institutional racism but also by a mass media deaf to their voices, blind to their tears, indifferent to their fate.

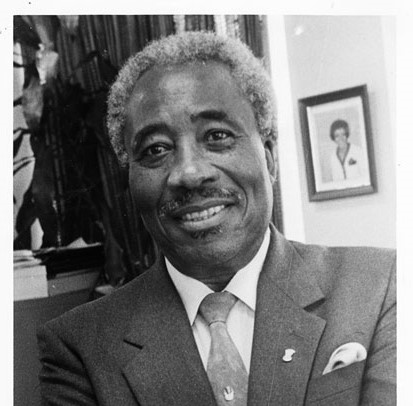

The Black citizens of Earle tell horrific stories. Change has come at a snail’s pace mostly to the once segregated town where racial, gender, and class prejudice still simmer beneath the surface. Joseph Perry Jr. explains the broken legacy of Civil War and Reconstruction, chronic unemployment, and the twisted psychology of status based on skin tone (pp. 11-14). Lovell Davis takes the reader from his childhood of deep poverty — “. . . never owned a toy … ragged and dirty [and hungry] . . .” — through a tyrannical criminal justice system (pp. 81-94).

No details are spared in recounting the hours of hard labor spent by children chopping cotton, mothers banding together to feed their families, students forced into inferior schools that were integrated in name only, and the grim realities of migrant labor. Longstanding taboos fall by the wayside in Timothy Way’s narrative about growing up gay amidst the community’s latent homophobia. Similarly, Jackie Greer and Lovell Davis pull no punches in describing segmented, reactionary church networks. Davis declares (p. 137):

What you had right here in Earle was 37 churches, and every one of them was separated. Every church, every pastor, want his pot. They won’t help put a grocery store in here. They won’t put a clothes store in here. They won’t put a service station in here. But we can bear witness in their church.

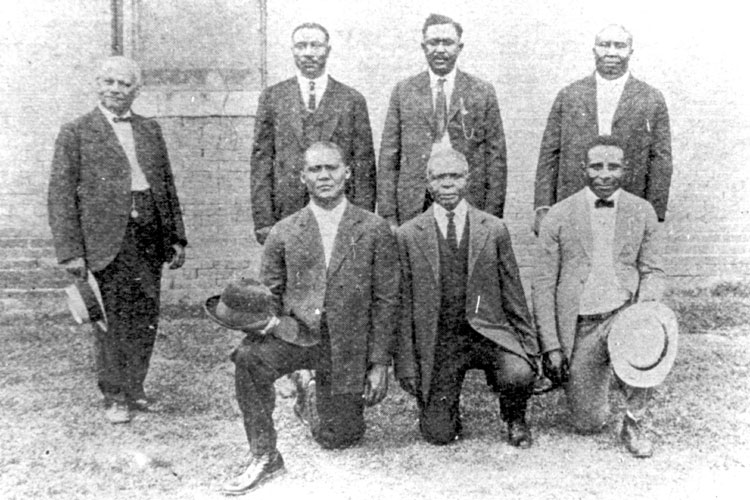

Resistance was diverse and creative. Women and children led the fight against Jim Crow with boycotts of local businesses, high school walkouts, and ballot box activism. Undeterred by police violence they challenged environmental racism years before the first Earth Day. Businessman Stacy Abram decided to combat the symbolic violence of the region’s ubiquitous Confederate monuments by hiring the talented artist Timothy Way to memorialize African American heroes in a series of monochrome portraits on the exterior of his appliance store. The fearless Rev. Ezra Greer arrived from Chicago to start the Soul Institute, an alternative school for Black students, while Lovell Davis rehabilitated himself through vocational training and higher education.

The book conveys important lessons: Change happens, sometimes rapidly as when the town dump was closed following the 1970 civil rights march, but more often social transformation is slow, cumulative, and arduous. Sadly, positive change is also reversible, meaning that newly acquired rights must be defended from one generation to the next. That can only happen with education of the kind provided by dedicated teachers armed with good materials. In this instance, Richards has deftly organized the book’s contents to bring us from the near historical past of the civil rights era into contemporary issues of intersectionality and wholesale marginalization marked by the intensified assault on human rights and the obscene national wealth gap. Arkansas is home to Walmart and its owners, America’s wealthiest family, who could improve life for everyone in the state by spending their pocket change only. Yet the state’s economic collapse brooks few distinctions. Poor white and Black people are increasingly besieged together on the precipice of bare existence. Timothy Way, for example, now shares Sandra Gray’s meager home where they care for a destitute white cancer patient.

These testimonies and others blaze with passion. They strike the reader like heat from an open furnace. Eugene Richards’ images punctuate the narratives with revealing portraits, landscapes, and close-up details of Timothy Way’s murals. He alternates voices and pictures to establish a rhythm internal to the book — a deliberate, remarkably successful experiment to channel between Earle’s personages and a wide audience, immersing them in this “little out-of-the-way place.”

the day I was born is a documentary masterwork, as cinematic and intense as any film or book ever to feature eyewitness accounts of contemporary life in the rural South. It will serve students and teachers as a template for recording their community’s social history through interviews and photographs. Because the personal narratives are so compelling and seamlessly woven together with pictures, the book makes it look like an easy exercise. Hardly the case though when considering the levels of intimacy and sincere contact required to probe the deepest memories of a bitter past whose truth is seldom if ever reflected in textbooks.

As a student at Boston University in 1970, I learned people’s history from the master. “Got a tape recorder, a car?” Professor Howard Zinn asked one day. “. . . OK, good.” He reached around his desk and handed me a note with a name, address and telephone number. “This man was treated unfairly and forced from his job. He’s got a story to tell. It’s important to get all of it,” he advised, flashing his characteristic glint. It was an invitation to undertake a serious assignment for the first time in my life.

Later that week I met Charles Ramsey at his house in Roxbury, Massachusetts. He had immigrated from Jamaica expecting to work hard and build a life to match his youthful dreams of equality and freedom. Yet the racism he experienced working as a dispatcher for a major trucking company disappointed and angered him. Behind his pain and seething indignation Ramsey was a humble, gentle man. Anticipating our interview, he had prepared a 20-page handwritten autobiography. It contained a poem about his boyhood trek to a local mountaintop where he envisioned a future of justice and equality. I don’t think he expected anything from me beyond the occasion to tell his story. I wasn’t a lawyer, he never intended to sue. But that was enough for him and for me; it was a powerful encounter of the kind that structures one’s values forever. Imagine the educational moment for an 18 year-old middle class kid. Zinn knew that such opportunities don’t arise from reading a few books or debating abstract issues in a classroom.

In 1969, Eugene Richards traveled to the Arkansas Delta for the first time as a VISTA volunteer. In 1970, he helped create RESPECT, Inc. a social service organization that published Many Voices, a newspaper for people living in the Arkansas Delta. the day I was born (2020) is his third publication documenting their lives, preceded by Few Comforts or Surprises (1973) and Red Ball of a Sun Slipping Down (2014). A lifetime of honing his craft went into producing this compressed oral-visual history of life in Earle from the Civil Rights Era to the present.

Read more by Dannin on the day I was born in Photocritic International (April, 2021) “The Many Voices of the Arkansas Delta” Part 1 and Part 2

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn