Letter to the Editor

Letter to the Editor

Route 1 Box 70

Hattiesburg, Mississippi

January 23, 1960

SCHOOL MIX

Editor, The American

The discussion of the problem of integration which faces our state at this time, prompts me to offer a statement, not in defense of my efforts to enroll at Mississippi Southern College, but as an explanation of our position on public school integration.

Mississippi Southern College is the only State supported four year college in this area and my situation at home makes it very difficult for me to leave home to continue my education. On this account I have been unable to attend school for nearly five years. By attending Mississippi Southern College my problem would be solved, as I could live at home and attend school.

From a general point-of-view I am keenly aware of the race problem entailed, as nothing has so constantly occupied my thoughts during the past three years. I know that there are those among us who feel that both races would be best benefited by a policy of private and public separation of the races, and that this segregation should be maintained no matter what the cost to ourselves and to future generations.

Unfortunately, perhaps I have not been able to convince myself, nor has anyone else been able to convince me that this is really the wisest course for Mississippi to follow at this critical juncture in our history.

Those who advocate the separation of the races theory generally say: To teach Negro and White students in the same schools would mean, in part, mixing of White and Negro blood to the extent of destroying both races; Negroes as a result of their economic and social history, have developed such low moral habits until it would be tragically degrading to White youngsters for them to associate with Negro youngsters; since White students are so much more advanced scholastically than Negro students it would be a grave injustice to Negro students to have them compete in the same class room, for since Negroes are so inferior in development to White students this would end even the little development which they are capable of making when left to themselves; if schools are racially integrated, Negro teachers would have to turn to some other income source here in Mississippi or leave the State completely for employment; and if schools maintained for Negro people are equal in facilities and teachers to those maintained for White people, then the schools are equal in total essence.

Although, I have tried never to underestimate the importance that many people attach to being of a certain racial group, I have not been able to discern a noticeable difference, other than color, between a good White man and a good Black or Yellow man.

I would be in favor of a commission of eminent social scientists to make a careful study of colleges and universities which have practiced total integration over a long period of time to determine whether or not the purity of any races involved has been greatly diluted, and if so, to what extent this dilution has actually impaired the effectiveness of those involved.

The study of such a commission would show, I believe, that the percentage of interracial courtships which led to anything as serious as marriage or reproduction would be so small as to be completely negligible. Should such a commission report a contrary result, however, then I would be among the first to about-face and join, actively, the segregationists among us.

The second major objection which segregationists advance against racial integration is the question of morality. No thinking person would pass lightly over this problem; for it is no secret that the percentage of Negroes who are accused of crime is higher than the Whites. I admit that we have had and still have, to a large extent, lower economic and moral standards than many of our White neighbors. However, we must realize that this condition is not a cause for segregation, but the effect of segregation and discrimination. The more segregation and discrimination we have in our community the more we shall continue to have ignorance and immorality and poverty.

To those who think that it would be an injustice to Negroes to have them compete with White students; the answer is found in the fact that our plan is to establish a system of education and not a temporary scheme to relieve ourselves of a problem which we are not willing to face. Certainly, there will be instances at first where Negro students are behind White students in development; though not because of any natural inferiority, but because the society in which we live has long failed to abide by its own contract to provide equal educational facilities for all of its children. There will be scattered instances where Negroes might fall behind White students, but shortly this problem would be, for the most part, eliminated.

Others maintain that integration is all right, but it would put an end to the employment of Negro teachers. Those who feel this way seem not to correctly appraise the transition. In the first place, it will take many years to drastically change the present patterns of our community; for years we shall continue to have areas predominantly White, and areas primarily Negro. The law will not have to require this arrangement; the pride which people have in their homes, churches, and schools will motivate this stability.

What seems to be the second major defect in their argument is the idea that the same prejudices which are leveled against Negroes before integration will remain after integration. This will not be the case. We are entering a period in which merit must rule the selection of teachers. There was a time when a person could get through college by hook or crook, and if he could do nothing else he would teach. This practice is rapidly becoming a thing of the past; in tomorrow’s world it will be unheard of. Thus, if a teacher has mastered his profession, and has made the proper adjustments, and is willing to dedicate himself to man’s highest calling, though he is yellow, black or white, there will be a place for him.

Finally, let me mention the argument for separate but equal facilities in public education, as being superior to a non-restricted system. This argument may seem more plausible if getting an education were an end in itself, and not a means to an end. The end product of an education is a greater and more useful participation in the art of living in a civilized society. If an education does not help make out of people more useful citizens to themselves and their community, then it has failed. Conversely, if the community fails to provide those whom it educates an opportunity to serve it to the fullest extent, then the community is guilty of self-impoverishment or self-destruction.

This is why I have not been able to understand what good an equalization program could serve, if no sincere plans are being made to equalize employment opportunities. If there are to be no jobs in government, science, or industry, the time and money spent in educating the child are in vain. The question seems, to be, what part will the educated Negro play in our society in future years? If we plan to continue our policy of employing all White on our hospital staffs, all White in government service, all White on engineering staffs, all White in anything which requires the least amount of brain-power, what will the thousands of Negroes do who will be graduating each year? On the other hand, if we decide to be realistic and fair about the whole thing, and employ people according to merit, would it not be much more sensible and certainly more economical to permit the lawyers, doctors and engineers who are to be working on the same staffs just after graduation, to go to the same schools where they could learn to respect and appreciate each other?

Questions of this kind have led me to request that I be permitted to enroll at Mississippi Southern College, without a court order to do so. I, too, am a solid believer in the ability, of the individual States to control their own affairs. I believe that if this State should lead out with only the smallest amount of integration, it would never have to worry about Federal intervention.

I have done all that is within my power to follow a reasonable course in this matter. I have wanted the State to see that our position has at least some validity. I have tried to make it clear that my love for the State of Mississippi and my hope for its peaceful prosperity is equal to any man’s alive. The thought of presenting this request before a Federal Court for consideration, with all the publicity and misrepresentation which that would bring about, makes my heart heavy. Yet, what other course can I take?

Respectfully submitted,

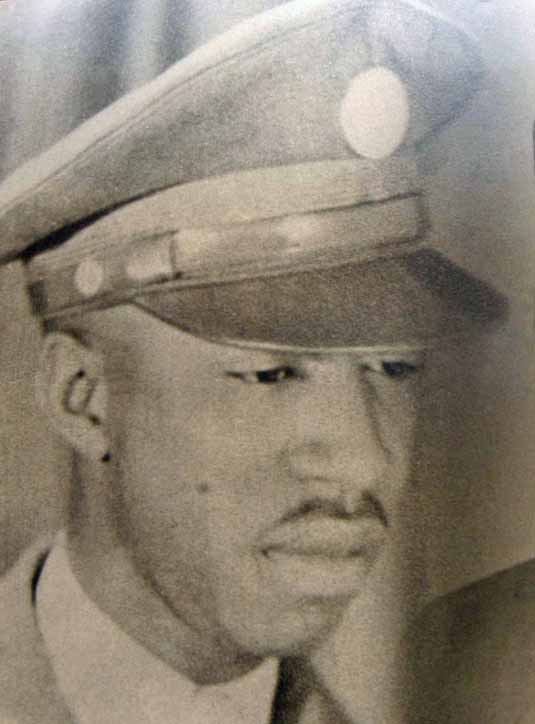

Clyde Kennard

Letter transcribed with original punctuation. Read about Clyde Kennard.

The letters were provided by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) Sovereignty Commission Collection.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn