Demonstration to protest the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. Source: Reuters/Lucas Jackson

Police violence against Black people is a fixture of students’ lives in the 21st century. It is a brutal reality that my students cannot always remember which unarmed Black victim they’re thinking of.

I recall a discussion at the beginning of the 2019–20 school year in which one student remarked, “I mean, what about the case of Botham Jean? That dude was just standing in his grandma’s backyard with his phone.”

Actually, that was Stephon Clark.

Botham Jean was killed while eating ice cream in his own apartment by an off-duty cop who said she thought she was entering her own apartment. My students’ confusion is both understandable and horrifying. But the shamefully long list of Black people murdered by police in the last decade can also lead to a major misconception: that we’re witnessing something altogether new.

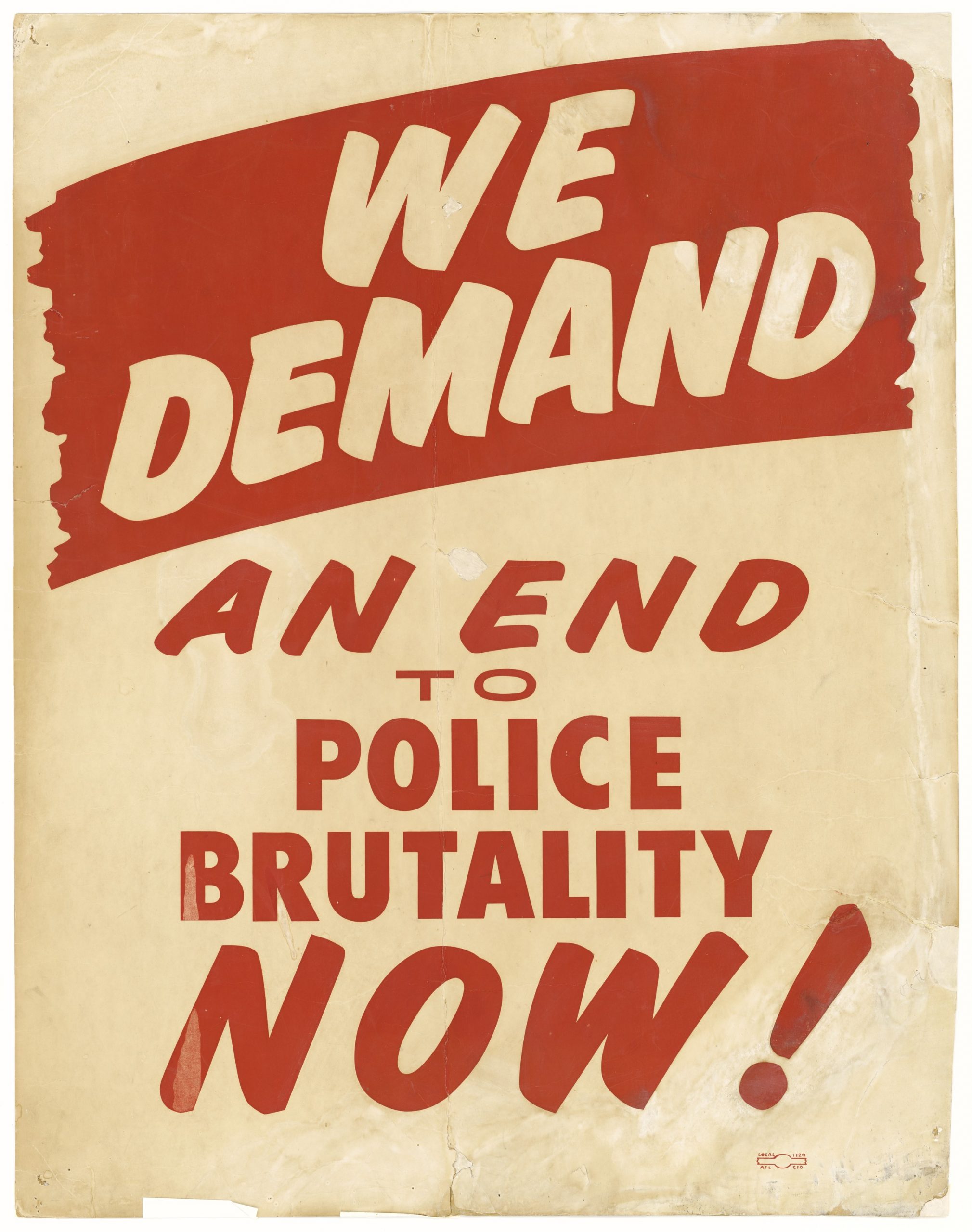

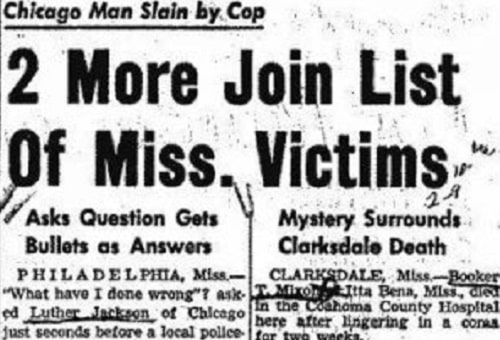

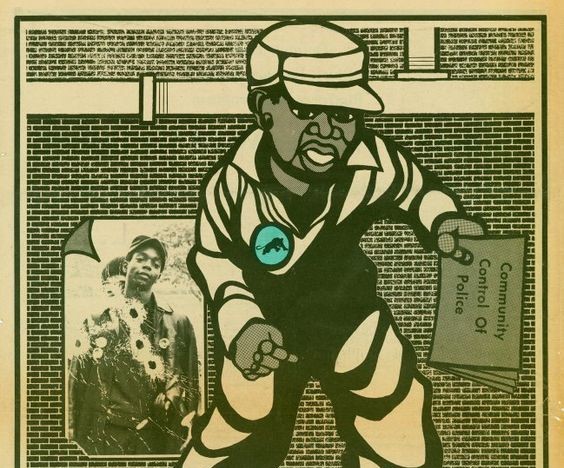

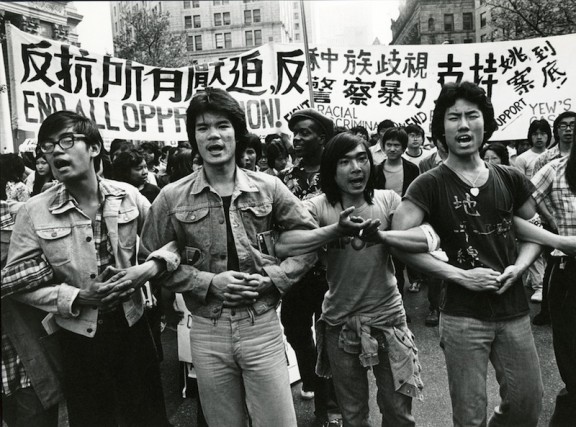

The oppressive and violent relationship between police and Black communities is not new. Indeed, the history of Black people in the United States is scarred by perennial state violence. (While the focus here is on African Americans, the U.S. state has also wielded its genocidal and oppressive machinery against many others: Native Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx people, immigrants, and, of course, against countless peoples in the path of its war-making across the globe.)

I created this lesson to kick off a unit that asks “What is the function of the police? And are they serving that function?” Ultimately, the unit aims to help students articulate their own understanding of what constitutes security and safety and learn enough about the history of the police in the United States to grapple with the question of abolition versus reform. But first, I wanted students to grasp the historical magnitude of the problem, to understand that Black distrust of police is not new nor are the police practices that give rise to it.

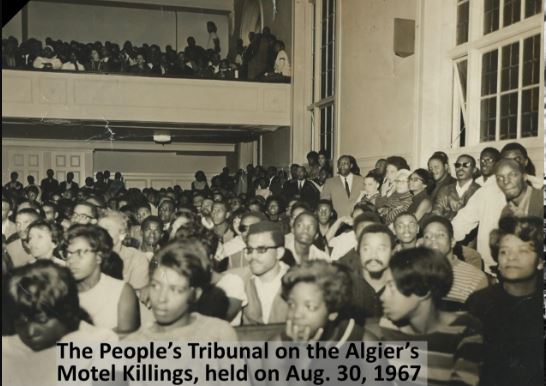

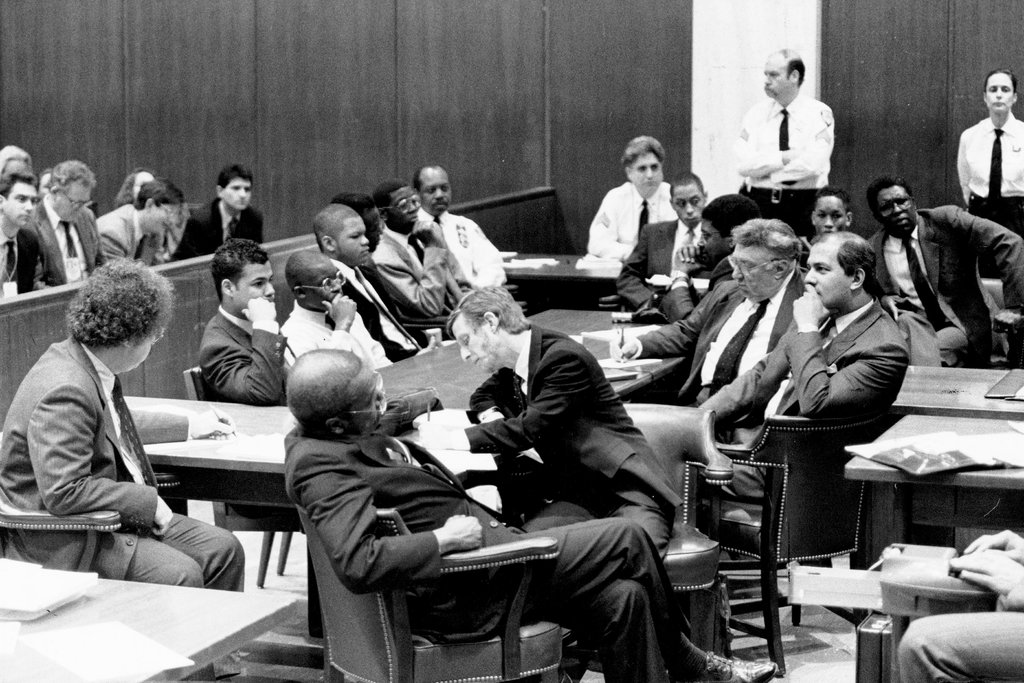

In this lesson, students examine excerpts from three reports, written in 1922, 1968, and 2015, about three major episodes of racial violence, the Chicago Riot of 1919, the “long, hot summer” of 1967, and the Ferguson Uprising of 2014.

Analyzing these documents does not enable students to answer the questions “What is the function of the police?” and “Do the police create conditions of safety and security?” Rather, this lesson clarifies for students the long trajectory of police violence and misconduct in Black communities, critical information for evaluating the most common proposals offered by policymakers. The older and more entrenched the problem, the more likely that quick fix reforms will fail. For example, in any inquiry into debates around police reform, students will surely encounter the notion that one solution to racist police violence is to hire more Black and People of Color cops. With these reports in hand, students may well wonder, “If the percentage of Black police officers has steadily risen over the last 100 years, but these three reports identify the same problems, then how effective are diversity initiatives in police departments?”

The goal of the lesson is simple but ambitious: I want my students to recognize the continuities between past and present, better equipping them, I hope, to dream up new solutions to old — and very dangerous — problems.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn