While most people know that students were killed at Kent State in 1970, very few know about the murder of students at Jackson State and even less about South Carolina State College in Orangeburg. In Orangeburg, two years before the Kent State murders, 28 students were injured and three were killed — most shot in the back by the state police while involved in a peaceful protest. One of the by-standers, Cleveland Sellers, was arrested for inciting a riot and sentenced to a year of in prison. Now president of Voorhees College, he was the only person to do time. Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968 is an excellent documentary which brings to light this untold story of the Civil Rights Movement including candid interviews with many of those involved in the event: students, journalists, officers on the scene, and the then-Governor. The film also provides students with a good understanding of the concept of Black Power in the context of the Civil Rights Movement.

Description of the Orangeburg Massacre

In 1968, Orangeburg was a typical Southern town still clinging to its Jim Crow traditions. Although home to two black colleges and a majority black population, economic and political power remained exclusively in the hands of whites. Growing black resentment and white fear provided the kindling; the spark came when a black Vietnam War veteran was denied access to a nearby bowling alley, one of the last segregated facilities in town. Three hundred protestors from South Carolina State College and Claflin University converged on the alley in a non-violent demonstration. A melee with the police ensued during which police beat two female students; the incensed students then smashed the windows of white-owned businesses along the route back to campus. The Governor sent in the state police and National Guard.

The three young men who were murdered: Henry Smith and Samuel Hammond, both SCSU students, and Delano Middleton, a local student at Wilkinson High School.

By the late evening of February 8th, army tanks and over 100 heavily armed law enforcement officers had cordoned off the campus; 450 more had been stationed downtown. About 200 students milled around a bonfire on S.C. State’s campus; a fire truck with armed escort was sent in. Without warning the crackle of shotgun fire shattered the cold night air. It lasted less than ten seconds. When it was over, twenty-eight students lay on State’s campus with multiple buckshot wounds; three others had been killed. Almost all were shot in the back or side. Students and police vividly describe what they experienced that night.

Journalists remember that the Governor and law enforcement officials on the scene claimed police had fired in self-defense. The Associated Press’ initial account, carried in newspapers the morning after the shooting, misreported what happened as “an exchange of gunfire.” The source, an AP photographer on the scene, subsequently revealed that he heard no gunfire from the campus.

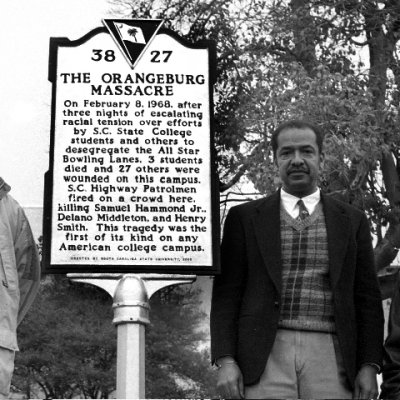

Cleveland Sellers stands beside the historic marker on the S.C. State University campus at the 2000 Orangeburg memorial. Photo by Cecil Williams.

In Orangeburg, police fingered Cleveland Sellers as the inevitable “outside agitator” who, they claimed, had incited the students. Twenty-three years old, he had returned home, leaving his position as Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) program director, to organize black consciousness groups on South Carolina campuses. Sellers had already attracted the attention of law enforcement officials as a friend of SNCC head Stokely Carmichael, who had frightened many Americans with his call for “Black Power.” Carmichael’s ideas articulated the Movement’s shift from a focus on integration to one of gaining political and economic power within the black community. South Carolina officials therefore saw Sellers as a direct challenge to their power. Wounded in the Massacre, Sellers was arrested at the hospital and charged with “inciting to riot.” Though students made clear he was only minimally involved with their demonstrations, Sellers was tried and sentenced to one year of hard labor. He was finally pardoned 23 years after the incident. The U.S. Justice Department charged the nine police officers who admitted shooting that night with abuse of power. However, neither of two South Carolina juries would uphold the charges.

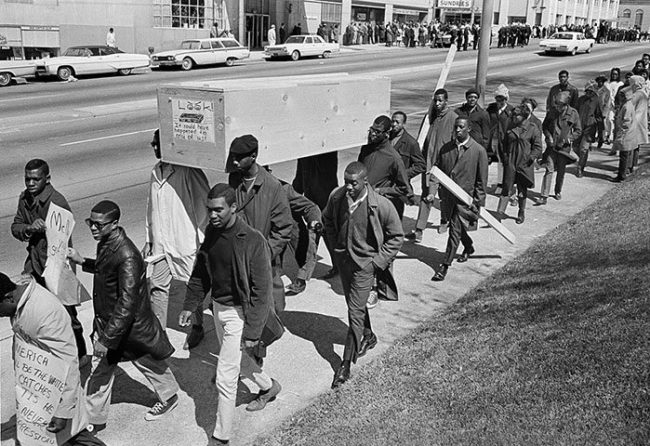

Demonstrators protest the shootings.

The Orangeburg Massacre has been excluded from most histories of the Civil Rights Movement. But forty years later, some remember the tragedy as if it happened only yesterday. The film interviews the most important participants on both sides of the tragedy, some of whom speak for the first time about the Massacre. The survivors are still visibly traumatized by that night, while the Governor and one of the accused policemen remain convinced they had no other choice. Two prominent Southern white journalists, Jack Bass and Jack Nelson, authors of The Orangeburg Massacre and historical consultants to the film, discuss their revealing, independent investigation. At an historic conference about South Carolina’s Civil Rights Movement, white officials try to evade discussion of the Massacre, arguing that an investigation isn’t warranted because it is time to move forward.’ However, African Americans insist that true reconciliation cannot begin without an investigation and report that finally sheds light on the many unanswered questions. Cleveland Sellers, now president of Voorhees, a historically black college in South Carolina, and his son, Bakari, at 21 the youngest state legislator in South Carolina history, call on us to remember those slain in Orangeburg with the other Civil Rights martyrs. With a resonance that carries us far beyond the tragedy itself, the film is a powerful antidote to historical amnesia. [Description from California Newsreel.]

Watch

Reviews

“The truth-telling power of history is made manifest in this profoundly moving and healing documentary.” —Darlene Clark Hine, Michigan State University

“This documentary should be shown in every schoolroom in America. We might then create a new generation of activists, emulating the heroic young people of that time, moving this country towards new levels of equality and justice.” —Howard Zinn

“This masterful film tells a story previously known by too few. Among its many lessons is the truth of the phrase no justice, no peace.’” —Julian Bond, NAACP Board Chairman

Distributed by California Newsreel.

Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968 is a co-production of Northern Light Productions, the Independent Television Service (ITVS) and the National Black Programming Consortium, with funds provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Sally Jo Fifer Executive Producer for ITVS.

- The Orangeburg Massacre by Jack Bass and Jack Nelson

- A Brother Lost To The Civil Rights Struggle. A Storycorps interview with Samuel Hammond Jr.’s sisters.

- 40 Years Ago: Police Kill Two Students at Jackson State in Mississippi, Ten Days After Kent State Killings. Interview with witness Gene Young on Democracy Now!

- 1968, Forty Years Later: A Look Back at the Orangeburg Massacre When SC Police Opened Fire on Black Students Protesting Segregation. Interview with Cleveland Sellers on Democracy Now!

I am 68 years old never heard of this,bad when people of law shoot you in back.

zinn history educates me more than honors history classes i took at U mich

This is the year I turned 18 and was enlisted in the navy I never heard of this event in history and this was the time of George Wallace running for president

This is why, we do not TRUST the Government or POLICE. What has changed? Laws on the books does not make them act accordingly. It’s 2015 and this is not mentioned in our HISTORY BOOKS. It’s truly amazing how THE POLICE & GOVERNMENT has gotten away with MURDERING our Talented and Beautiful Children for many years. My heart is so heavy.