By Dave Zirin

By Dave Zirin

Even in football, a sport whose DNA is constructed to produce obedience and deference to authority, people can be pushed only so far before they push back. At Grambling State, the players engaged in a players’ strike, what all media outlets are calling “a mutiny”, and refused to take the field on Saturday against Jackson State. It just lasted one game, but only because the administration and powers that be made a series of promises to get them back on the field.

They had little choice. The list of grievances at the school that the late Hall of Fame Coach Eddie Robinson called home is both long and startling. From unsanitary locker room conditions that have led to multiple cases of staph infection” as well as “mildew and mold on the ceiling, walls and floor,” to 750-mile overnight bus rides before games, to a weight room that appears to be an ugly accident waiting to happen, to having their popular coach, former Grambling quarterback Doug Williams summarily fired, this is a team of young people that has simply had enough. (Read their grievance letter in its entirety here.)

Some of the players’ frustration stems from the numerous cases of infighting by the adults in charge, but the root cause of the chaos can be found in the Louisiana Governor’s office of Bobby Jindal. Governor Jindal rejected federal stimulus funds in 2009, while also cutting 219 million dollars in state funds for higher education, $5 million of which would have gone to Grambling State. In 2012, Jindal cut another million that was due to go to Grambling State’s operating costs.

This has hammered the entire school, and the athletic department is no exception. At a school where players are self-rationing weight-lifting supplements to make sure everyone gets a fair share, every dollar matters. But as necessarily as it is to call out Governor Jindal, the Obama administration’s record on supporting historically black colleges and universities has also been, to be kind, brutal, with decreases in federal grant funding and changes in loan programs that have estimated to have cleaved $300 million from HBCU’s nationally.

Now a football school that as recently as 2011 won their conference title has not come within ten points of an opponent all season and the players are saying enough is enough.

The Grambling player’s strike has been covered very well, in my view, by all corners of the sports media, airing the grievances of the players and turning this into a national story. There is one aspect however that has fallen short. ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith, like many commentators, has described the players’ strike as “unprecedented,” as if young athletes have never — outside, perhaps of the film Varsity Blues — banded together and refused to take the field. This is not actually true. It is worth knowing the history of rebel teams because it makes the actions of Grambling State’s players less of an outlier, less of a freak occurrence and more a part of a continuum, however sparse, of players saying that there are more important things in life than obeying authority and agreeing that the gob of spit in your face is indeed rain.

The first time you see players coming together in a way that garnered national attention, was in 1936. Another historically black college, Howard University in DC, saw players walk off their “job.” The team went on strike before a home game against Virginia Union because their school refused to provide them with food. When it came to any kind of pre- or post-game nutrition, the “student-athletes” were on their own. As one player said to Time magazine, “We were too hungry to get in there and battle those big country boys full of ham and kale.” That week, Howard students boycotted classes in solidarity with the players and marched down DC’s famous Georgia Avenue chanting, “Food! Food! Food! We want food!” with placards that read, “We Want Ham and Cabbage for the Team!”

The 1960s and 1970s also saw players repeatedly demand that they have a voice independent of their head coach. At the University of Washington, athletes won a study of racism in the athletic department after accusing a football trainer of making racial slurs and providing inadequate treatment for injuries.

Univ. of Washington newspaper from April 17, 1968. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

That May of 1968, Howard University again saw their athletes speak out. They threatened to quit teams en masse, unless Athletic Director Samuel Barnes was removed. They also wanted “better food, more medical attention, streamlined means of transportation, more equipment, better living conditions and a full-time sports information director.” Student assembly president Ewart Brown Jr., a member of the track team publicly burned his Howard varsity sweatshirt. As it went up in ashes, football player Harold Orr said, “This is what we think of the athletic program. [We need a] cremation of the old system.”

The cascade of protest continued. In February, African-American basketball players at Notre Dame’s basketball team threatened to quit unless they receive a public apology from students for booing when they were all in the Michigan State game at the same time, creating what at the time was the rare sight in South Bend of five African-American players at the same time.

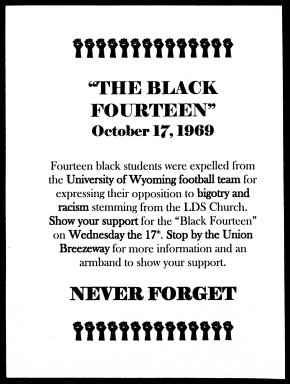

Call to wear black armbands to show support for the Black 14. Image: Irene Schubert Black 14 Collection at the Univ. of Wyoming.

But nowhere and at no time did athletes come together in anger and against the wishes of coaches and athletic directors than when it came to playing Brigham Young University. BYU was affiliated with the Mormon Church, which denied leadership positions to African-Americans, claiming that their dark skin was “the mark of the curse of Ham.” This would remain church policy until 1978. In October of 1968, the Wyoming football program dismissed fourteen players for wearing black armbands the evening before the team was scheduled to play BYU. They called themselves the Black 14 and unsuccessfully sued for $1.1 million in damages with the support of the NAACP. On October 25, in a game with San Jose State, the entire San Jose team wore black armbands to support the Black 14. (San Jose State was also the home of these guys, making it a place where protest and sports hit together like fist in glove.)

In November 1969, primarily because of controversy surrounding Brigham Young, Stanford University President Kenneth Pitzer announced that Stanford would honor what he called an athlete’s “right of conscience.” This “right” would allow the athlete to boycott a school or event that he or she deemed “personally repugnant.”

One of the great forgotten stories however, took place in Seattle in 1972. That year at the University of Washington, the team refused to come out after half-time unless their opposition to the war in Vietnam was read over the public address system. According to journalist Dean Paton, who worked for the Huskies Sports Information Office and was charged with delivering the team’s message to the public address announcer, the following words were heard throughout the stadium:

“Ladies and gentlemen, may we have your attention for a very important announcement: The football team at the University of Washington wishes to take this moment to express its concern over the present situation in Vietnam. Toward this end, the team will now delay the game for a couple of minutes.”

Dean Paton recalled to me, “As Wendell’s words echoed throughout the stadium, a loud symphony of boos arose from the seats on the stadium’s south side, where the alumni donors and wealthy season ticket holders sit. The boos were unremitting, and they grew as Wendell continued: ‘The players basically have one thing to say: they feel the war and the killing should be ended immediately. The team wishes you would take these few minutes to think about what has happened in the world this week and what consequences they may have. Thank you…. The game will now resume; the team thanks you for your patience.’”

Logo of All Players United logo. Learn more at the National College Players Association.

Today, as players wear All Players United on their clothes to say they are sick and tired of the status quo in college sports, Grambling State reminds us that as bad as the status quo is at mega-schools in the power conferences, it can also be far worse. It is awful for the haves. It is even worse for the have-nots, and that is why change is coming to college football. Fired coach Doug Williams, who had been staying out of the current conflict because his son D.J. Williams is the team’s starting quarterback, texted, “I’m proud of them boys. They took a stance.” The question is whether the NCAA, Bobby Jindal, the Obama administration and others will listen and stop treating HBCU’s like separate and unequal institutions. At all schools, the NCAA will also have to to stop using so called student-athletes like expendable pieces of equipment, people with arms and legs but without minds of their own. Whether they do or not, you can count on there being more stances to come.

By Dave Zirin. Reprinted with permission of the author. First published as “ESPN Is Wrong: Grambling State Isn’t the First College Team to Fight Back” on 10/21/13 at TheNation.com. Zirin is sports editor for The Nation, host of Edge of Sports, and co-author of The John Carlos Story and more.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn