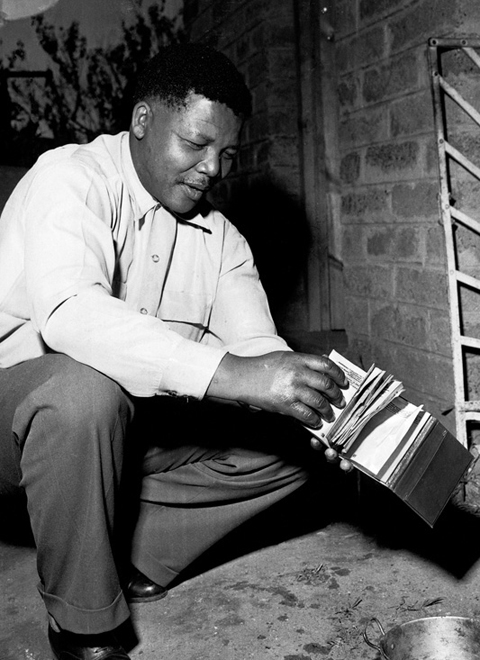

Even though it had been expected, I was jolted when I got the phone call with the news that after many long decades the defiant fire of resistance had gone out and Nelson Mandela had died. He was the only truly great public figure I’d ever covered, an authentic revolutionary who refused to cower in the face of the most malignant of evils.

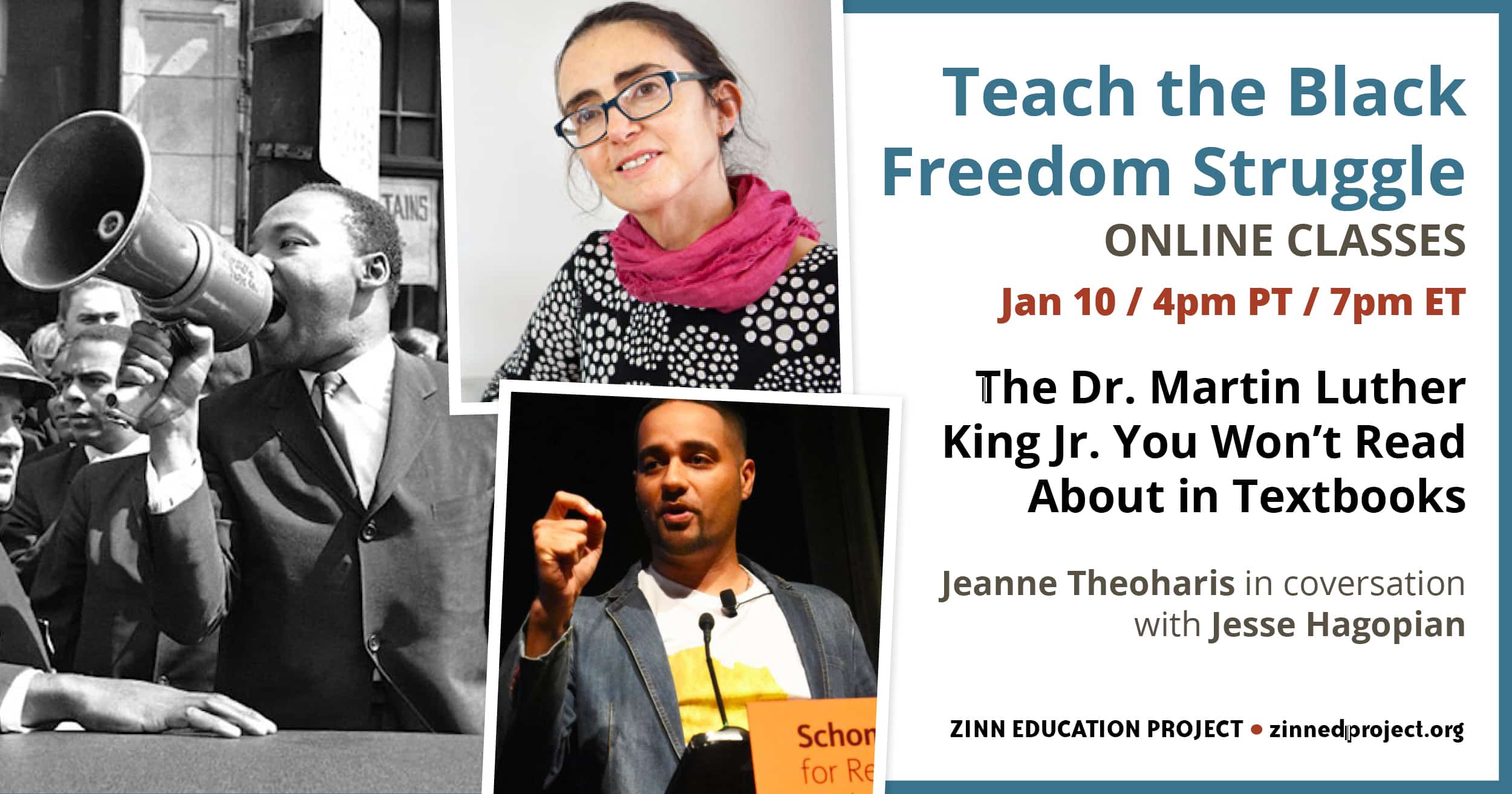

I knew that the tributes would be pouring in immediately from around the world, and I also knew that most of them would try to do to Mandela what has been done to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: turn him into a lovable, platitudinous cardboard character whose commitment to peace and willingness to embrace enemies could make everybody feel good. This practice is a deliberate misreading of history guaranteed to miss the point of the man.

Nelson Mandela and friends sing ‘Nikosi Sikelel I Afrika’ at the end of their trial for treason in South Africa.

The primary significance of Mandela and King was not their willingness to lock arms or hold hands with their enemies. It was their unshakable resolve to do whatever was necessary to bring those enemies to their knees. Their goal was nothing short of freeing their people from the murderous yoke of racial oppression. They were not the sweet, empty, inoffensive personalities of ad agencies or greeting cards or public service messages. Mandela and King were firebrands, liberators, truth-tellers — above all they were warriors. That they weren’t haters doesn’t for a moment minimize the fierceness of their militancy.

Unlike King, Mandela accepted violence as an essential tool in the struggle. He led the armed wing of the African National Congress, explaining: “Our mandate was to wage acts of violence against the state. . . . Our intention was to begin with what was least violent to individuals but most damaging to the state.” Ronald Reagan denounced him as a terrorist and Dick Cheney opposed his release from prison.

King was hounded by the FBI, repeatedly jailed, vilified by any number of establishment figures who despised his direct action tactics, and finally murdered. He was only 39 when he died. When King spoke out against the Vietnam war, characterizing the American government as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today,” the New York Times took him to task in an editorial headlined, “Dr. King’s Error.”

King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech is remembered mostly for its stirring evocation of a friction-less world in which blacks and whites get along wonderfully well and people are judged solely by “the content of their character.” What typically gets left out of mainstream reminiscences about the speech was King’s indictment of the real-world treatment of blacks in America. “America has given the Negro people a bad check,” said King, “a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.'” He warned the crowd of a quarter of a million people outside the Lincoln Memorial:

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. . . . And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights.

These were not warm and fuzzy individuals, fantasy figures for the personal edification of the clueless and the cynical. They were hard-core revolutionaries committed with every ounce of their being to the wholesale transformation of their societies. When giants like Mandela and King are stripped of their revolutionary essence and remade as sentimental stick figures to be gushed over by all and sundry, the atrocities that sparked their fury and led to their commitment can be overlooked, left safely behind, even imagined never to have occurred.

It’s a way for people to sidestep the everlasting shame of past atrocities and their own collusion in the widespread horrors of racism that are still with us.

© Jacobin Magazine. Reprinted with permission.

Bob Herbert, a distinguished senior fellow at Demos.org, was an op-ed columnist at The New York Times for 18 years. He has won numerous awards, including the Meyer Berger Award for coverage of New York City, the American Society of Newspaper Editors award for distinguished newspaper writing, the David Nyhan Prize from the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University for excellence in political reporting, and the Ridenhour Courage Prize for the “fearless articulation of unpopular truths.” Bob Herbert was the featured speaker at the 2011 Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture Series.

Bob Herbert, a distinguished senior fellow at Demos.org, was an op-ed columnist at The New York Times for 18 years. He has won numerous awards, including the Meyer Berger Award for coverage of New York City, the American Society of Newspaper Editors award for distinguished newspaper writing, the David Nyhan Prize from the Shorenstein Center at Harvard University for excellence in political reporting, and the Ridenhour Courage Prize for the “fearless articulation of unpopular truths.” Bob Herbert was the featured speaker at the 2011 Howard Zinn Memorial Lecture Series.

I’m not so sure … I haven’t heard this “cardboard” characterization. I’ve read and watched news reports about how tough Mandela could be on enemy and family alike. (e.g., BBC interviews with family) Also read about his compromises with the likes of Mugabe & Gaddafi, who supported him while he was in prison.

Mr. Hebert’s references to the previously ignored beginning of the I Have A Dream speech are on point, and suggest for teachers a great way to globalize their curriculum by bringing in Mandela and his speeches when we talk about Dr. King. There is some irony in the fact that as MLK was receiving his Nobel, Nelson Mandela was being issued a life term.

You’re right.