Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery, by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank, examines what its authors view as “a shameful and well-kept secret” — the critical role played by the North in supporting and profiting from slavery, from colonial times until, and even after, the Civil War.

Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery, by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank, examines what its authors view as “a shameful and well-kept secret” — the critical role played by the North in supporting and profiting from slavery, from colonial times until, and even after, the Civil War.

The authors, all journalists for The Hartford Courant, argue that most Americans have learned only about slavery in the South. As a result, the authors argue, many Americans emerge from school believing that the North and its citizens watched innocently as the institution of slavery took root and thrived across the Mason-Dixon line, and finally decided to go to war to hold the nation together and ultimately end the evil institution on which the South depended.

As Complicity passionately and powerfully chronicles, that was not what actually happened. Slavery could not have become institutionalized in the South without the active participation of northerners. As the authors argue, their state of Connecticut, and the entire nation, were complicit. This complicity took many forms — ownership of people, promotion and funding of the trade in people and active involvement in it, support for fugitive slave laws, use of “science” to defend notions of white supremacy, and even the support for the ivory trade, with its disastrous impact on Africans — an impact that lasted well into the 20th century.

Complicity shows us the villains — the slave traders, the racists, the apologists, and the politicians. But it also teaches us about the heroes. Among them are Prudence Crandall, a Connecticut teacher who opened a school for black female students and, despite her arrest, continued fighting for her students’ right to an education, and Elijah Lovejoy, an abolitionist minister and newspaper owner who died protecting his printing press. We are given a new and more sympathetic portrayal of the radical abolitionist John Brown, who, next to slavery itself, was most infuriated at the apathy of Northerners.

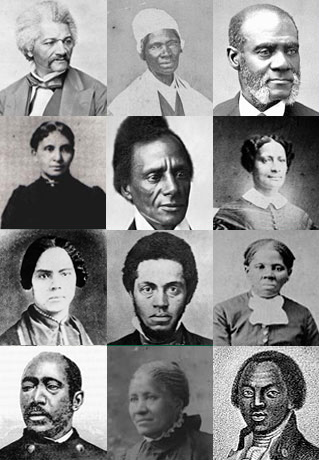

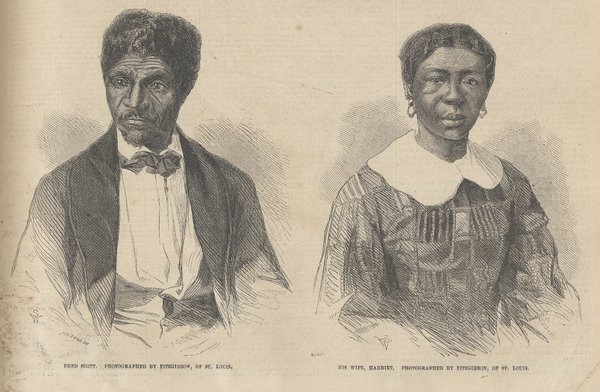

We learn that it is not always so easy to characterize the players in this real-life drama; there were abolitionists, for example, like George Read and Julius Pratt, who were pioneers in the antislavery movement yet made their fortunes in the ivory trade, where as many as two million Africans were brutalized. Most of all, enslaved people and formerly enslaved people share their voices in this book, as active participants in the struggle against oppression. We meet characters with whom most of us are unfamiliar, such as Venture Smith, whose narrative of his life as a slave survived and speaks to us, and Caesar Vaarck, a slave executed for his role in the New York City slave rebellion—the “Great Negro Plot” of 1741. During the course of the book, we are also reacquainted with figures we have met before: Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and Nat Turner.

The authors’ Afterword restates their purpose, one that the reader should keep in mind. By 1860 there were approximately 4 million people who were enslaved, valued at 3 billion dollars in the United States. They wanted to “set the record straight” and prove that even though the North went to war, in part, to end slavery, the Civil War “masked the economy and shared racism that bound the states together.”

Slavery was not a southern institution; it owed its existence to the nation, specifically the North. And the legacy of slavery is certainly still with us. In their conclusion, the authors quote Philip Graham, a former publisher of The Washington Post, who argued that journalism is all about giving a rough draft of history — a “draft that will never be completed about a world we can never understand.” Farrow, Lang, and Frank set out to change the original rough draft and instead offer to us a second.

One of Complicity’s greatest strengths is its reliance on archival information and research. The text is interspersed with a nearly limitless collection of statistics, photographs, maps, newspaper clippings, slave narratives, speeches, and letters. [Publisher’s description from intro to Teaching Guide.]

ISBN: 9780345467836 | Ballantine

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn