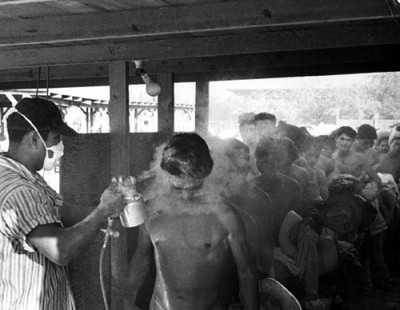

Mexicans wait to be bathed and deloused at the Santa Fe Bridge quarantine plant, 1917. Source: National Archives

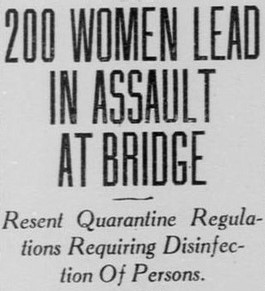

On Jan. 28, 1917, 17-year-old Carmelita Torres, who crossed the border daily from Juarez to clean houses in El Paso, refused to take a toxic disinfectant bath. Press accounts estimated that, by noon, she was joined by several thousand demonstrators at the border bridge. The protest became known as the “Bath Riots.”

By David Dorado Romo

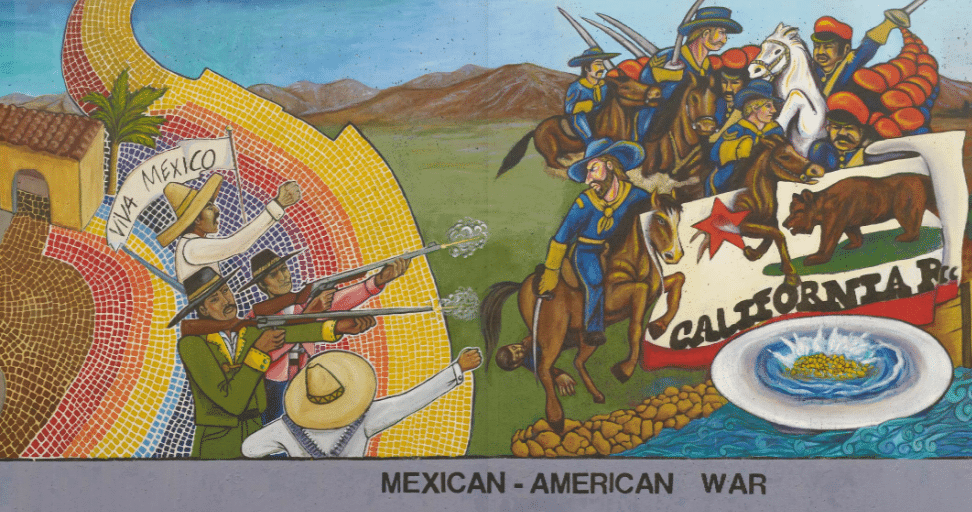

Mexican border crossers were not considered illegal in the United States until 1917, when a new law imposed formidable barriers to entry: a literacy test, a head tax and a prohibition against contract labor. Mexican nationals for the first time needed a passport to enter the United States. That’s also the year that the U.S. entered World War I.

The war stirred deep feelings of paranoia and anti-foreigner patriotism in this country. Americans were afraid that Germans would launch bombing raids from Mexico. As a protest against Germany, Americans changed the name of frankfurters to hot dogs and sauerkraut to “liberty cabbage.” And to protect the country from the threat of typhus, U.S. Customs agents began the mandatory delousing of Mexican border crossers at the El Paso-Juarez international bridge; 127,000 people were subjected to this procedure in 1917 alone.

All immigrants from the interior of Mexico, and those whom U.S. Customs officials deemed “second-class” residents of Juarez, were required to strip completely, turn in their clothes to be sterilized in a steam dryer and fumigated with hydrocyanic acid, and stand naked before a Customs inspector who would check his or her “hairy parts” — scalp, armpits, chest, genital area — for lice. Those found to have lice would be required to shave their heads and body hair with clippers and bathe with kerosene and vinegar.

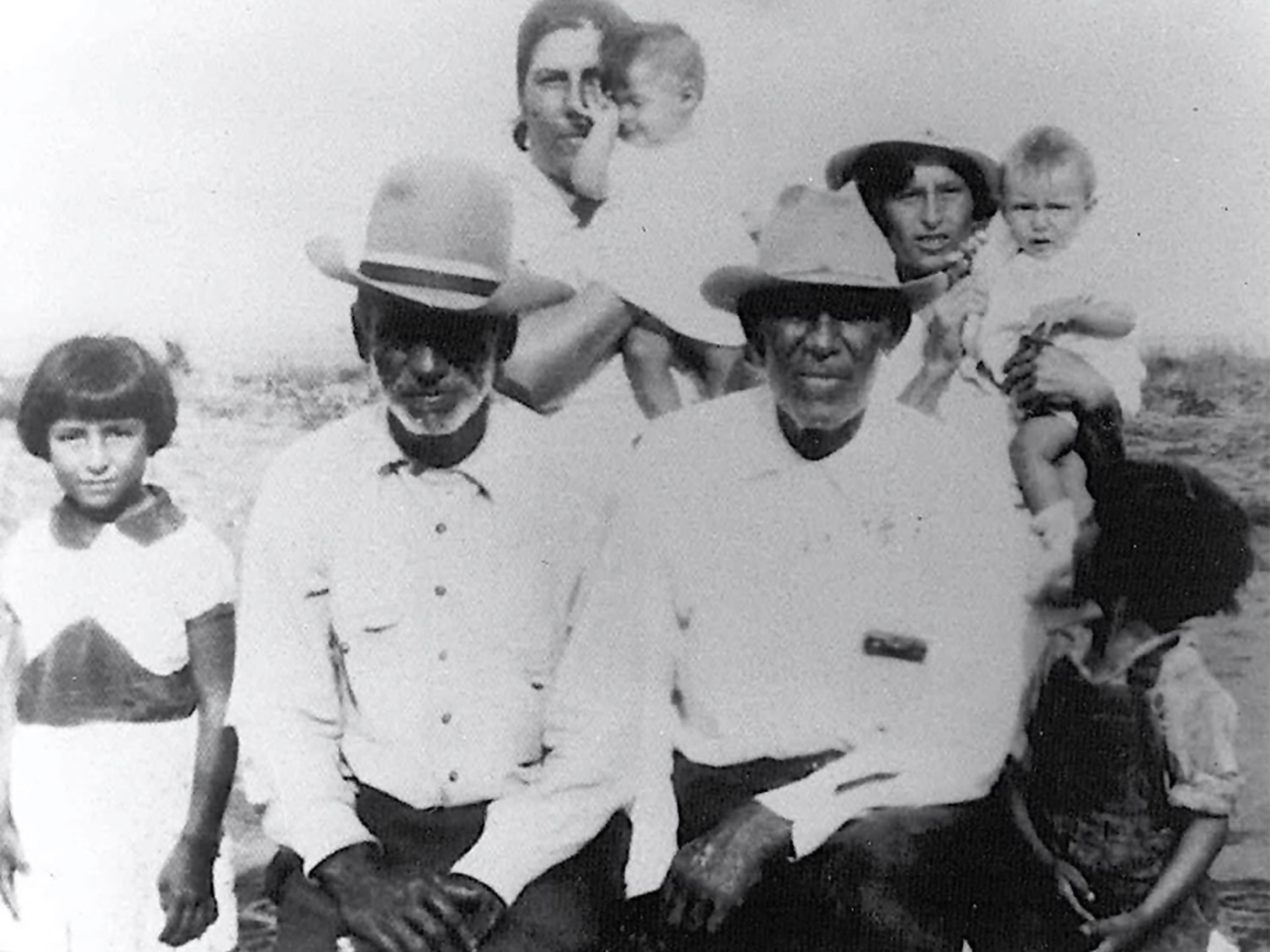

My great-aunt, Adela Dorado, would tell our family about the humiliation of having to go through the delousing every eight days just to clean American homes in El Paso. She recalled how on one occasion the U.S. Customs officials put her clothes and shoes through the steam dryer and her shoes melted.

Contract Mexican laborers being fumigated with the pesticide DDT in Hidalgo, Texas, in 1956. Source: National Museum of American History

Beyond the indignity of the process, there was a real danger of being burned in a fire. That happened in 1916 in the El Paso city jail, when someone struck a match near a tub during the mayor’s disinfection campaign and 27 prisoners burned to death.

On Jan. 28, 1917, a 17-year-old Juarez maid named Carmelita Torres, who crossed the border daily to clean houses in El Paso, refused to take a bath and be disinfected. Press accounts estimated that, by noon, she was joined by “several thousand” demonstrators at the border bridge. The protest became known as the “Bath Riots.”

The local Anglo press did everything it could to sensationalize the typhus threat from Mexico, although one U.S. Public Health Service official stated that the typhus problem in El Paso was no worse than it was in most major cities in the United States. In 1917, there were 31 typhus cases in the United States and only three typhus-related fatalities in El Paso.

Yet the delousings went on for decades along the U.S.-Mexican border, long after the threat had passed of either a typhus epidemic or German bombers. Even up to the late ’50s, during the guest-worker bracero program, Mexican laborers were still being sprayed with DDT before being allowed into the United States. Why? Because the paranoia not only was about physical contamination, it also was about the cultural and genetic kind.

—Continue reading “Crossing the line” in the LA Times, based on Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez: 1893-1923.

The Dark History of “Gasoline Baths” at the Border

Watch the 15-minute Vox, “Missing Chapter” documentary below, produced by Ranjani Chakraborty.

The Bath Riots: Indignity Along the Mexican Border

As part of my research for this book at the National Archives in the Washington, D.C. area, I came upon some photographs taken in 1917 in El Paso. The pictures, which were part of the U.S. Public Health records, showed large steam dryers used to disinfect the clothes of border crossers at the Santa Fe Bridge.

I also unexpectedly uncovered other information at the National Archives that took my great-aunt’s personal recollections beyond family lore or microhistory. These records point to the connection between the U.S. Customs disinfection facilities in El Paso-Juárez in the 20s and the Desinfektionskammern (disinfection chambers) in Nazi Germany.

The documents show that beginning in the 1920s, U.S. officials at the Santa Fe Bridge deloused and sprayed the clothes of Mexicans crossing into the U.S. with Zyklon B. The fumigation was carried out in an area of the building that American officials called, ominously enough, “the gas chambers.” I discovered an article written in a German scientific journal written in 1938, which specifically praised the El Paso method of fumigating Mexican immigrants with Zyklon B. At the start of WWII, the Nazis adopted Zyklon B as a fumigation agent at German border crossings and concentration camps.

Later, when the Final Solution was put into effect, the Germans found more sinister uses for this extremely lethal pesticide. They used Zyklon B pellets in their own gas chambers not just to kill lice but to exterminate millions of human beings.

—Continue reading “The Bath Riots: Indignity Along the Mexican Border,” produced for NPR by John Burnett

Learn More

|

Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez: 1893-1923 by David Dorado Romo. 2005. The Mexican Revolution from a people’s perspective on both sides of the border. Published by Cinco Puntos Press. Howard Zinn wrote,

David Romo’s Ringside Seat to a Revolution is a fascinating glimpse into unknown scenes of the Mexican Revolution of 1911. He takes us into El Paso and Juárez — facing one another across the Rio Grande — in the years just before and just after the exciting events of the revolution itself. It is close up and personal history-through the eyes of an extraordinary cast of characters. It is ‘people’s history’ at its best. |

|

“Carmelita” is classroom-friendly ballad about the Bath Riots composed by Joe DeFilippo and performed by the R. J. Phillips Band, a group of Baltimore studio musicians. Listen for free on SoundCloud. |

Find related lessons, books, and articles below.

Another song about the bath riots

https://nobleinsect.bandcamp.com/track/bath-riot

My grandparents came from Mexico in 1920, crossing into Nogales, Arizona. I wonder if they had to undergo this procedure?